How dirty and stinky were medieval cities?

People in the Middle Ages were aware that a putrid urban environment was unhealthy, and according to Norwegian researchers they confronted the problem.

Lively communities for trade emerged in the Middle Ages and populations grew dense. This created opportunities as well as problems.

One of those worries was sanitation, specifically the treatment of human and animal waste.

A historian and professor at the University of Stavanger, Dolly Jørgensen, has researched waste disposal in Scandinavian and Northern European Medieval cities. She points out that in a medieval city with a population of 10,000, people typically produced 900,000 litres of excrement and nearly three million litres of urine annually. This was before such cities had underground sewage systems.

Added to that were the copious amounts of dung from livestock kept in the cities, from pigs, horses, cows and poultry.

An episode of the 2011 BBC TV documentary Filthy Cities describes the streets of London in the 1300s.

They were ankle-deep in a putrid mix of wet mud, rotten fish, garbage, entrails, and animal dung. People dumped their own buckets of faeces and urine into the street or simply sloshed it out the window.

Is this a true depiction of medieval cities?

Frequent epidemics

The medieval period in Norway began in the late Viking Age, lasting from around the year 1050 until the 1500s. This is when the first Norwegian cities that exist today were founded.

At the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), Axel Christophersen leads a research project on health and hygiene in Trondheim in the Middle Ages. He is a professor in historical archaeology.

Our medieval ancestors were plagued with diphtheria, measles, tuberculosis, leprosy, typhus, anthrax, smallpox, salmonella and other maladies.

They could also be poisoned by the ergot fungus Claviceps purpurea, which grew on cereals such as rye and triggered hallucinations - or made you «downright crazy», according to Christophersen.

The worst of such diseases was of course the Black Death, which began ravaging Norway in 1349, and struck again in later outbreaks up until the 1600s.

In their research project, Christophersen and colleagues investigate how citizens in medieval cities related to dreadful diseases.

"It was thought that they had no knowledge of how to deal with them. But research, partly in England, shows this to be wrong," says Christophersen.

"The goal is to study how health evolves from being a private affair, as it was, to becoming a public responsibility," says the researcher.

Dolly Jørgensen is among those who have discovered that medieval townspeople took steps in this direction. Hygiene was an important aspect of society.

