The rodents are back: Surprising amounts of mice in Eastern Norway

The phenomenon of rodent population explosions had stopped appearing in Norwegian nature. Until around the year 2000, when they for some reason returned. This summer, enormous amounts of mice have taken over Eastern Norway.

This spring, there were hardly any mice around in Eastern Norway. Over the summer however, heaps of them were born.

For the rest of the country, a peak year for the little rodents may come next year.

For a long time, so called rodent years, more commonly known in Norway as "mice years" or "lemming years" - years when populations of these rodents explode - were not observed in Norwegian nature. But around the beginning of the new millennium they returned.

Now they are here in full force.

Numbers shot up

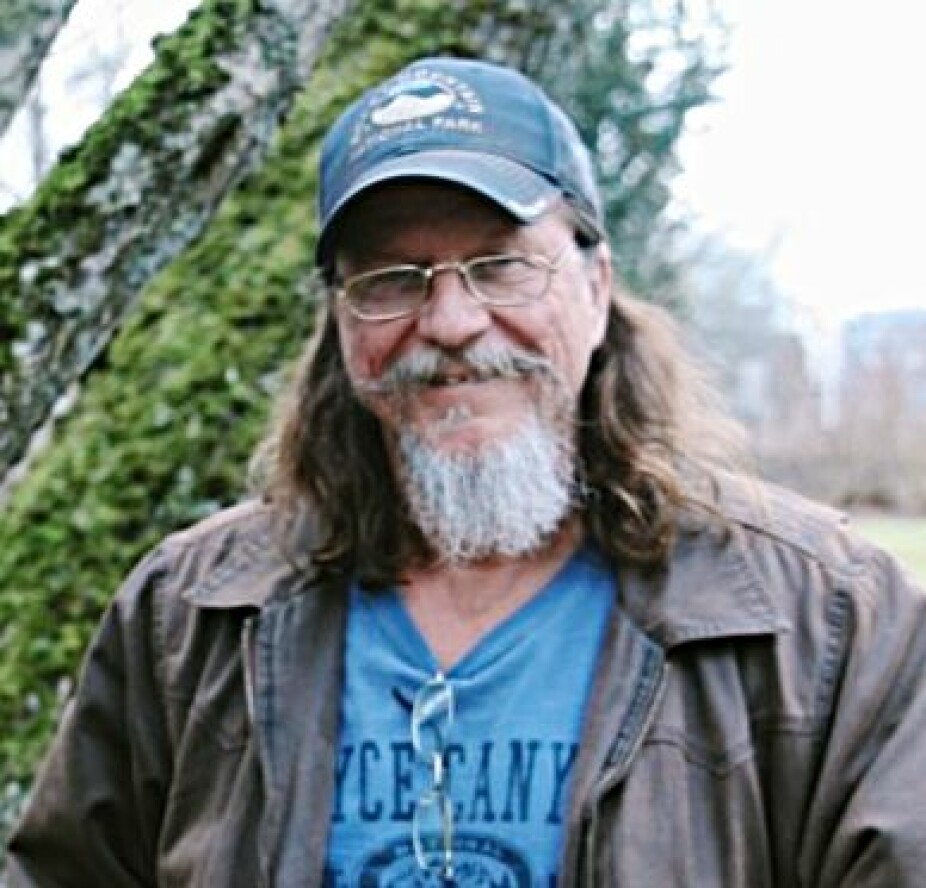

Jørund Rolstad is a researcher with the Norwegian Institute of Bioeconomy Research (NIBIO). He monitors the development of mice and voles every year, and advices Norwegians with houses and cabins in Eastern Norway to pay extra attention in the coming months.

He is surprised at how quickly the numbers shot up.

When Rolstad counted mice and voles in the forest this spring, he barely found any. But then during the summer, the numbers exploded.

There are especially many bank voles, according to Rolstad. And quite a few wood mice. The latter eats seeds and has probably enjoyed the fact that the trees have had plenty of spruce cones this year.

Both of them may try and enter houses and cabins.

“If we get a lot of snow this winter, which the mice can hide under, then we may get even more of them next year”, says Rolstad.

Rolf Anker Ims does research on rodents at UiT The Arctic University of Norway. He believes Norway may get a peak year for lemmings and field vole in 2021 or 2022.

These are both rodents with regular cycles of population peak years some time between every third and fifth year.

The rodents are back

It was only after the turn of the most recent century that the explosive "rodent years" came back in full force in Norwegian nature. Before this they had been gone for many years.

The year 2014 was a mice year unlike any people and researchers had experienced previously.

Nature was packed with bank voles and field voles. Hikers in the forest also spotted lots of odd-looking black and blue-ish mice-looking creatures. They were found dead on tracks and in streams.

These were wood lemmings.

“Eight or even ten years may pass between every time we see a lot of wood lemmings”, says Jørund Rolstad.

Predators like foxes are probably not very interested in eating this moss-eating rodent. Maybe it doesn’t taste very good. But foxes and other predators are happy to kill the wood lemmings.

This is why we all of a sudden, with many years in between, witness several of these blue-ish rodents dead all over the forest.

From hundreds to barely any

During the extreme mouse year of 2014, mice were literally crawling all over the forest. Per every 1000 square meters of forest floor in southern Norway, between 70-100 mice were counted.

When the rodents now are back, the nature researchers see how important they are for the variations in Norwegian nature. When there are lots of rodents – birds of prey, owls, foxes, vipers, stoats and weasels can feast on the abundance of food.

This in turn enables them to reproduce profusely.

Tougher for the fox and owl

And when there are a lot of mice and lemmings available, predators leave the hare cubs more alone. So we get more hares.

But when the rodent population collapses in the subsequent year, squirrels, little birds and hare cubs pay the price.

Eventually the predators starve and fail to reproduce. Both foxes, owls and others who live off mice have a tough time when the rodents are gone.

So why did this pulse of nature start to beat again in Norway 20 years ago? The researchers don’t know for sure.

But they do have some hypotheses.

Blueberries and snow

Could blueberries be the explanation?

In short – when there are a lot of blueberries in a given year, these blueberries spend less energy on creating a type of toxin that plants make in order not to be eaten, a poison that sits in their leaves.

If the blueberriebushes are less poisonous, this means that Norway’s most common vole, the bank vole, can feast on them.

Another hypothesis is about the snow cover during winter. If there is a lot of snow, the mice can live protected under it. Less snow and cold temperatures create a rougher climate for the mice to survive in.

Finally, a hypothesis about those who eat mice. Stoats and weasels eat enormous amounts of mice. If there are fewer mice, these weasels reproduce a lot less, which again gives wood mice, bank vole and field vole a chance to live to reproduce more. And so it goes, back and forth, with a few years in between.

“Most likely, several factors interact when we get rodent years”, says Jørund Rolstad from NIBIO.

Rodent years appear on average every fourth year.

Rolf Anker Ims at UiT The Arctic University of Norway believes that researchers now have a fairly good understanding of what factors may give regular rodent years, underscoring however the word may.

“Both interactions with plants for food and natural enemies like predators and diseases are probable candidates. What is yet to be discovered is the actual importance of these different processes and their interactions”, he says.

Translated by: Ida Irene Bergstrøm

———