This sealed chamber contains some of Norway's most fragile and magnificent treasures

Moving the Viking sleds about a hundred metres to the new Museum of the Viking Age is not for the faint of heart. They can move only minutely, or things will go wrong.

The chamber is always dark – like a closed tomb. Except when someone peeks in.

“This is one of the most fragile items we have at the Museum of Cultural History,” says conservator David Hauer.

Three sleds are lined up inside the chamber. They are widely regarded as some of the most exquisite woodcarving work known in Norway, he adds.

The secure room has been set up in the old museum shop at the Viking Ship Museum on Bygdøy. There, the sleds are stored as far away from the ongoing outdoor construction site as possible.

"The most demanding work we do"

The sleds are on a special, cushioned platform to isolate them from the construction site vibrations. The room is dark and the humidity is precisely controlled to preserve the sleds as much as possible.

They will soon be moved again.

“This is the most demanding work we do,” says Hauer.

Hauer has spent years planning this move. You can read more about the move of the Oseberg Ship and the other Viking ships here.

But moving the sleds is an even more challenging task. Over the next year, they will be lifted and moved to carry out their final sled ride, from the secure room and into the new Museum of the Viking Age.

Stored in a basement during the war

The sleds have lived a rich life after lying in the burial mound with the Oseberg Ship for over a thousand years.

Hauer explains that they were first displayed at the Historical Museum in Oslo. But during World War II, they were placed in the museum basement for protection.

They remained there for over a decade before being moved to the museum on Bygdøy. They were exhibited in 1957.

Underneath, the sleds are supported by a network of iron rods and supports.

That is because they are extremely fragile, and they are assembled in a way that would never be done today, says Hauer.

The result is that the sleds can barely tolerate any movement at all during the relocation.

Hauer and his team have calculated that the sleds cannot be twisted, stretched, or compressed more than 0.2 millimetres before something might go wrong and damage could occur.

“If we stay within that limit, everything will be fine,” he says.

A scientific description of the techniques used to support the sleds can be found in this study from 2024.

The sleds are monitored by a network of sensors and are covered with mesh inside the chamber that can catch fragments in case anything falls off.

Thosee pieces can then be put back into place, says Hauer.

But why are the sleds so fragile?

Salt clumps held together by rusty nails

The Oseberg find was extremely well preserved because the grave was sealed, and many of the wooden objects inside were submerged in water.

That’s why we have Viking Age objects that have survived over a thousand years in the burial mound. The artefacts include a magnificent and almost completely intact bucket, beautifully carved animal heads, and the original coiled serpent head from the bow – which has never been exhibited before.

The Viking ship itself was in surprisingly good condition, but many of the wooden objects had to be treated after they were found to prevent them from disintegrating.

The three sleds were shattered into thousands of pieces when they were discovered in the grave. The ship was also partially destroyed.

Each sled consists of nearly a thousand fragments that were assembled in the years following the excavation. They are made from different types of wood, according to the descriptions in the book The Oseberg Find, Volume 2, from 1928.

“I’ve looked closely at the old photos, and the job they did to puzzle it back together was incredible," says Hauer.

These are magnificent objects, but they were built as functioning sleds, he explains.

New wood was added where the runners had worn down, which shows that they were used.

“Sleds like these were used both in summer and winter, and they were pulled over grass," he says.

Today, the sleds can no longer support their own weight.