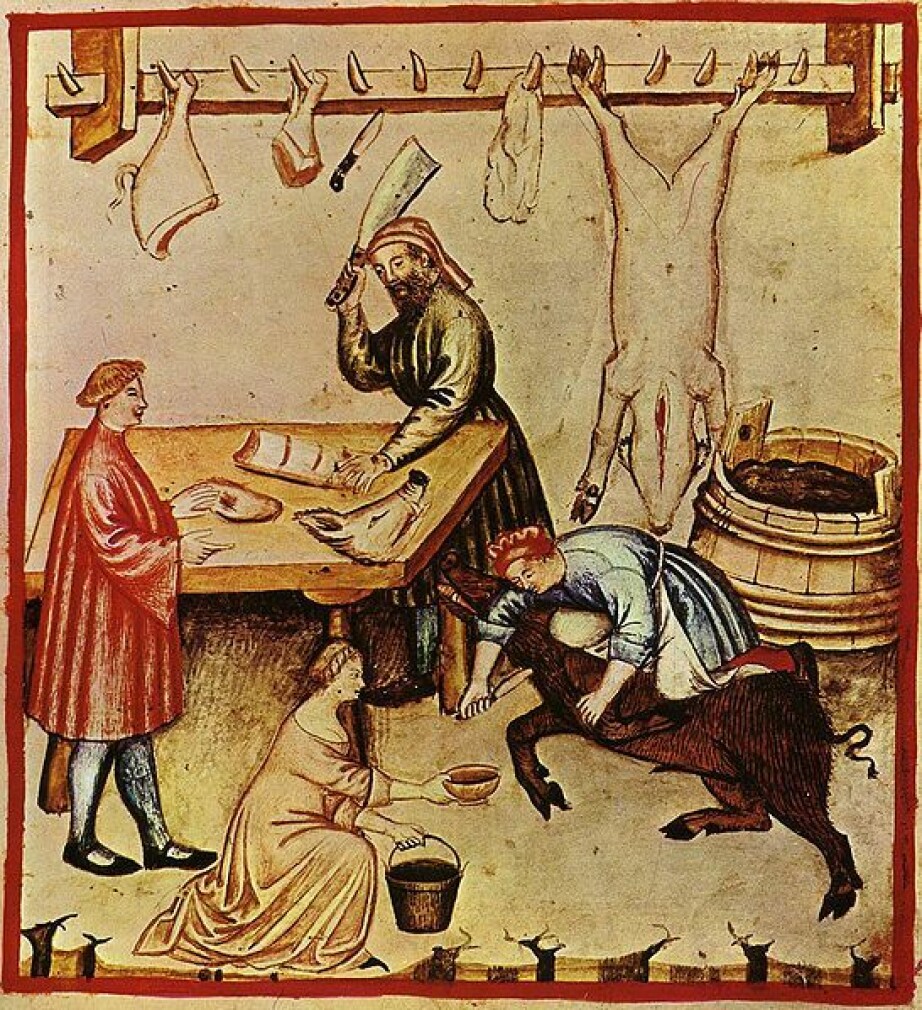

Butchery by-products

Dung or excrement was not the only filth that piled up in medieval cities. The waste products of various trades were equally pervasive.

Tanneries and textile production were messy businesses.

Worst were the slaughterhouses.

Intestines and heads had to be thrown somewhere. The intestines were cleaned of dung. Blood and water with fur or hair had to rinsed away. Complaints about butchers are found in older written sources from England.

Dolly Jørgensen has rereferred to them in her articles.

To name one: In 1371 the city council in York forbid butchers from discarding waste products in the river near a monastery.

So, the butchers started throwing intestinal and bloody waste near their walls and gates and at another spot in the River Ouse.

The friars complained again that the people of the city and country who used to attend their church 'are withdrawing themselves because of the stench and the horrible sights.' The monks also feared that 'sickness and manifold other harm' would result from this pollution.

The King decreed against the throwing of waste in the vicinity of the monks. Butchers solved that by dumping animal remnants in a graveyard. Bones were scattered around and attracted hungry dogs and birds.

Befouling rivers and drainage

It appears that the contamination of rivers was a problem for many medieval cities. But the authorities tried to prevent it.

In 1480 the Prior of Coventry complained that city dwellers daily through their dung, filth, and sweepings into the river. This caused a stench, or an 'evell eyre', as he called it. The Coventry Council wrote that the River Sherbourne had been 'stopped in its course by filthe, dong, and stonys,' writes Jørgensen in one of her articles.

Regulations were also required in Norway. In 1284 King Eirik Magnusson prohibited people from throwing their garbage and dung from the quays in Bergen. In Trondheim they were banned from tossing waste from the tanning process into the River Nidelva.

Dumping waste directly into watercourses was one problem but there were also systems of ditches that flowed into these same rivers.

Ditches, or gutters, were dug to lead away rainwater. But they were also a tempting place for citizens to get rid of any kind of waste.

It was obvious that the people Cambridge had enabled themselves of this quick solution in 1393. Complaints about clogged gutters filled with trash were delivered to the King. The nasty result was said to 'poison the air'.

The ditches in Trondheim did not drain into Nidelva, but rather to a swampy area in the middle of town

"Snorre even left us with a name for it. He wrote that the area was called Saurlid, which means 'the muddy place'. For centuries this was a place where waste and garbage ended up, eventually also from craftsmen and construction activities," says Axel Chrisophersen.

Such gutters or ditches took on more than rainwater.

A woman named Alice Wade in London was resourceful and ahead of her time. She made her own water closet with wooden pipes that led excrement directly into the rain ditches. Her neighbours were not particularly pleased.

Others took things a step further by building privies right over these ditches.

- RELATED: Was rape common in the Middle Ages?

'Stupid medieval people'

Despite the many repugnant examples, Dolly Jørgensen thinks medieval cities were better than reputed.

