Who painted pictures like this on rock walls in Norway 5000-8000 years ago?

Researchers are uncovering the mysteries of rock paintings millennia after they were created. More and more paintings are being discovered.

Jan Magne Gjerde is an archaeologist and works for the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research (NIKU) in Tromsø. One day he got in his car and drove almost 6000 kilometres.

The trip took him through Norway, Sweden and Finland and all the way up to the Kola Peninsula in north-western Russia.

All in all, Gjerde has travelled over 180 000 kilometres by car in recent years to gain more insight into something few people know exists: art painted directly on rock walls in the far northern reaches of Europe.

The paintings were created by an unknown people in the far northern Nordic countries and northwestern Russia – perhaps as much as 5000-8000 years ago.

The Tromsø archaeologist's project when he hopped into his car that day, was to study this strange rock art in as many places as possible all in one trip.

That's how he made a discovery.

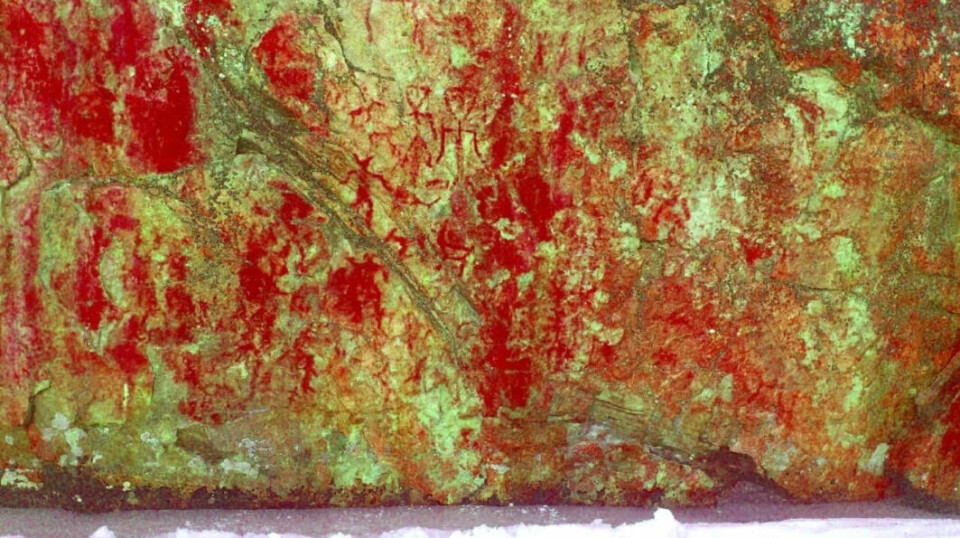

Painted directly onto the rock wall

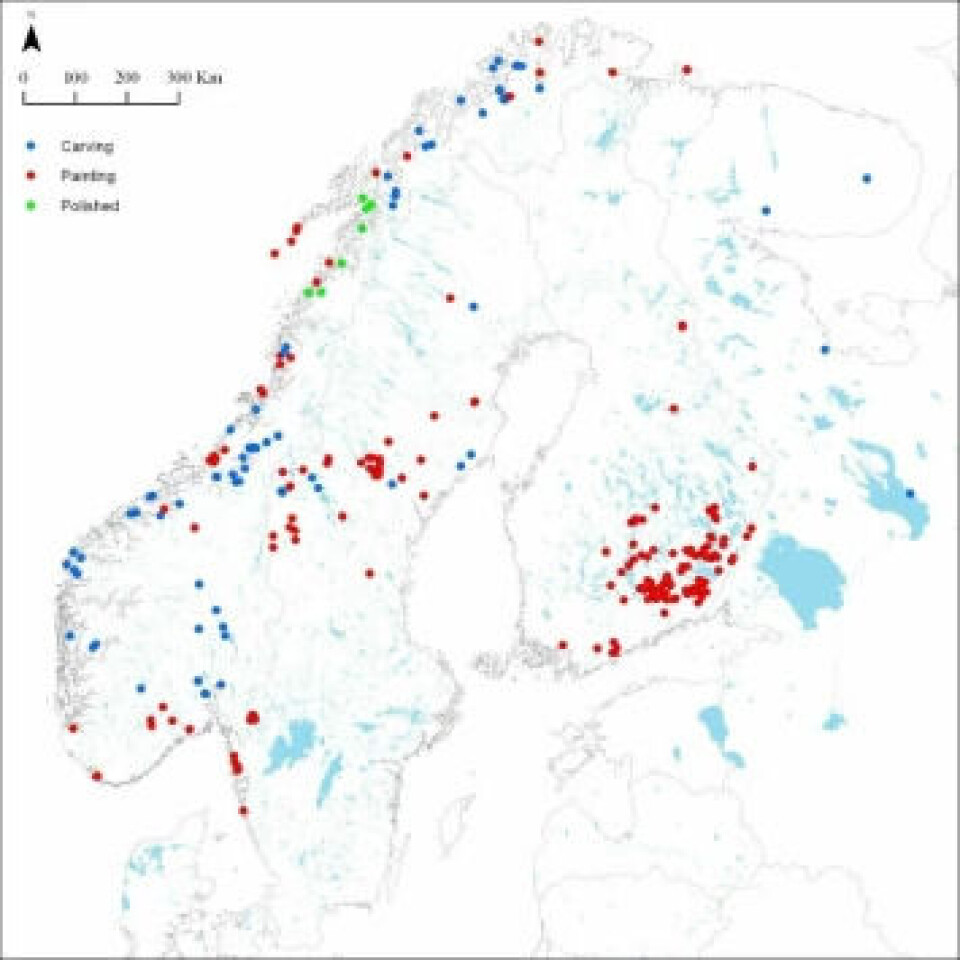

You’ve likely heard of petroglyphs. Thousands of such images carved in stone have been found in Norway, Sweden and Russia. These rock carvings have managed to last for thousands of years – which might not seem that strange, given that the images have been etched into stone.

But few people know that curious researchers and other people are now also finding a number of rock paintings in Norway and its neighbouring countries.

You might find it harder to imagine how a picture painted with simple natural pigments right on an exposed cliff face in the far north could survive several millennia of rain, cold, snow, ice, sun and wind.

Older than petroglyphs