Salt baths, clumps, and wet school chalk

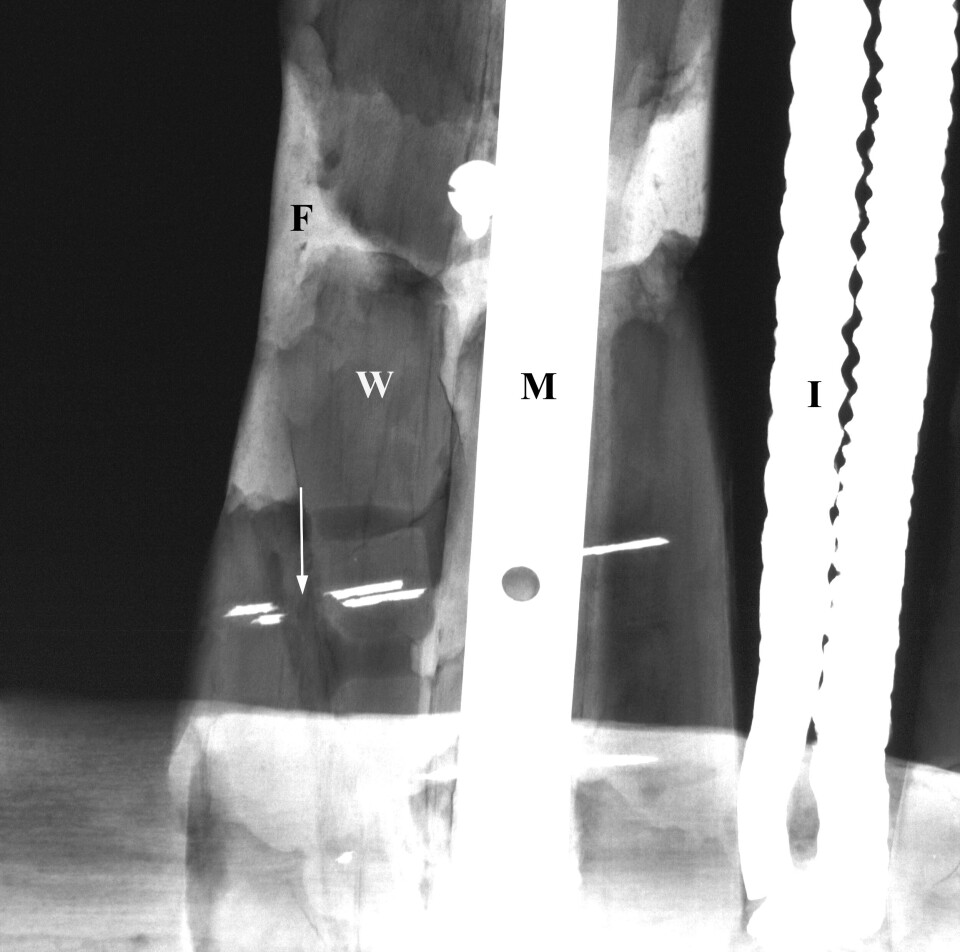

X-rays show that iron nails, rivets, brass fittings, and glue hold the sleds together. There are also serious issues with parts of the metal.

And the wooden fragments are no longer wood as we know it.

Both the sled fragments and other items have been preserved using an alum treatment. This is a process in which the wood is soaked in very hot salt baths to saturate it with salt.

The salt fills the empty spaces inside the wood. When the water evaporates, the salt crystals help the wood retain its shape, but it becomes something quite different from ordinary wood.

“It’s almost like salt clumps,” says Hauer.

This has made the sleds much heavier than they originally were. The heavy salt-filled wood fragments are held together by over a hundred year old rivets, nails, fittings, and glue.

“It shatters like glass, but it isn’t glass at all,” he says.

Hauer describes the consistency as wet school chalk.

At the same time, this salt solution did not fully penetrate the wood, so many pieces have completely crumbled cores.

No one knows exactly what condition each individual fragment is in.

Without the treatment, there would be no sleds today

This treatment creates major issues today, although Hauer believes it was the best they could do after the burial mound was opened in 1904.

“Without that treatment, we wouldn't have these artefacts today. It was the best method they had at the time,” he says.

The problem is that certain types of waterlogged wood crumble into dust when they dry. So it had to be treated in some way.

But this had several unintended consequences.

Dust and sulphuric acid

Sulphuric acid formed in the alum bath.

This acid continued to seep into the wood, which just continued to deteriorate. No one knew that at the time, says Susan Braovac.

