Piecing together bits of Norway’s medieval history

Researchers at Norway’s National Archives and National Library are making new discoveries in centuries-old pieces of documents used to reinforce ledgers.

The National Archives of Norway’s stores some of its property three stories underground, beneath 25 metres of granite bedrock. Walls are thick around the seemingly endless shelves of books and documents. Pipes full of cables and wiring feed into holes in the walls. Before these perforations were made for electronics and power, the walls were capable of withstanding a nuclear attack.

A shower head protrudes incongruously from a white wall. You would not like to see it drenching all this valuable paper and parchment. But of course it was designed for washing off radioactive fallout on any survivors if the Cold War got hot. The thick walls and the unused shower tell the story of an earlier era.

Much older stories are found down here. The shelves are packed with state documents that have been in the hands of the National Archives since the institution was founded in 1817. Here are protocols from the Fredrikshald [now Halden] Toll Station on the border with Sweden, for instance. Of course census figures and statistics are dominant, just as even the most ancient notations on clay tablets are often linked to taxation and book-keeping.

Fragments of history

Tor Weidling and Espen Karlsen are employed respectively by the National Archives of Norway and the National Library of Norway. Their assignment is to hunt for bits and pieces of documents.

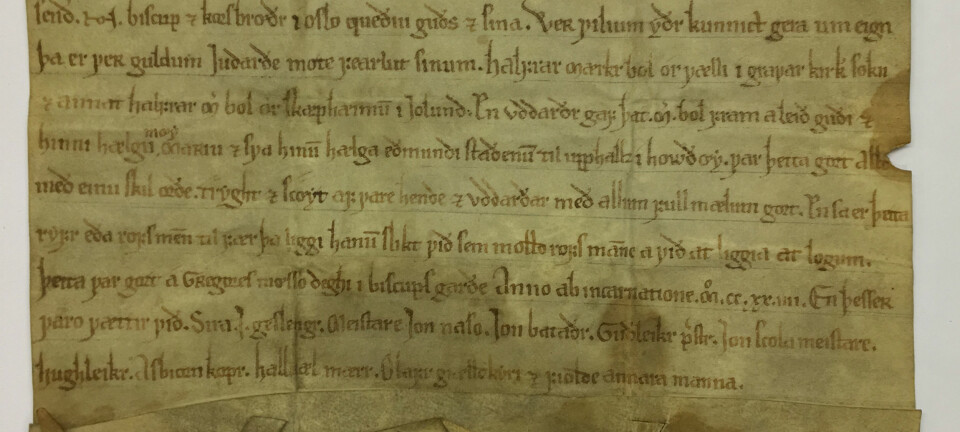

They page through old ledger books, trying to find even older fragments of manuscripts and documents used to bind them. The ledgers were sent from Norway to Copenhagen in the 16th and 17th centuries, when Norwegians were under Danish rule.

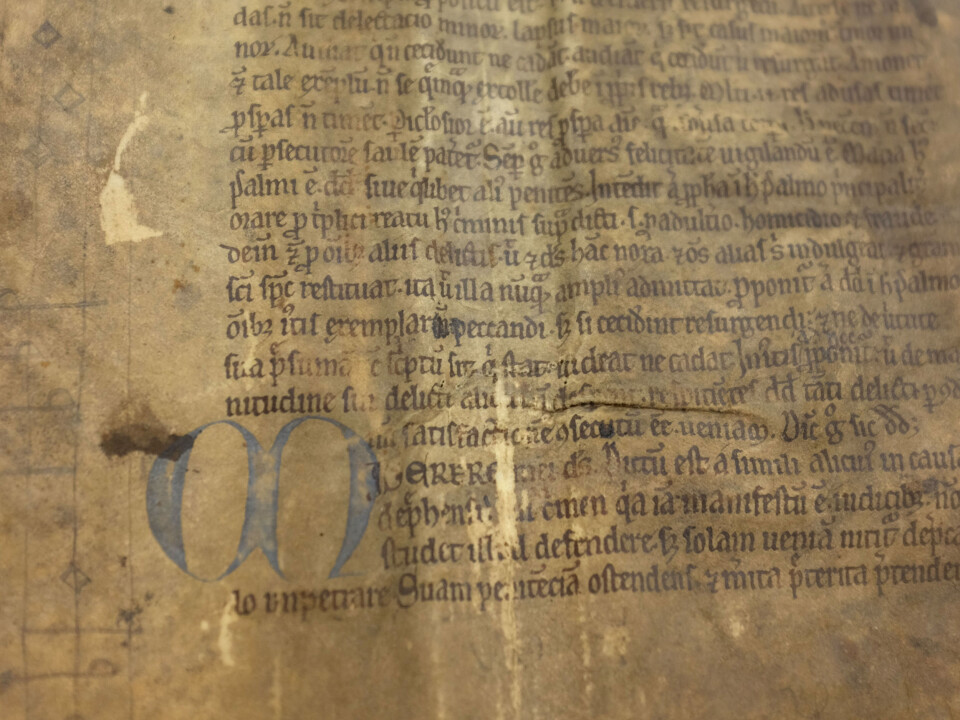

The books full of accounting figures were made of animal skin, or parchment. When making a book, the pages of parchment were sewn together with strong thread. Sometimes these threads ripped the parchment. So pieces of older parchment were added as patches to prevent the books from coming apart at the spine.

It is these recycled fragments that Weidling and Karlsen spend their time fitting together. Some of them contain texts and comprise parts of older manuscripts.

Specifically, the project involves identifying remnants of a book collection from the old Halsnøy Abbey on the Hardangerfjord in Hordaland County. This abbey on the spectacular Norwegian west coast was founded in 1163 and was dissolved with the Reformation in 1536. To date the researchers have found documents comprising nearly 40 books.