That’s why until a few years ago, rock art researchers in the Nordic countries believed that rock paintings had to be younger than rock carvings.

Several experts have now changed their minds. They believe that some of the rock paintings might have been created at the same time as some of the oldest Stone Age rock carvings.

Some rock art is found inside caves in the Nord-Trøndelag and Nordland regions of Norway. But most paintings are found on exposed vertical rock faces with overhangs.

Many more paintings have been discovered just in the last 10-20 years.

Gjerde believes that he has looked at perhaps 90 per cent of all the oldest rock art in Norway, Sweden, Finland and north-western Russia his car trips.

You’re about to find out what he discovered.

How old are the paintings?

“The very first rock painting was found in Finland just over a hundred years ago. The Finns have since discovered 150 more sites with painted rock art,” says Gjerde.

His hunch is that Finns, Swedes and Norwegians will discover a good many more pictures in the coming years.

He emphasizes that the age of the rock art is still uncertain. Dating the pigments used by Stone Age people is difficult.

Gjerde believes the oldest rock paintings known in the Nordic countries are most likely 7000 to 8000 years old. The youngest images might be a ‘mere’ 2000 to 3000 years old.

Always by water

The archaeologist observed one thing very clearly as he travelled from one rock art site to the next in Norway, Sweden, Finland and all the way up to the Rybachy (Fisher) Peninsula on the Kola Peninsula in Russia’s extreme northwest.

“The vast majority of rock paintings we know of in the Nordic countries today were painted very close to water,” says Gjerde.

In Norway, the pictures were often painted on a rock cliff by the sea or close to what was a Stone Age beach. The oldest rock art in Finland and northern Sweden is often found on the shores of inland lakes and rivers.