She is a conservator at the Museum of Cultural History and specialises in the preservation of wood. She has long worked on how these wooden objects can best be preserved for the future.

“And the degradation continues today. It's a self-reinforcing process,” she says.

The sulphuric acid makes everything worse by creating a highly acidic chemical environment inside the wood. She explains that the acid also attacks the iron that holds the fragments together, which weakens the sleds even more.

The condition of the sleds is so precarious that Braovac is now leading a project to explore how they can be preserved in the future, after they have been moved to their new display cases in the new part of the Museum of the Viking Age.

She often gets asked how long these sleds will last, and how much time is left. But for now, there's no clear answer.

“We’ve seen that they’ve lasted a hundred years, and we’ve seen what’s happened to them,” she says.

The researchers are exploring multiple methods. Which one will work best is still uncertain. The project is expected to run for several more years, according to the Museum of Cultural History.

But first, the sleds have to be moved from their secure chamber.

Moved during the war – and now to be moved again

David Hauer explains that the relocation will happen in several phases.

The sleds have already been moved on rails from their previous location in the old museum into the specially built secure chamber where they are now.

They will remain there until the spring of 2026, before being moved again using a custom-designed jack-and-crane system.

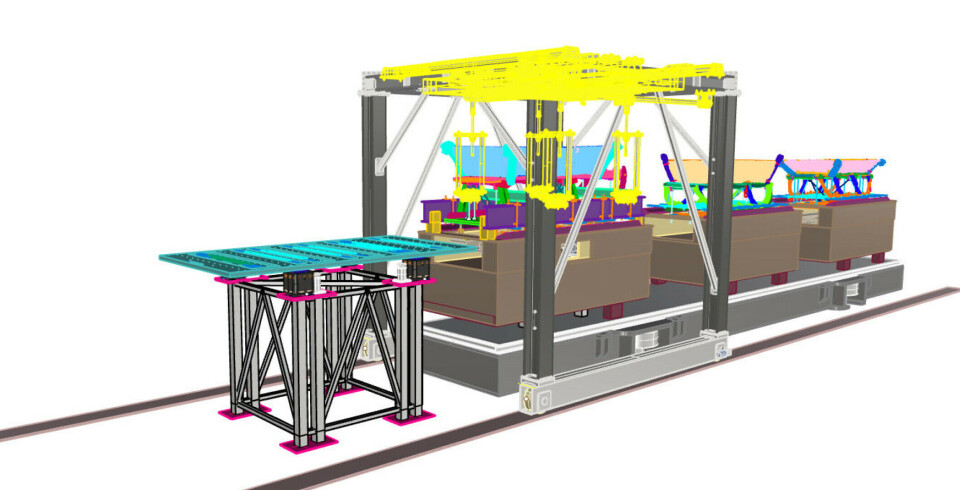

Each sled will be lifted individually with a specially built crane, as shown in the illustration below. After that, the sleds will be rolled on a rail system into their new display cases next to the Oseberg Ship.

But before that, conservators must ensure the sleds are reinforced as much as possible.

This involves lifting each sled, one at a time, on its own wooden platform using many small jacks. The sleds still rest on the original wooden plates they were reconstructed on in the early 1900s, following the opening of the Oseberg burial mound.

Each of these wooden plates will be secured to a much thicker and stiffer steel plate.

“That means the entire sled has to be lifted 160 millimetres,” says Hauer.

All future lifting operations will be done using this steel plate, to minimise any movement of the sleds.

Most viewed

Experts must constantly assess and account for the amount of vibration caused by the lifting systems themselves.

And everything must happen so slowly and gently that it does not exceed the 0.2 millimetre deformation limit.

The first move, where the sleds will be mounted onto steel plates, will take place in late August or early September, according to Hauer.

———

Translated by Ingrid P. Nuse

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

Related content:

Subscribe to our newsletter

The latest news from Science Norway, sent twice a week and completely free.