"There is this notion that medieval folks were ignorant, they didn’t realise that they could fall ill and they simply sloshed waste anywhere around town," says Jørgensen to Sciencenorway.no.

But this is not the impression she has after researching sanitation in North European medieval cities.

She says the complaints can be interpreted to show people did not accept living in a proverbial pigsty.

The classical opinion of the medieval cities is that they were filthy, overpopulated, had open sewers and people cared little about the way things looked, says Ole Georg Moseng, professor at the University of South-Eastern Norway. Moseng is an expert in medical history.

"The foundations of this myth were made at a time when Victorian cities were idealized as their opposite. Medieval cities were described as stinky cesspools, quite literally," he says.

But this myth has now been challenged by researchers. Moseng refers to four in particular, and Dolly Jørgensen was one of them.

Obligated to maintain the streets

Traces of the medieval urban past have been unearthed in Norway and other countries. The streets were cobbled. In Norway the streets were for some time paved with wood planks, while more durable paving stones were more the rule abroad. Townsfolk had no interest in walking about in filthy mud.

In Trondheim an entire city block has been excavated, comprised of 18 properties. The streets were divided down the middle. Axel Christophersen, who heads the research project 'Medieval Urban Health' at NTNU, thinks this was with good reason.

"One explanation is that they wanted to clearly mark off the individual residents’ responsibility for cleaning and maintenance."

The researchers can actually see there was a difference in how seriously various neighbours shouldered this responsibility. Some were diligently tidy, others weren’t.

"This goes all the way back to the 1100s," says Christophersen.

The oldest written Norwegian ordinance about cleaning operations is found in Magnus Lagabøte’s (Law-Mender’s) city regulations for Bergen from 1276.

"It stipulates that the public has to keep the streets clear and free of goods in the Christmas holidays, and that the street surface must be even. Bumps had to be levelled off. The archaeological material shows that the rules were systemized and linked to each property facing the street. It must have been the property owners' duty to obey the ordinances," says Christophersen.

Clear standards for privy placement

Building lots in Norwegian cities were typically 10-12 metres wide and from 20 or 30 to over 100 metres long. The houses were not that different than in Viking days. People more or less moved their farm into the city, informs Christophersen.

The main house was located in the middle and other buildings, such as stalls and barns, were to the rear.

"They were not dwelling in direct exposure to the street but were rather recessed back at their 'farmhouse'," says the professor.

Sales booths and workshops were located at street’s edge. Behind them were warehouses and other worksheds.

Some of these sheds housed animals. But the livestock was not allowed to run around freely.

Animal dung was preferably used as fertilizer or buried.

As for privies, they were placed at the very rear of the properties or in a compartment or closet in the house.

"The filthiest elements of human waste were assigned to particular spots. People did not squat and shit in front of the public – pardon the expression. This was done in a more private and secluded spot," says Christophersen.

"In most cities there were rules or norms for where latrines and privies could be located. They were not supposed to be a nuisance for the neighbours."

"In Trondheim we can just barely detect some fertilizer in the cultural layers. Human excrement is very rarely found and appears to have been buried in special places."

Waste bins and barrels turned up in many Scandinavian cities in the early 1200s, according to Dolly Jorgensen’s doctoral thesis from 2008. "Putting waste into barrels at the point of origin allowed it to be removed easily," she wrote.

Thick cultural layers of trash

Still, much of the waste would necessarily wind up on the ground. Archaeologists find meter-deep cultural layers from medieval times.

"What we excavate in the medieval cities is actually trash. It is household garbage and the discards from various types of handicraft and building activities," says Christophersen.

"It looks like people have tossed away household trash quite liberally. But this did not necessarily mean it was all thrown on the ground."

"We have to be a little careful not to think this is a cultural layer, it just means they threw stuff away here," says Jørgensen.

"Sources actually tell us that in the Middle Ages it was common to use trash as fill or a foundation when constructing buildings or when making a new street. We have sources showing that people were paid for bringing their discards to help make a foundation."