Several of the cliff walls with rock paintings in Finland and Sweden drop straight down into lakes. In Norway, the rock walls might have descended into what was once the sea, but which today are far inland due to the land uplift after the last ice age.

This pattern is well known to archaeologists who research rock carvings from the Stone Age and Bronze Age. The rock art was very often made by people who must have stood on the shore or on smooth rocks sloping down to the water.

Gjerde was about to discover something even stranger.

Did Stone Age people see faces in nature?

“In a lot of the places where Stone Age people painted their rock art in the Nordic countries, natural features have the shape of a face.”

“Wherever people saw faces, that’s where they painted their pictures,” Gjerde says.

The archaeologist has now found this phenomenon in so many places that he is convinced face shapes must have been an important reason people chose exactly these rock cliffs to make their art.

“This can’t just be coincidence,” says Gjerde. He emphasizes that he was not the first person to come up with this idea. Finnish researchers have observed the same thing.

The most ancient art

The Stone Age in the Nordic countries lasted from the end of the ice age about 10 000 years ago until about 3700 years ago. During that period, hunters and gatherers created several thousand rock carvings in stone.

The largest rock carving area in Northern Europe from that period is at Alta in Finnmark, the northernmost part of Norway.

The people who lived in the Bronze Age in the Nordic countries – that’s 3700 to 2500 years ago – were part of an agrarian culture. The well-known petroglyph scenes in Bohuslän in western Sweden and in Østfold in southern Norway are mostly from the Bronze Age.

The newest rock carvings in the Nordic countries were probably made in the early Iron Age, around the same time as Greek antiquity.

- You can read more about new research on the Bronze Age in the Nordic region in this article: Was there a Viking Age in Norway — 2000 years before the Vikings?

The artwork most likely originated before the start of farming.

Gjerde believes that most of the rock paintings must have been made by Stone Age people who lived by hunting, trapping and fishing – in other words, people who lived here before agriculture came to the Nordic countries in the Neolithic period around 4000 years ago.

“We have several examples of rock paintings in Sweden, Norway and Finland that are 6000 to 7000 years old, late in the Palaeolithic (Old Stone Age),” he says.

“The very oldest pictures could be as much as 8000-9000 years old. If so, that would place them earlier in the Palaeolithic.” Gjerde stresses that these are pretty uncertain dates.