“All we have from Halsnøy are these fragments that we have found,” says Karlsen.

Their discoveries are contributing to knowledge about the Middle Ages and Norway’s cultural history.

Made in Norway

Karlsen’s curiosity was roused when he noticed the difference in sizes among the fragments of parchment. While most of the fragments used to strengthen ledgers were little bits, the ones from Halsnøy were fortunately quite large.

Weidling and Karlsen are sure these fragments are from Norway, even though the ledgers were sent to Denmark and spent centuries there. One indication is the discovery of such fragments on Norwegian accounts that had never been shipped south to Denmark. This means the fragments were added to the ledgers in Norway.

“We have not come across a single fragment which with any certitude was added in Copenhagen. But there are lots that undoubtedly were fitted to the books in Norway,” says Karlsen.

Weidling offers material from Norway’s Akershus County as an example. Feudal overlords, lensherrer in Norwegian, distributed various goods and materials to bailiffs, men in their employ who among other services acted as tax collectors. Each of these had their own way of binding these parchments together and different parts of the country had their disparate methods too. Documents from Akershus are thus physically discernible from documents originating in Bergen or Trondheim.

Weidling doubts that the Danes would have done things this way – using different methods of bookbinding for the different parts of Norway, especially as all of these are unlike the way Danes did these tasks in Denmark.

The bits of documents from Akershus could come from different churches. There were numerous churches in the county, which covers extensive countryside and towns around Oslo. It is difficult to determine which churches the fragments come from.

It is easier in smaller and more isolated locations, which is why documents from Halsnøy Abbey stand out. It was rather distant and isolated from Bergen and other towns and communities, making it easier to determine exactly where the pieces come from.

After the Reformation, the administration of the Halsnøy district housed itself in what had formerly been the Abbey, so it is easy to imagine that when old parchments were needed, administrators just took those left by the medieval men who had formed a monastic community living under the rule of St. Augustine.

Recycling

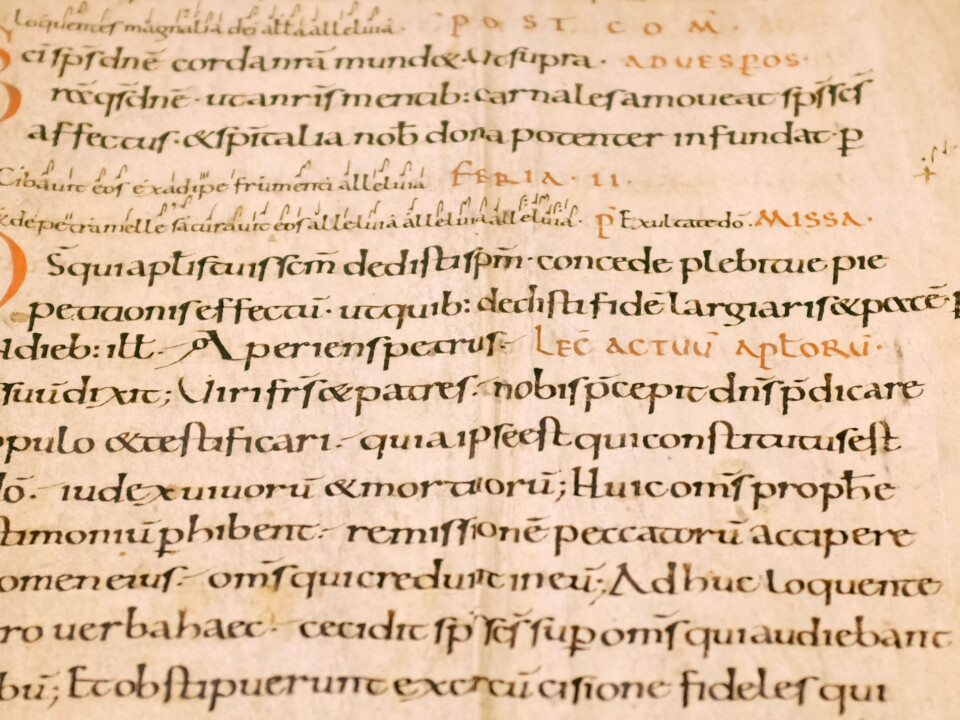

The documents from Halsnøy Abbey were written in Latin, as were all the other bits and pieces that Weidling and Karlsen hunt down. Similar projects have run earlier with fragments of old Norse documents.

The recycled abbey documents were sometimes liturgical, mostly linked to church services. Song books are among them. Fortunately for posterity, as society and religion changed, things that were no longer of any use were not always discarded.

“This is definitely an example of recycling,” says Weidling.

Parchment came in a limited supply and even the elite in Norway who worked for the government centuries ago had to use it sparingly. It is a durable material but expensive, made from an inner layer of hides of calves or sheep. If large parchments were demanded the skin of a whole sheep was needed to make just one page.

“The most extravagant I have heard of was a book made from 500 sheep,” says Karlsen.

So books were expensive. Of course the meat from the livestock did not go to waste, but plenty of skilled work went into making good parchment. To draw a comparison, the production of a book could represent a cost amounting to tens of thousands of dollars in today’s currency.

A century or two

The practice of recycling parchment was most common in the 16th and 17th centuries. From the mid-1600s it started to decline.

“Some of the latest documents we have found using remnants from Halsnøy Abbey are from 1647,” says Karlsen.

As the 1700s approached, new parchment was used more often than old here on the Hardangerfjord. Weidling and Karlsen are not entirely sure why, but one explanation comes readily to mind.

“Perhaps the supply of medieval parchment manuscripts was depleted. Even at Halsnøy there had to be a limited number of them,” says Karlsen.

--------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling