A new bird has been found on Bear Island

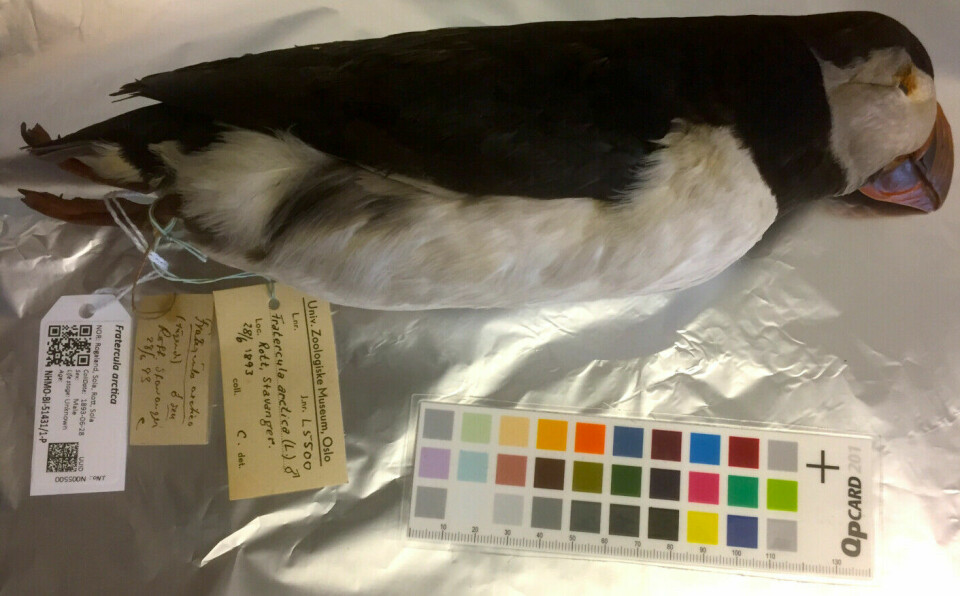

Modern DNA technology allows biologists to now peer into the genes of historical specimens that are over a century old at the Natural History Museum in Oslo and other museums. Through this method, the researchers made an unusual discovery in their lab.

“Old animals in museums have gained a whole new value,” Sanne Boessenkool enthusiastically tells sciencenorway.no.

The biologist at the University of Oslo and her colleagues have now examined all the genes – the entire genome – of all three subspecies of puffins.

They have also performed similar analyses on puffins that are over a century old and housed in museums.

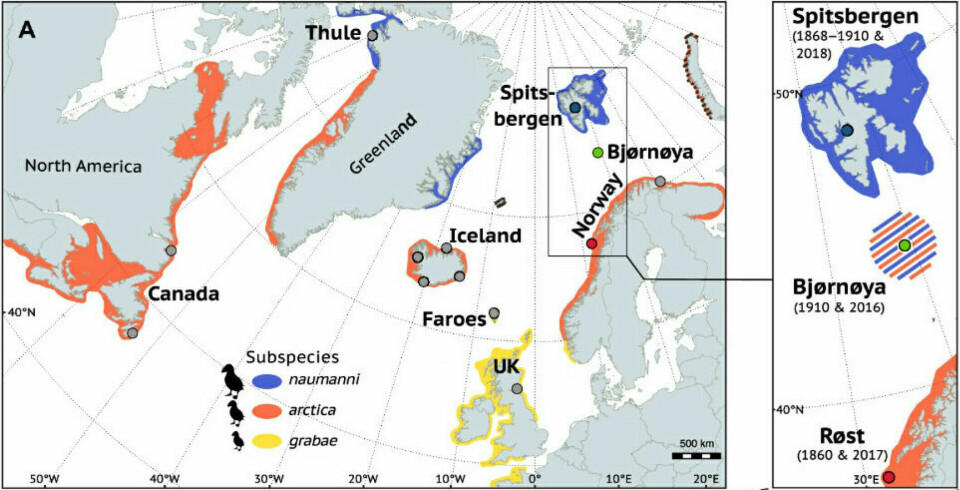

In Norway, researchers have examined birds from colonies on the islands of Røst off Lofoten, Svalbard, and Bear Island.

The study was completed last week.

“It was on Bear Island that we discovered that something very special has happened,” Boessenkool says.