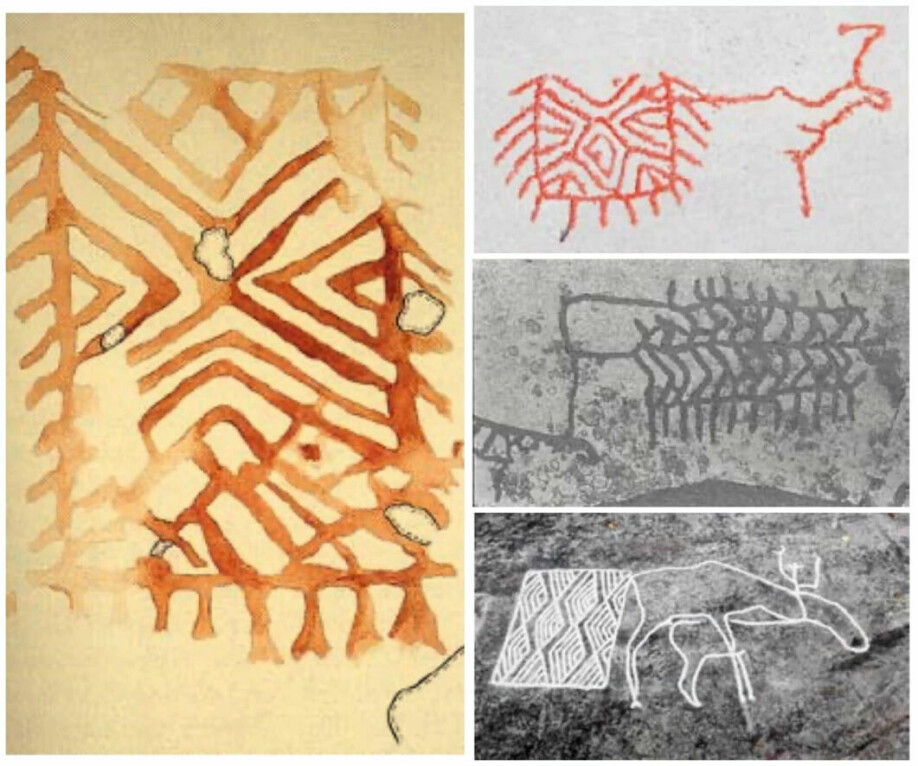

Moose, humans and geometric patterns

Moose made up the most common painting motif that Gjerde saw in the large area in northern Europe often referred to as Fennoscandia (Finland + Scandinavia). In the farthest north regions he found more reindeer.

“Stone Age people obviously had clear preferences for what they chose to depict,” says Gjerde. “Swans dominate on Lake Onega in Russia. By the White Sea, the white whale is prominent. In Alta, the reindeer are predominant. Deer dominate in western Norway."

The Stone Age people in the Nordic countries painted people, too.

"Inside Norwegian caves, you often find human figures," Gjerde says.

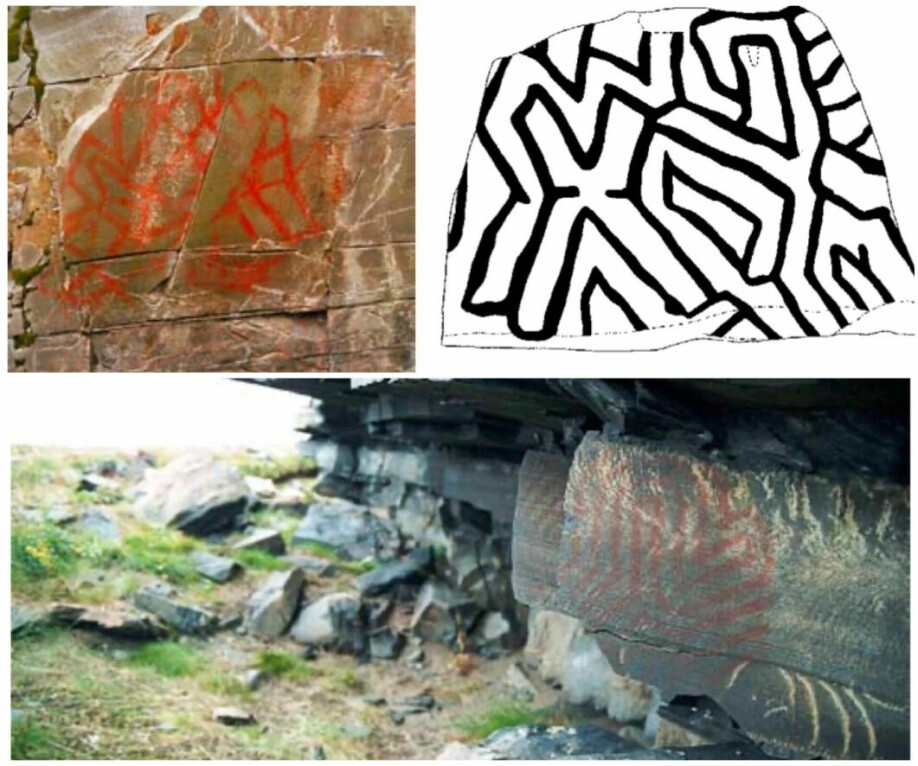

The archaeologist has also observed a lot of geometric patterns.

He observes striking similarities in the motifs, even over what could be several thousand years.

At the same time, he sees clear signs that the motives also evolved over time.

Just the tip of the iceberg

For the past 25 years, the archaeologist from Stadt in Western Norway has been photographing and documenting rock art.

In recent years, he has found that high-resolution photography and new digital programs for image processing make viewing the rock paintings much easier – and clearly more exciting.

Now Gjerde and his colleagues are discovering far more ancient rock paintings in the Nordic countries.

