Before glass windows, people had windows made from cow stomachs

What did people do to bring daylight into their homes before glass windows became common in the 18th century?

“Glass windows were very uncommon in the living rooms and homes of the average Norwegian,” says Geir Thomas Risåsen, a conservator at the Norsk Folkemuseum (in Norwegian).

It started with skylights.

The fact that the skylight came before glass panes may surprise some.

At the same time, it makes sense.

From a cow stomach skylight to window panes

People lived in small huts with holes in the roof, called ljore. The hole was to allow the smoke from the fire in the hearth in the middle of the floor to escape. The hole had to be able to be sealed, for example, during cold winter nights, when the fire went out.

That's when they used cow stomachs. Or a pig's stomach. It was called sjåskinn when it was used as a window.

A hole in the roof provided valuable light to an otherwise rather dark timber building. The sjågrind with a sjåskinn, or a frame covered with the stretched animal stomach, allowed light to come into the living room even when the smoke hole was blocked. It was a prized alternative to a wooden plate.

The sjåskinn they have at the Maihaugen museum in Lillehammer today was made by the tanner Frode Jansson in 2022. It’s made from a cow stomach.

A local newspaper called Gudbrandsdølen Dagningen wrote about the new sjåskinn when it was first introduced. According to the newspaper, the public remarked that the skin gave enough light to allow women to do needlework in an otherwise dark room in a wooden building.

In addition to the sjågrinda, these structures had small openings in their timber walls that could be closed with a wooden block. That allowed inhabitants to regulate the draft when the hearth was fired, or to peer outside.

Complicated workshops

Glass panes first appeared in churches from the 12th century. The windows were small to begin with. Norwegian cathedrals, on the other hand, were built with large leaded glass windows. They were produced in Norway by local workshops.

The cathedrals were built in the country’s episcopal dioceses, which were important centres of power in the Middle Ages. There were large, local builder’s huts next to the cathedrals, Risåsen said.

Craftsmen of all kinds who were needed to build a cathedral had places in the builders' hut. The glassmaker's workshop was a small but important part of the overall effort.

Several hundred years would pass before windows could be found in ordinary homes.

“The great revolution for most people comes from the 17th century onwards,” Risåsen said.

Then something important happened to houses.

Curtains and shutters

“With the arrival of the fireplace from the middle of the 17th century, building customs changed,” Risåsen said.

The opening in the roof disappeared and was replaced by a pipe that allowed the smoke to escape from the house. The window became a new element.

“To begin with, they were small, because glass was expensive,” Risåsen said.

City dwellers put shutters in front of their windows to shut out the world when evening came.

“From the end of the 17th century onwards, curtains appeared. They had a multi-part function,” the conservator said.

“They were decorative, and they protected rooms from drafts and could be drawn closed when the evening came. This was important in an urban setting where the houses were close together,” Risåsen said.

Drafts were still a problem. This was partly solved by something called a varevindu, which came to Norway in the late 19th century. This is an internal glassed window frame that transforms a single window into a window with two layers.

“In Nordic countries with a severe winter, this was important,” says Risåsen.

Easier to wash windows

These windows were useful until the second half of the 20th century. By this time, more women had entered the workforce, and the disadvantages of the windows became more apparent. They were complicated and time-consuming to wash.

People wanted a window that both kept the heat in and was easy to clean. This was quickly developed.

Risåsen's parents built their first villa in 1957. It had the old-style double windows.

Six years later they built their next villa. It had what were initially called ‘housewife windows’, which were top-swing windows, as they were called a few decades later.

With only two sides to wash and the option to flip the outside of the window in, it was possible to wash the new windows in half the time.

Status symbol

“Windows have been both a status symbol, and a luxury – a way of showing your social position and status. The bigger and more windows, the better,” Risåsen said.

Royals and nobles of course had valuable import goods long before regular folk. Examples can be found at Akershus Fortress, Bergenhus Fortress or the Archbishop’s Palace in Trondheim.

“The development of the window is connected with the development of building customs and economic development in general,” Risåsen said.

Most viewed

Best windows on the most important side of the house

Risåsen helped in the restoration of the Eidsvoll building, an effort that lasted from 2007 to 2015.

The building was originally built in the 1770s. It was modernized from the 19th century onwards. The businessman Carsten Anker owned the building at the time. He began to replace the small window panes with large, modern windows.

He could afford to replace the windows on the garden side, but not on the rest of the house. Glass was too expensive, Risåsen said.

The same can be seen in houses in Copenhagen that were built after the great city fire in 1795.

“The houses that were rebuilt have large, modern empire windows facing the street, but they saved money on the other side. There, the windows have small panes,” Risåsen said.

Good value even when used

There’s also evidence of the high price of glass at Maihaugen.

“Glass panes held their value, even if they were not brand new,” Kjell Marius Mathisen told sciencenorway.no. Mathiesen is a conservator and architect and head of the cultural history department at the Lillehammer Museum Foundation (in Norwegian).

Glass clearly had its place on the second-hand market as well. The house from the Ødegårdsstuen homestead in Fåberg (in Norwegian) testifies to this.

“We know that the building was built in 1861, but the windows are clearly from the 18th century. They probably got hold of some old windows from a large farm, perhaps as much as 90 years later,” says Mathisen.

At Aulestad, which was a large farm and the home of the Nobel laureate Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, the window glass was also reused.

The main house was assembled around 1814 from two 18th century houses, Mathisen said. Both timber and glass from the 18th century were reused.