In any case, archaeologists see that cultural levels got thinner after 1350.

Why was that?

One cause was simply the Plague, the Black Death which killed even half or more people in the cities.

But it could also mean that people started ridding themselves of trash in another way, says Ole Georg Moseng, professor at the University of South-Eastern Norway. He is participating in the NTNU project.

- RELATED: Knife handle in the shape of a king from the 13th century found in the Medieval Park in Oslo

- RELATED: New runic find from medieval Oslo – this time it’s a name tag

Sanitation rules in the 1400s

Numerous written sources show that the city councils in European cities took charge, especially toward the late 1300s and into the 1400s. Jørgensen has documented that.

Tax was collected to fund streetsweepers. Those who dealt with ‘night soil’, the privy and latrine cleaners, collected human waste on a regular schedule.

Laws were enacted to level fines on people who polluted rivers or ditches.

Animal dung and other waste had to be hauled to dumps or at least somewhere outside of town. Piling up waste on the streets was prohibited. Some cities had rules for when butchers were to cart off their waste, and they could have a daily deadline when fishmongers had to clear away their mess from the street.

They tried to have butchers and any craftsmen who produced dirty waste relocated where they would not be so offensive.

This indicates that the city leaders were concerned about sanitation.

There are not as many written sources from this period in Norway. But the thinner cultural layers indicate that the country developed a new attitude toward certain types of trash, according to Christophersen.

The wet, organic waste disappears soon, but much lasts for modern detection, for instance sand, ashes, tiles, animal bones, and so on.

A block for blacksmiths was found in Trondheim that had been located outside the city centre. Smithies spewed toxic gasses.

Snorri Sturluson calls the block the 'Smithies at Ørene'. Archaeologists found this area in1987.

"It is located where sand has banked up outside of Trondheim, where the fjord and the river meet. Here there were one workshop after another in an area of several hundred square metres, and slag is found at a depth of one-and-a-half metres," says Christophersen.

"The prevailing winds would blow away the toxic gasses. This arrangement could have been an environmental measure. They recognized that this business could lead to disease. The same with the dyers, who worked with piss, and the tanners who worked with chicken droppings and semi-rotten animal hides. They were also ‘environmental swine’ who were wanted to work outside the cities."

Akin to thoughts about microbes

Christophersen thinks the measures could relate to the efforts to battle so-called miasmas, 'evil air'.

The understanding of disease in the Middle Ages had passed down from antiquity. There was the belief that an unbalance in nature could create miasmas, a putrefied air which was invisible or sometimes a mist. This could trigger disease. People believed miasmas resulted from natural phenomena such as earthquakes or lightning. But another source was rot, poorly buried corpses, animal cadavers and stagnant water, explains Medical Historian Ole Georg Moseng.

"It is a bit similar to our thoughts about bacteria and viruses," says Moseng.

"Miasmas can be transmitted through air, soil, water and even through objects. If you touch something that contains a miasma you can get it on your fingers. The notions of infection have been prominent all the way back to antiquity; there has never been any doubt that certain diseases are contagious," says Moseng.

People in the Middle Ages intertwined this understanding with their religion.

"There was believed to be a divine plan behind everything, a divine intervention in human fates," says Christophersen.

Evil air and abhorrent smells

Medieval humans drew a connection between stench and disease, explains Dolly Jørgensen. This probably conformed to their ideas about miasmas.

Jørgensen refers to examples from several cities in her articles.

She writes that in April 1371, the English King expressed strong apprehensions about flagrant disposal of waste from butchers in London. They routinely threw carcasses from Butcher’s Bridge into the Thames, and he called for a halt in practice:

"By reason of the slaughtering of great beasts in the city aforesaid, from the putrefied blood of which running in the streets, and the entrails thereof thrown into the water of Thames, the air in the same city has been greatly corrupted and infected."

As a result, 'the worst of abominations and stenches have been generated, and sicknesses and many other maladies have befallen persons dwelling in the same city'.

The correlation between stench and disease is expressed in another example from London.