“Out in nature, you can walk right past a cliff face without seeing any human-made figures.”

“But today's digital photography tools and super high-resolution images make it possible to discover images that we can’t see with the naked eye,” the archaeologist says.

He is convinced that a lot of rock art remains to be discovered in Norwegian and Nordic nature. Modern cameras and image editing can help us locate these images.

“I think we’ve only seen the tip of the iceberg so far,” Gjerde says.

But who painted the pictures?

Fantastic painted pictures from the Stone Age have also been discovered in caves in France and Spain.

“Footprints in the sand inside caves in France and Spain tell us that children might have been present when people made their Stone Age art there.”

Gjerde notices that the traces of paint on rock walls in the Nordic countries are often finger width, something he has observed in Norway, Finland and Sweden. This could mean that someone might have used their fingers to paint the pictures.

“In several places the painted lines correspond best to a child’s finger size,” he says.

Gjerde wonders whether what we see could be linked to some kind of rite of passage from far back in the Stone Age? Maybe it involved a ritual where a person went from being a child to becoming an adult?

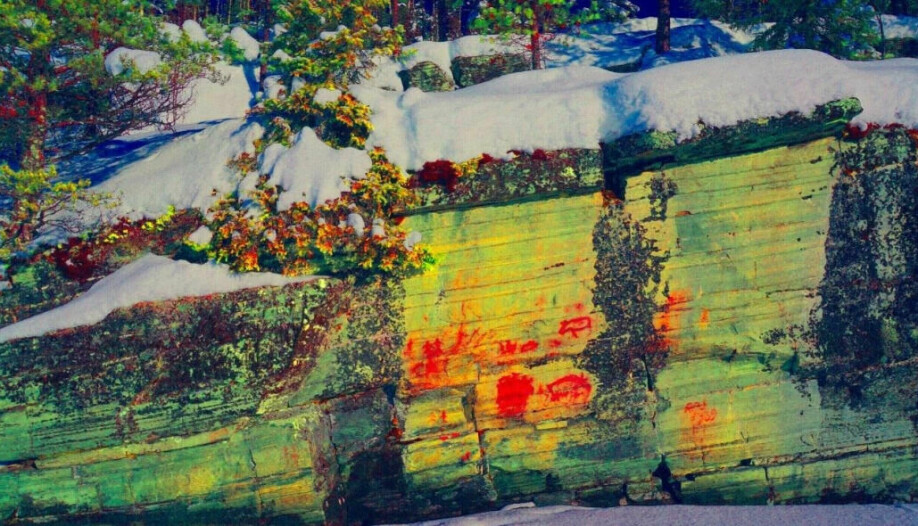

People were standing on a lot of snow

In a separate study of 75 places with rock paintings by lakes in Finland, Sweden and Norway, the archaeologist is interested in how people clearly must have been on the water when they painted these pictures.

Sometimes they might have been in a boat. But Gjerde thinks it’s just as likely that people stood on the ice in the winter, when the lake was frozen.

“I discovered that it’s much easier to get to these places in the winter than in the summer,” says Gjerde.

He reminds us that Stone Age people in the Nordic countries had both skis and snowshoes, a motif we find depicted in petroglyphs.

Stranger yet is that the Stone Age rock art was often painted far up on cliff faces, often so high up that today they are hard-to-reach places.

“People might have had ladders that were placed on the ice. Or they could have been suspended with ropes from above.” But Gjerde doesn’t think either of these options is probable.

The archaeologist believes the explanation might be as simple as that Stone Age people were standing on a lot of snow on the frozen lake. In the picture of Gjerde further up in the article, he is standing on the frozen Finnish lake Värikallio and pointing out how high up the pictures are on the cliff face.

What pigments did they use?

Archaeologists have long believed that the pigments used for the rock paintings must be iron oxide.

By burning this mineral that they extracted from the earth, Stone Age people could obtain the colour oxide red.

Earth pigments is a collective term used for such colours today.

“Recent analyses elsewhere in Europe point to dyes from plants that were also used,” the researcher says.

