Were people shorter before?

If you travel a few hundred years back in time, you will see that the beds look shorter, and the doors are very low. Why is that?

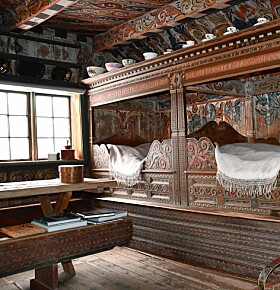

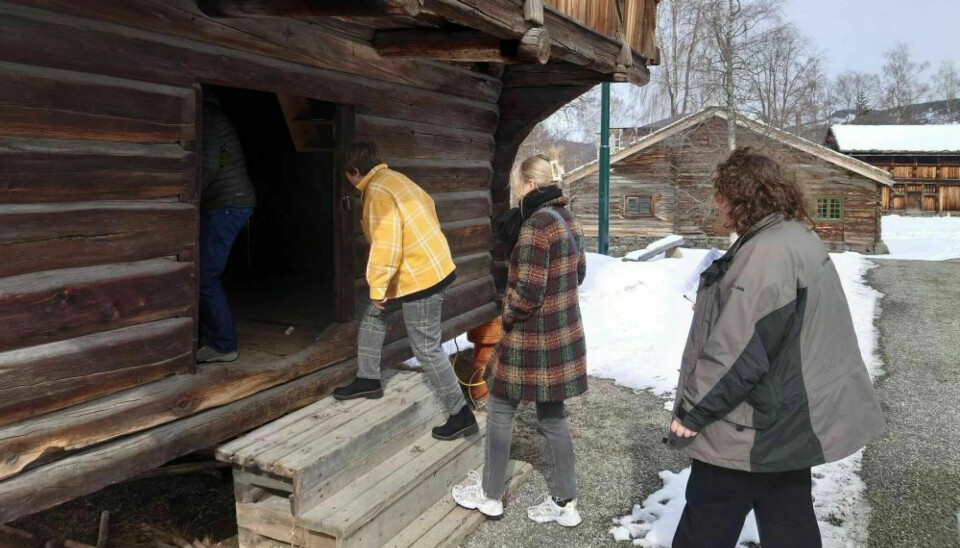

Perhaps you have been to a museum where you have seen short beds and have had to stoop through low doors.

But inside, there is ample height under the ceiling and plenty of space for several people in the bed.

What's the deal? Were people shorter before?

We have grown taller

There are several answers here.

First of all: Yes! People were shorter before.

According to Statistics Norway, men have become nearly 10 centimetres taller in the past 100 years.

The average height has increased from 171 centimetres to 180.6 centimetres. This information is available because they have measured young men entering the military since 1910.

They do not have the same statistics for women, but researchers know that women have also become taller.

A door that reaches your forehead

So, people were shorter before, but that's not the only reason why doors were low and beds were short.

One of the reasons why entrance doors were so low in log buildings is that they needed more logs above the door to make the house stable.

Log buildings are constructed with timber logs stacked on top of each other, according to Mogens With, a building conservationist at Norsk Folkemuseum.

Perhaps the doors were low to make it easier to defend against enemies who could enter with swords and axes?

“Well, that's an interesting theory, but often there were internal side walls placed close to the doorway and the door would open inward, making it almost impossible to swing a sword or an axe and deliver a deadly blow to the visitor’s neck,” With writes in an email to sciencenorway.no.

It might have had more to do with heat.

“The heat from the hearth rises up into the room and accumulates as a layer under the ceiling. The lower the outer door, the less heat loss,” he writes.

Not everyone had a bed

It is important to keep warm. That’s why it was also good to have shorter beds with more people in them.

They had to huddle together and sleep spooning each other.

Bjørn Sverre Hol Haugen is chief conservator at Norsk Folkemuseum and has written the book Søvn: Ei cultural history - Sleep: A cultural history.

“There were no standard dimensions for the beds, and people had to make them themselves. I have seen beds that are 1.57 metres long and some that are actually as long as our beds today, which are 2 metres,” he says.

If we look back several centuries, beds could usually be pulled out. That was because they took up even less space when not in use.

People did not have a typical living room like we do today, but rather one room that could be used for everything.

Servants and young people could sleep in the barn during the summer. And the milkmaid who looked after the animals often slept with them in the barn.

Easier to share a bed while sitting

“In the 20th century, we have grown in height by 10 centimetres. Our standard for beds only emerged in the 1970s. If you bought a bed before that, it would be 185 centimetres,” Haugen says.

However, there are also other reasons why beds were a bit shorter before.

“There are multiple explanations for why the beds were shorter before. People often slept in a sitting position, so they didn’t need such a long bed,” he says.

The old beds are often very wide, which makes them appear shorter than they actually are.

“People never slept alone in a bed. It was usually two people sharing a bed. Sometimes entire families slept together, with the child sleeping at the foot of the bed or between the parents,” he says.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik.

Read the Norwegian version of this article on ung.forskning.no

------