Norwegian window glass from 1755

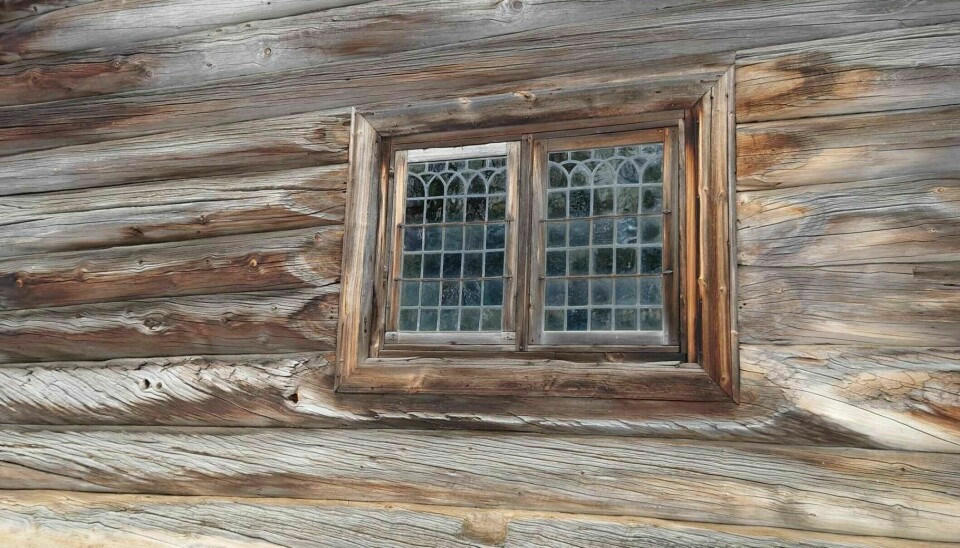

The oldest example of window glass at Maihaugen can be found in the Per Gynt loft (in Norwegian), built around 1620.

The panes of glass are small, and the frame was made of lead. The loft is the exception rather than the rule, says Mathisen.

In the book Maihaugen – nøkkelen til friluftsmuseet (Maihaugen - the key to the open-air museum) from 2005, the authors, including Mathisen, wrote that window glass only became common in the countryside after Norway got its first glass factory.

This was Hurdals Glassverk, established in 1755.

The glass factory at Hurdal produced exclusive crown glass. It wasn't for everyone.

It wasn't until 11 years later that glass became more affordable, when Biri Glassverk started producing so-called table glass.

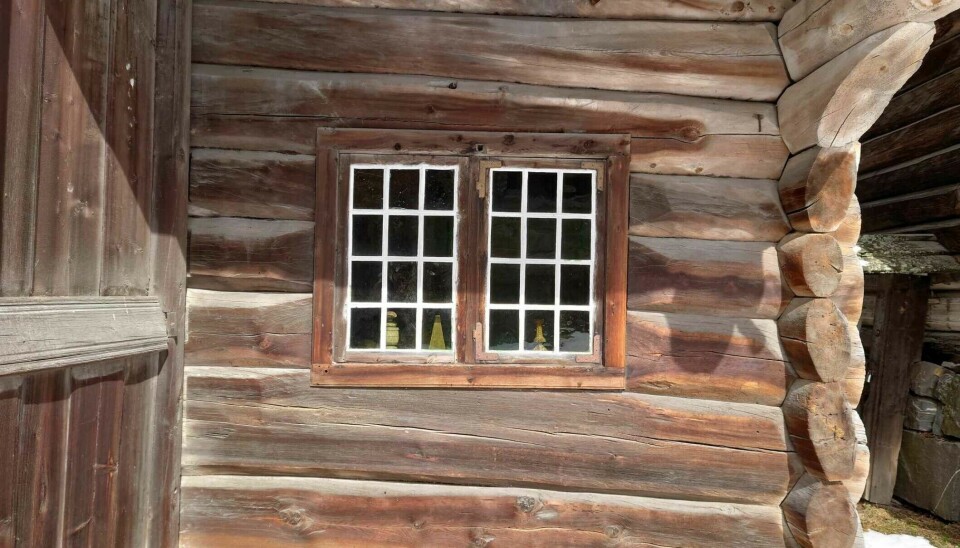

Towards the end of the 18th century, leaded glass went out of fashion, and window panes became larger. The lead was replaced by wooden bars.

Glass panes get bigger

One example is particularly visible at Maihaugen, on the large Bjørnstad farm. The entire farnyard is at Maihaugen.

“They built a house at Bjørnstad in 1777, which has much smaller panes of glass than the one that was built ten years later in 1787. It is clear that something was happening there,” Mathisen said.

It seems that access to large, fine glass had improved over a short period.

“If you had poorer finances, you managed with smaller windows,” Mathisen said.

Had to cool down for several days

Crown glass was first and foremost high quality glass. It was produced by blowing molten glass into a sphere, which was then attached to an iron rod and released from the blow pipe, the authors explain in the book.

There was an opening from where the blow pipe had been, and the glass ball was kept warm and rotated at high speed. The melted glass ball was thus flattened into a large glass disc.

The glass disc was still attached to the iron rod as it began to harden. Once the glass was hardened, it was divided into suitable, square window panes.

Table glass was cheaper, and preferably had a green tint.

Why are there uneven glass panes on some old houses?

Table glass was made when the glassblower created a large cylinder.

The bottom and top of the cylinder were cut off, and the cylinder was opened lengthwise and thus became a large surface as it was stretched out on a hot stone slab. The stone slab meant that the glass was often uneven.

After several days of cooling, the table glass could be divided into finished glass panes.

If you’ve noticed very uneven panes of glass on old houses, they are made of crown glass, but are cosmetic seconds.

“Where you attach the iron rod, the glass will be a bit lumpy. You could get this glass more cheaply, and it let in perfectly acceptable light — but you couldn't see out because the panes contained a lot of crumpled, bulky glass,” Mathisen said.

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no