The mystery of conservation

Then we come to the mystery of how in the world these rock paintings could survive thousands of years of Nordic rain, snow, cold, ice, sun and wind.

How can pictures that might be upwards of 8000 years old have remained on these far northern rock walls to this day?

Admittedly, many of the images are partially protected by rock overhangs. But these paintings used very simple dyes and pigments, which were exposed to the forces of nature for millennia.

Rock varnish explains it

The somewhat mysterious explanation for how rock paintings have lasted for so long lies in the formation of what is called rock varnish.

The coating is made mostly of silica, which can leach from the rock. This mineral forms a gel-like substance that can almost be compared to a layer of varnish on top of the Stone Age paint.

The ancient art of painting became part of the rock, in a manner of speaking.

“Finnish researchers have investigated this further. They believe that this rock varnish formed right after the picture was painted,” says Gjerde.

“The rock varnish might have been created when dew formed on the rock for the first time after the picture had been painted, and the sun then heated up the dew. That might be how the image was preserved.”

But nature certainly hasn’t helped to preserve all painted Stone Age art. In many places, rainwater has undoubtedly washed away the images. In other places the sun may have contributed to heat and cold interacting where it shone directly onto the pictures, which eventually destroyed the rock underneath the painting.

Today, Gjerde and his colleagues fear something completely different. They are concerned that curious people could ruin the pictures, either due to ignorance or pure vandalism.

Gjerde and other archaeologists are therefore somewhat reluctant to share exactly where some of the rock paintings are.

Is it about shamanism?

Retired archaeologist Reidun Laura Andreassen was a county conservator in Finnmark in Northern Norway for many years.

She has been interested in how the rock paintings in the Nordic countries fit into a shamanistic tradition, with links to Siberia and much of the old world in general.

“Throughout Fennoscandia and far into Russia, we find patterns from the Stone Age that resemble each other. We can recognise these patterns from a large geographical area,” Andreassen says to sciencenorway.no.

“How much contact people had with each other in the Stone Age is difficult to know for sure today. Rock art is a universal language, where similar figures can be found in different places and express the same cosmological ideas.”

Andreassen believes that these figures, which combine geometric patterns and animals, could be interpreted as the shaman's trance journey. When the shaman makes this journey, the mantle is central and the helping spirits can be animals like reindeer and elk.

Stone Age cosmology

Andreassen’s use of the term cosmology in this context is about explaining how the world is connected and what the world consists of.

Cosmology, more than religions, is also about human beings’ place in the universe and an expression of people's need to place themselves in a larger context.

We are familiar with nature religions among the Sami, Siberian peoples, Indians, Australian Aborigines and many other societies in the world where shamanism has been widespread.

The shaman's task is to help communicate between humans and the spirit world. He or she makes contact with the "other side," for example by hitting a drum and going into a trance.

“Shamanism often involves making trips to a kind of underworld to get protection from the spirits that are there,” Andreassen says.

“In Norway, we know shamanism from the Sami and in Old Norse society. Among the rock paintings in Norway, I think that especially the figures that we find on the rock in Transfardalen outside Alta on the northern coast of Norway lend themselves to this kind of interpretation,” she says.

Andreassen believes that some of these rock paintings located a little bit north of downtown Alta can probably be dated as far back as 8000 years ago.

In that case, it makes them some of the oldest art we know about in Norway.

Death rituals

Andreassen suggests that these geometric figures can also be interpreted as part of death rituals.

“The figures can be interpreted as symbols of transition – a death passage – where you have to go through a labyrinth to get to the other world, a place where it isn’t possible to find your way back.”

On the same rock wall, paintings of human figures have been found with their heads down, often perceived as the dead and reinforcing this interpretation.

Several Norwegian archaeologists who have studied the rock paintings have been concerned that the paintings belong to a different tradition than the petroglyphs. But here Andreassen disagrees.

“They’re two sides of the same tradition, and both can be put into a shamanistic context. Rock art is a universal language that we find in many places in the world.”

“Maybe this art reveals to us how people in the Stone Age maintained contact with each other over long distances,” she says.

