The urban space is sexualised and misogynistic

“Our unconsciousness is shaped by sexist messages from advertisements. The public urban space in one of the world’s most gender equal countries is not designed for women,” according to social geographer Emma Arnold.

Until 2000, graffiti was legal in certain places in Oslo, before the City Council introduced their zero tolerance policy, which involved full criminalisation of graffiti.

“The goal was to explore how this policy affected the urban landscape,” Emma Arnold explains.

She has written a PhD thesis at the University of Oslo about aesthetics and sexualisation in the public urban space. In her search for answers, she conducted a somewhat untraditional fieldwork by applying so-called psychogeographic method, and explored major parts of Oslo and Stavanger by foot and through a camera lens.

The psychogeographic method involves wandering around the city with no specific plan.

“The method was introduced with the situationists, that is, avant-garde artists and urban researchers in Paris in the 1950s and 60s. You have to dare to get lost,” explains Arnold, who covered approximately 300 kilometres during the period 2013 to 2017.

Pushy advertisements

“The project was originally not about advertisements at all, and even less about gender. The focus was street art and graffiti in urban spaces,” says Arnold, who is a street artist herself.

Then the project took a new, unexpected turn.

“After a while, I began doing fieldwork in the evenings and at night, and noticed that the urban space changed,” she explains.

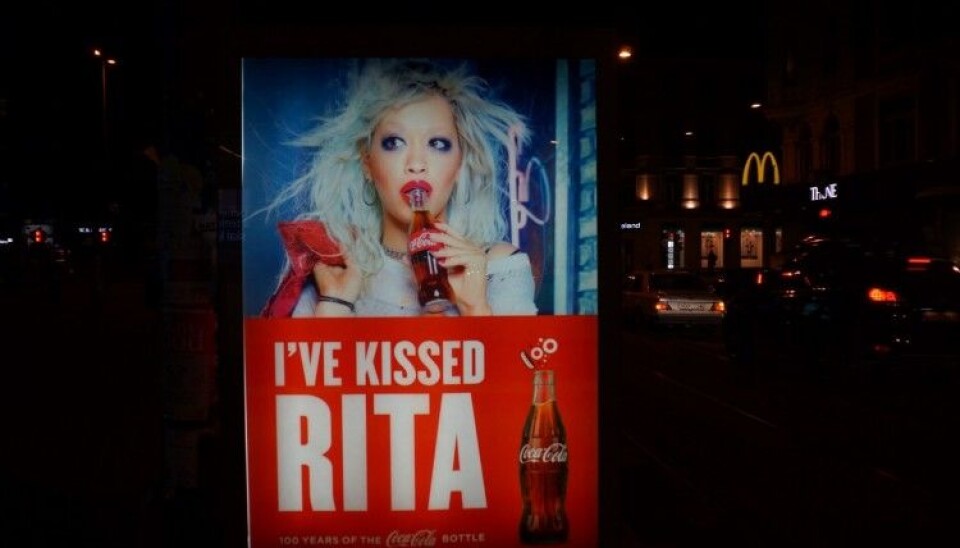

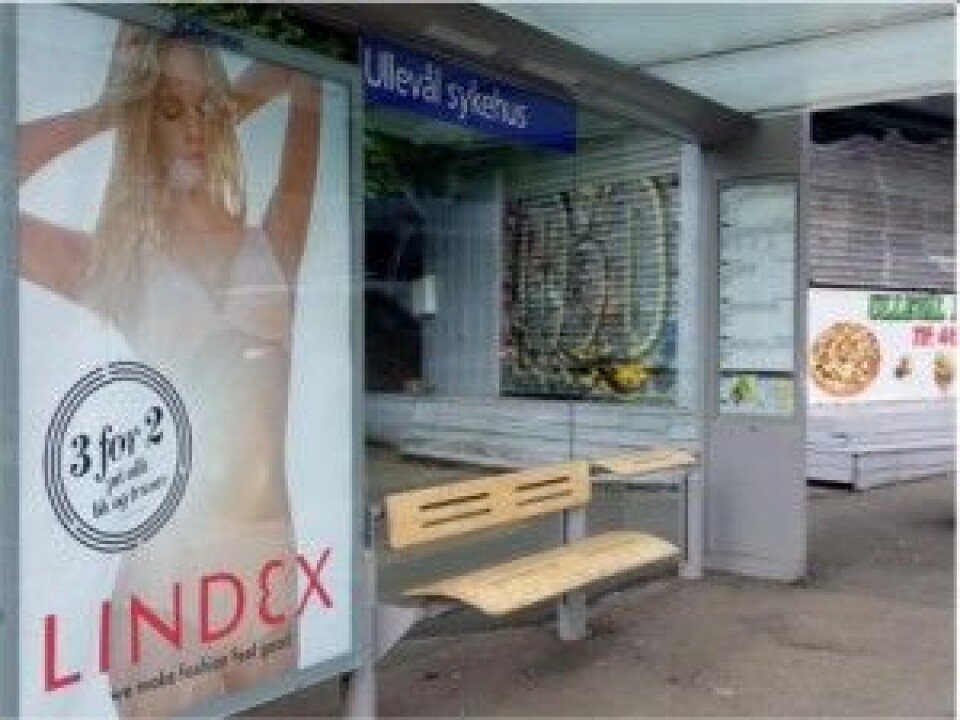

“Billboard towers are lit up in the evenings, and you notice them better. The contrasts become more obvious than in daylight.”

In Arnold’s opinion, advertisements that objectify women are conspicuous when seen in lit up billboard towers. She thinks the scale of such advertisements will increase drastically over the years to come.