One text describes deplorable conditions at the Fleet Prison in London in 1355. Filth from no less than eleven latrines and several tanneries had been thrown in a ditch outside the jail. This created an abominable stench and these odours were blamed for various diseases and grievous maladies afflicting the prisoners.

"We see that people were revolted by strong stenches. They wanted someone to clean up because this would not do," says Jørgensen.

Change in attitudes toward disease

Christophersen and Moseng think the Black Death prodded people to become more concerned about city sanitation.

"The reason why they carted waste out to public trash dumps, and they did this, hinges on a change in understanding of waste and its impact on health and well-being. I think the connection between bad smells and disease became increasingly accepted," says Christophersen.

Prior to that, it wasn’t convincingly clear for people that miasmas, or the foul airs, were linked to putrefaction and waste.

"We think the repeated outbreaks of the plague got people to change their practices. It overpowers the philosophical, almost cosmic, understanding of disease. People query, what is actually happening?" says Christophersen.

Ideas about God were also changing in the Middle Ages. Disease had been viewed as deserved and self-afflicted punishment for some sin or wrongdoing.

Later, it became increasingly common to think of the Christian God as merciful.

"If you fall sick, and leprous in particular, then you are one of God’s chosen ones. You should actually thank God because you give your fellow humans an opportunity to show mercy. You enable them to prove their worthiness with sacrifices and alms," says Christophersen.

Disease started to be less of a personal sphere and responsibility and more of something the community had to deal with, thinks the professor.

The seriously ill were isolated and during plagues some cities were quarantining ships. The many ordinances about keeping the city clean indicate that the authorities wanted to create a sound, healthy environment.

How filthy was it?

So, how filthy were the cities? Were people wading around in dirt, excrement and garbage?

It could be bad. When preparing for a parliament meeting in York in 1332, King Edward III lamented the odorous conditions.

"The king, detesting the abominable smell abounding in the said city more than any other city of the realm from dung and manure and other filth and dirt wherewith the streets and lanes are tilled and obstructed."

He wished to protect the inhabitants and those coming to the parliament and ordered a cleaning of all the streets.

The countermeasures that the city council had instigated earlier were described as 'straws in the wind' by researchers who have studied, medieval Italian cities. They thought the rules were not very effective.

Dolly Jørgensen, however, has studied written sources from a number of Northern European cities. She does not think careless littering and polluting were the norm. The fines and complaints she found involved deviations from the norm. People reacted to these.

"It’s like today. Most of us don’t toss stuff out the car window, but some people do."

Axel Christophersen concurs.

"It’s clear from archaeological source material that trash was emptied in both private and public spaces, but how widespread this practice was has been exaggerated. Without any regulations or norms regarding what could be tolerated of trash, the waste would have accumulated in amounts that far surpass what we find in the medieval cities we have investigated in the Nordic countries to date."

Ole Georg Moseng says much indicates that medieval people were concerned about aesthetics, health, and noise, So they wanted to organize their cities in a way that was functional and healthy.

Christophersen thinks the medieval cities did smell bad compared to what we find permissable now.

"Yes, it was dirty and unhealthy, but I think we have exaggerated how bad it was."

"The point is that they tried to do something about it."

Translated by Glenn Ostling

References:

Dolly Jørgensen: Private Need, Public Order: Urban Sanitation in Late Medieval England and Scandinavia, doctoral dissertation, University of Virginia, 2008.

Dolly Jørgensen: Cooperative Sanitation Managing Streets and Gutters in Late Medieval England and Scandinavia, Technology and Culture, 2008, pp. 547-567.

Dolly Jørgensen: The Medieval Sense of Smell, Stench and Sanitation, chapter in Les cinq sens de la ville du Moyen Âge à nos jours, red. Ulrike Krampl, Robert Beck and Emmanuelle Retaillaud-Bajac, 2013, pp. 301-313.

Dolly Jørgensen: Modernity and medieval muck, Nature and Culture, October 2014.

Ronald E Zupko & Robert A Laures: Straws In The Wind: Medieval Urban Environmental Law—the Case Of Northern Italy, Routledge, 1996.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no