- RELATED: People have lost arrows and other objects at this spot in Jotunheimen — for more than 6000 years

Was the population in Norway replaced?

Astrid Nyland is a researcher in the Museum of Archaeology at the University of Stavanger.

She has been particularly interested in the locality of Honnhammaren in the Nordmøre district.

Here we find something very special: rock carvings with boat pictures that have been carved into the rock right next to and partly over what are probably much older rock paintings with animal figures.

Around 4000 years ago, many people may have come to Norway by sea from Jutland in Denmark. These people belonged to what scientists call the Bell-Beaker culture.

From Sørlandet they travelled north along the Norwegian coast, first to Western Norway and then even further north. Archaeologists can follow them in the wave of changes found in the archaeological material from many thousands of years ago.

Nyland is of the opinion that these new people did not replace the existing hunter-gatherer culture in Norway and the Nordic countries, but they must certainly have influenced it. They also formed the basis for the establishment of Norway’s agrarian society in the Bronze Age and Iron Age.

New people from the south

“The activity, in which people who belonged to an agricultural culture drew their boats on top of much older rock paintings with animal figures, perhaps expressed that the new farming culture from the south had come to stay,” says Nyland.

In an article that Nyland wrote for the journal Viking in 2011, her main thesis was that the special rock art in Nordmøre could be about feeling and showing belonging to a place and to traditions.

Maybe the art was about connecting with people who had been in this place in Western Norway before the new people came from the south?

“The petroglyphs with the boats are perhaps 3000-4000 years old. The pictures of the moose and reindeer could be a thousand years older,” says Nyland.

The researcher is also interested in what might have transpired when the people from the old Stone Age culture in Norway met the first wave of people who came from the south with their own agrarian culture.

Today's Norwegians are most likely descendants of the latter.

“What happens when you meet people who have a completely different way of living than you do?” Nyland asks.

“How did these strangers get along with each other?”

The pictures at Honnhammaren may tell us something about how the new Norwegians 3000 years ago wanted to connect with the people of the past who were in Norway before the ancestors of today's Norwegians.

Last holdout of Stone Age people

The people who once created the old rock paintings in the Nordic countries are probably not the ancestors of today's Norwegians, Swedes and Finns.

DNA studies from 2009 have been able to reveal more information on this topic.

But the hunters and gatherers who came here in the Early Stone Age just after the last ice age, and who made all or most of the rock paintings that you’ve seen and heard about in this article, may have lived side by side for a period with the early farmers who came here from the south in the Neolithic, or Late Stone Age. We currently know little or nothing about their coexistence.

The Nordic countries might have been one of the last holdouts in Europe for Stone Age people who did not cultivate the land.

References:

Jan Magne Gjerde: Journeys in Stone Age Rock Art and its Research History in Northernmost Europe. Rock Art Research, 2019. Preview.

Jan Magne Gjerde: Snowscapes of Rock Art: Seasons and Seasonality of Stone Age Rock Art in Northernmost Europe. Chapter in the book Perspectives on Differences in Rock Art, Equinox Publishing, 2021. Abstract.

Jan Magne Gjerde: Rock art and Landscapes: Studies of Stone Age rock art from Northern Fennoscandia. Doctoral dissertation at UiT, 2010.

Reidun Laura Andreassen: Paintings and carvings – rock art in Fennoscandia. The journal Viking, 2008.

Reidun Laura Andreassen: Rock art in Northern Fennoscandia and Eurasia – painted and engraved, geometric, abstract and anthropomorphic figures. Adoranten, 2008.

Astrid J. Nyland: Båtfigurene på Honnhammer – Uttrykk for historisitet og møte mellom kunnskapssystemer på Nordmøre (The boat figures on Honnhammer – Expression of historicity and meeting between knowledge systems at Nordmøre). Journal Viking, 2011.

Helena Malmström et.al: Ancient DNA Reveals Lack of Continuity between Neolithic Hunter-Gatherers and Contemporary Scandinavians. Current Biology, 2009.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no