According to the PhD thesis, Oslo Municipality and the advertising agency Clear Channel have recently agreed upon a contract involving 700 new spaces for advertisements in the city. The contract is worth 750 million Norwegian crowns.

“These billboard towers have become increasingly widespread in correlation with the growth of public-private partnerships,” the researcher explains.

“The municipality collaborates with commercial agents such as Clear Channel and JC Decaux about the arrangement of the public urban spaces.”

The billboard towers have been met with protests from several activists who are critical toward how commercial expressions are prioritised instead of political expressions.

Arnold, who is originally from Canada, did not only notice how advertisements repressed other aesthetic expressions. In her opinion, they also affect women negatively.

“During my fieldwork, I became more self-conscious when I was exposed to the advertisements,” she explains.

According to Arnold, the advertisements contribute to an unhealthy body-image pressure and a persistent sexualising of the urban space.

“One of the things I found attractive when I settled in Norway was that the country is famous for being gender equal. Yet the public urban space is pervaded with sexist and gender stereotypical advertisements,” she says.

“Although my project originally was about something else, it became impossible to ignore the advertisements. This also emphasises their visual power. The pictures attract the audience. They distract and repress other images that we encounter in the city,” she says.

The advertisement’s ideological function

In her thesis, the researcher criticises the advertising industry for reproducing images of women as consumer commodities. Based on feminist theories by scholars such as Laura Mulvey, who in a famous article from 1975 was the first to write about ‘the male gaze’, Arnold explores the advertisement’s ideological function.

“What do you mean by the advertisement’s ‘ideological function’?”

“Advertising is not just about selling goods. Both consciously and unconsciously, advertisements reflect and reproduce social meaning and difference. We see expressions of this when women are depicted as highly idealised and only connected to beauty, motherhood and sex,” says Arnold.

“In some advertisements, women are depicted as highly sexualised, in positions that make them look like they are masturbating or have oral sex.”

According to Arnold, this sexualisation is sexist:

“It is conspicuous that men are never depicted in similar positions,” she says.

In her opinion, images that connect women to sex are not problematic in themselves. She emphasises that we need to distinguish between erotic images and images that are solely meant to titillate or shock.

“The City Council has no regulations concerning outdoor advertising. Additionally, some advertisements are designed by international enterprises that do not necessarily consider a Norwegian audience when they design their advertisements,” she says.

“The result thus becomes more gender stereotypical and standardised.”

The thesis describes the objectifying advertisements as expressions of women being considered as a commodity created by and for men. This enhances the existing power imbalance between women and men: “At night, women’s vulnerability may increase in line with them being increasingly sexualised in the public urban space.”

The mere presence of the advertisements also affect women in other ways, according to the researcher:

“Women constantly discipline their own bodies and their visibility in the city at night-time. A common strategy is to tone down and hide their sexuality.”

Feminist geography

Emma Arnold is originally an urban and cultural geographer, but she has been inspired by feminist geographers such as Gill Valentine and Rachel Pain. They were among the first to write about ‘the geography of fear’ in the 1980s and 1990s. Until then, the discipline had primarily focused on buildings and physical outdoor spaces, as well as on how industrialisation and capitalist economy affect and restructure cities and landscapes.

Women’s own experiences of urban space and the way in which urban spaces reproduced power and gender relations was a blind spot in the existing research at the time.

“A human being’s social position affects how freely one moves around in the public space,” says Arnold.

Cultural norms force women to take precautions in order to avoid sexual violence and harassment. As a result, the public space becomes restrictive and misogynistic.

“Many women avoid certain places and do not have an experience of the city as open and inclusive.”

The city’s ‘invisible walls’

In her thesis, Arnold describes one specific episode during a nightly walk near Stensparken in Oslo: “I was scared. It felt as if there was suddenly an invisible wall in front of me. Despite my research objective to explore this space, and despite my strong desire to succeed, I just couldn’t,” she writes.

Arnold wanted to explore this fear. Rather than treating her emotions as an internal phenomenon, she – like other feminist urban geographers – analysed fear as a structural and cultural construction.

“Fear affects the way in which people move through the city and experience the city,” says Arnold.

The physical experience of fear and the feeling that certain parts of the urban space was not accessible led to Arnold’s coinage of the term ‘invisible walls’.

“What does this term entail?”

“The term has much in common with the feminist concept ‘glass ceiling’,” she says.

“It has to do with the invisible barriers that women experience, which make the public space appear more or less accessible and inviting at various times of the day.”

According to Arnold, the urban space is particularly excluding for women who break with established gender norms. Lesbian women or women who in various ways challenge the heteronormative, risk homophobic violence and various types of gender-based hate crime, Arnold writes in her thesis.

Wants more research on sexualised advertisements

Feminists have long argued for marking retouched advertisements, as stereotypical and sexualised images of women result in body-image pressure and unhealthy beauty ideals.

Yet no one in Norway has previously done any research on how advertisements contribute to a sexualisation of the public urban space and how this actually affects people.

Using the British urban geographer Phil Hubbard’s works on the sexualisation of urban spaces as a point of departure, Arnold is the first to explore this topic in depth here in Norway. She is hoping that others will follow her example with new, qualitative studies.

“Advertisements often affect us at an unconscious level. Although many say that they ignore advertisements and that they do not purchase the advertised product here and now, advertisements aim to shape our own self-image. We need more knowledge on how and why this happens,” says Arnold.

According to the researcher and street artist, it is important to be critical to the way in which public-private partnerships and the zero tolerance policy restrict urban space.

“Commercial agents are powerful, and they obstruct other subversive practices from taking place. This affects not only the spread of graffiti and street art, it also restricts feminist and political visual and aesthetic expressions that may challenge established power structures,” says Emma Arnold.