Most intense global warming

No other place in the world has experienced such intense climate warming as Svalbard and Bear Island. Since 1991, the temperature in Svalbard has increased seven times as much as the average temperature increase on Earth.

What does this do to animals and biodiversity?

Researchers studying puffins could be the first to uncover how such factors can lead to rapid changes in animals.

Three kinds of puffins

If we go really far back in time, there was only one puffin.

Then – 100,000 years ago – a development began, where we eventually got three quite different subspecies of puffin.

- In Svalbard and North Greenland, the larger subspecies naumanni reside.

- Along the coast of Norway, in Iceland, and South Greenland we find the smaller bird arctica (which, despite its name, actually lives further south).

- On the British Isles, the subspecies grabae lives, which is the smallest of all the puffins.

Puffins in museums

Have you been to a natural history museum and seen mounted animals?

Then you've probably also seen some old stuffed puffins. Few other birds have such a striking appearance as the puffin.

Another name for it is sea parrot.

The puffin is one of Norway's most common seabird species and important for the ecosystems in the sea off our coast.

“But we knew nothing about the puffin’s genetic variation before we started this study,” Boessenkool says.

A new bird on Bear Island

120 years ago – around the turn of the last century – there were still three completely separate subspecies of puffins in Europe.

The biologists at the University of Oslo see this when they examine all the genes of such old museum birds.

Researchers can confirm that the different subspecies of puffin still live separately, as they may have done for 100,000 years. The subspecies have not hybridised – had offspring with each other.

“The exception is Bear Island,” Boessenkool says.

Bear Island is located in the Barents Sea between Finnmark and Svalbard.

“Here we clearly see that something different has happened,” she says. “And the strange thing is that it happened so quickly.”

When the researchers examined the entire genome (all the genes) of puffins on Bear Island, they discovered that all the birds living there today are the result of hybridisation.

It is the two subspecies naumanni from Svalbard and arctica that live along the coast of Norway, that have combined to form a new bird.

“120 years ago, it was only arctica, the southern variant, that lived on Bear Island. We can see this from the museum birds we have examined that are from Bear Island,” she says.

“Now all the birds on Bear Island have become a new hybrid species.”

Is climate change the cause?

The research team is highly astonished that such a significant transformation could occur in merely a century.

A hundred years is actually not a long time to change genes in an animal.

“The other thing that surprises us is that it’s the naumanni that has moved southward from Svalbard,” she says. “We biologists often think that as the climate warms, all animals and plants move northward. However, in this case, an animal has moved in the opposite direction, southward, resulting in a new hybrid bird.”

If the warming of the Arctic climate is behind this development, it shows us that biological changes in a new climate can be difficult to predict, Boessenkool notes.

Among the first in the world

The researchers behind this new study are among the first in the world to examine the entire genome of seabirds, in order to be able to concretely demonstrate how biological diversity is changing.

Boessenkool informs sciencenorway.no that the techniques available for this type of research have rapidly advanced.

“In addition, we are increasingly understanding more and more of the information we can extract from animal DNA,” she says.

Boessenkool has specialised in extracting DNA from animals that died a long time ago, whether they are 100 or 10,000 years old.

“It opens an incredibly exciting window into the past, to be able to peek into the genes of animals that died a long time ago,” she says.

How endangered is the seabird?

In Oslo, Stockholm, and New York, there are old mounted puffins that researchers can extract DNA from for studies like this.

Such birds are often over 100 years old.

sciencenorway.no has previously reported on how puffin chicks are now dying due to a lack of food.

Especially on Røst at the outermost part of Lofoten, the decline has been strong. From 1.4 million breeding pairs 40 years ago to about 250,000 pairs today.

On Røst, NINA researcher Tycho Anker-Nilssen had to conclude a few years ago that there were no birds under 16 years old.

The puffins in the breeding colonies on Røst had then not been able to produce chicks for many years. On the Norwegian mainland, the arctica puffin is now red-listed as a highly endangered species (link in Norwegian).

But now in 2023, Anker-Nilssen informs sciencenorway.no that this was the first year since 2006 that the puffins on Røst have had reasonably good breeding success.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

References:

Kersten et al. Complex population structure of the Atlantic puffin revealed by whole genome analyses, Communications Biology, 2021.

Kersten et al. Hybridization of Atlantic puffins in the Arctic coincides with 20th-century climate change, Science Advances, 2023.