Clumsy clown of the seabed

The spiny lumpsucker is too sluggish to avert the slow hand of a diver, yet it manages to catch some of the most important swimmers in the Arctic Ocean.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Have you ever heard of the spiny lumpsucker? No? You’re not alone.

Marine biologists working in the north Atlantic and Arctic waters might be expected to have heard of them, but until recently they knew so little that they confused males and females as two different species.

Not an impressive swimmer

“The Atlantic spiny lumpsucker is a fairly common fish around Svalbard,” says Jørgen Berge.

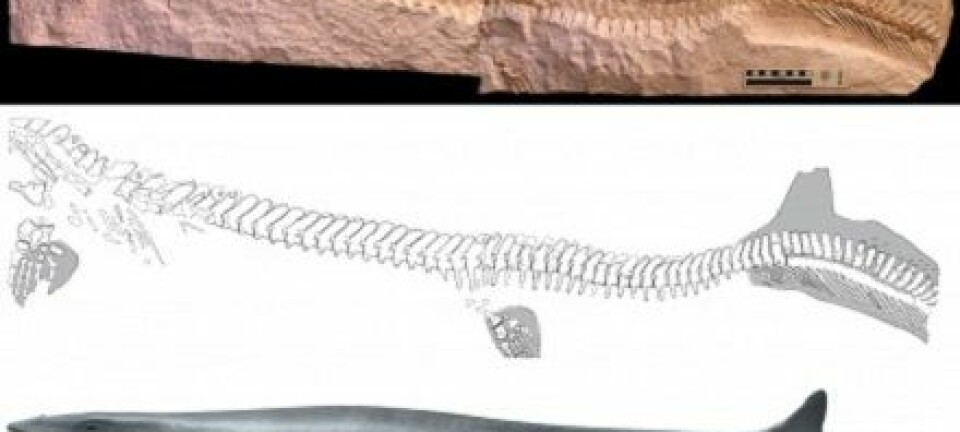

Berge is a University of Tromsø professor who spends much of his time in Norway’s Svalbard archipelago, above or beneath the Arctic Ocean waves. He has encountered the 10-12 cm fish plenty of times.

“It’s an extremely poor swimmer, mostly keeping stationary in the kelp beds. You can swim down to it and cup it in your hand, and it just sits there. If it does try to swim away all you need to do is move your hand a little and you have it again,” explains Berge.

Slow, but sated

You might wonder how such a sedentary creature gets enough to eat.

“Despite being so sluggish and poorly camouflaged, it eats its fill of zooplankton,” says Jørgen Berge.

The zooplankton Themisto libellula is an amphipod which is pelagic – meaning it swims freely in ocean waters.

“It migrates up and down daily. At night it ascends to the upper layers of ocean, hidden by darkness. Then it hides down in the depths during the day to avoid being eaten,” Berge says.

He describes this daily migration from the surface to the depths as the largest synchronised movement of biomass on the planet.

Waiting to be served

When he and colleagues examined 250 spiny lumpsuckers they found that more than 90 percent of the fish had eaten nothing but this kind of animal plankton.

He has subsequently caught and examined more of the fish with the same result.

“The only way the spiny lumpsucker can do this is to wait on the ocean bed for the food to descend to it,” concludes Berge.

The importance of amphipods

The researchers have not only discovered something new about a rather obscure and somewhat clownish-looking fish. They have learned more about Themisto libellula.

“This is a key species in the Arctic ecosysytem and a vital food source for polar cod, seabirds and seals. Now we know more about how it migrates and that it swims all the way to the bottom during the day,” explains Berge.

The only previous indication of this was a report from a Russian submersible vessel on a mission to film a sunken submarine. The resulting video showed a swarm of Themisto libellula all the way down on the sea bottom.

The repeated discovery of these tiny creatures in the stomachs of spiny lumpsuckers shows that sinking to these depths is part of their modus operandi.

Biological CO2 pump

The information gained from checking out the stomach contents of a weird little fish don’t stop there.

Scientists now understand how the migration of zooplankton from the surface to the bottom of the sea acts as an enormous biological carbon pump to the seabed.

Themisto libellula feasts in the upper layers of the sea at night – mainly consuming the marine copepod Calanus finmarchicus. Thermisto then swims to the bottom to digest its nocturnal snack – unless it happens to swim straight into the mouth of the spiny lumpsucker.

“In this way they carry organically bound carbon down into the sea, where it is released through respiration and digestion as carbon dioxide.”

“In other words it’s an important contributor to drawing the greenhouse gas out of the atmosphere and down to the bottom of the ocean,” says Berge.

-----------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling