Humans are tropical animals

Homo sapiens come from the tropics. That is why we create tropical microclimates in our homes, our cars and beneath layers of clothing. ,

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

It took a conference on Arctic issues to put tropical mankind on the agenda in the northern part of the world. The theme of the January 2014 Arctic Frontiers Conference in Tromsø, Norway was “Humans in the Arctic.”

Professor Hannu Rintamäki of Finland’s University of Oulu and the Finnish Institute of Occupational Health gave a presentation on work and well-being in frigid temperatures.

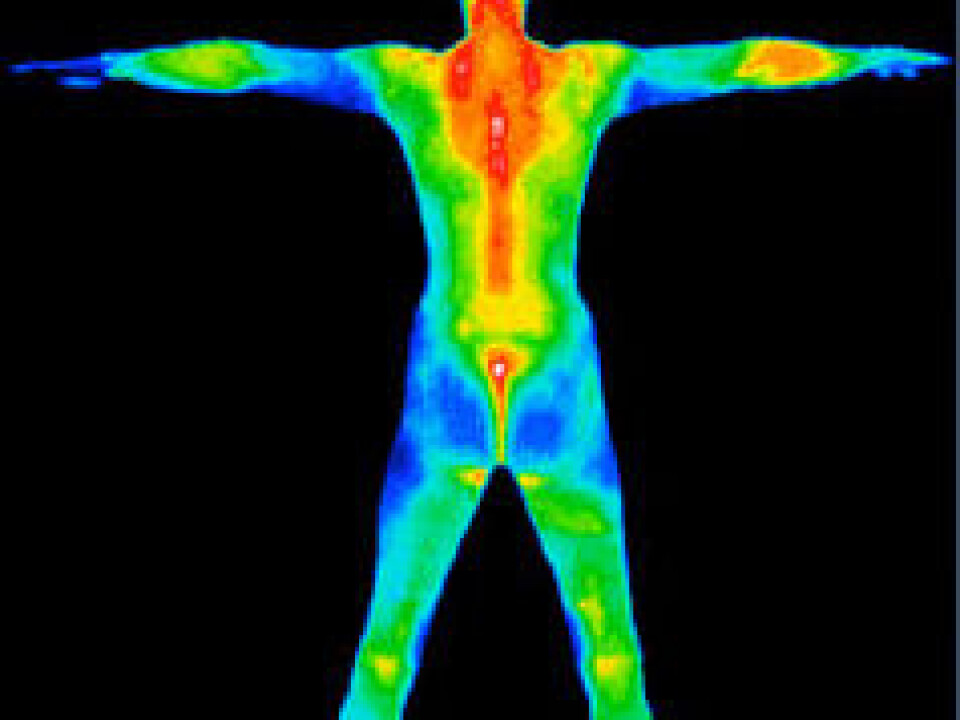

He depicted humankind’s comfort zones as follows.

To be comfortable in water, we require a water temperature of 33° C. Our optimal air temperature on land when at rest is 27° C.

The safest day temperature for people in the Mediterranean Region is 24° C, whereas the safest day temperature for Finns is 14° C.

The safe limit for working in the cold is -10° C, while to avoid hypothermia when sitting still without clothes for one hour, the temperature should not be lower than -1° C.

What Rintamäki designates as “thermal comfort” is linked to the origin of the species, to borrow Darwinian terminology.

“Humans come from the tropics,” the Finnish professor reminds us, which explains why we do what we can to maintain a tropical microclimate in our dwellings, at work, in cars and beneath our clothes when outdoors.

Even temperatures

He is eager to mention other ideal temperatures for maintaining comfort. We feel best when our core body temperatures are in the range of 36.5° C to 37.1°C when we are not in motion. If we are running or working out, our thermal comfort zone depends on the level of the exertion.

We feel best when the average temperature of our skin is from 32.5° to 35°C and when the difference between local body part skin temperatures differs by no more than 5°C.

The human body is at its best when it can regulate heat easily by adjusting blood flow – when we neither sweat to cool off nor shiver to warm up.

Apropos skin temperatures: While the ideal is 33°C, we begin to feel discomfort when temperatures climb over 35° or are under 31°C, and our performance starts to decrease when skin temperatures drop below 30° or rise above 35°. Our health is at risk when the surface temperatures of our bodies dip below 15°C or rise beyond 45°C. But remember, these are skin temperatures.

And bear in mind this information is from a conference in the Arctic, in January, where ambient temperatures can easily be on the low side of the comfort zone.

Weaker muscles

“But low skin temperatures are not the only stress factor. Continual changes in temperature are also troublesome,” says Rintamäki.

He has figures on why people in the Nordic countries might work less well outdoors in winter.

“As skin and the tissue below is cooled down, muscle power decreases by two percent per degree,” says Rintamäki. Arms and legs get cold most rapidly, and thin fingers are less capable than thick fingers at tackling the cold.

Good and cold

Not all cold is bothersome. Some types of cold increase well-being and comfort. A modest exposure will help you become more alert. A short exposure to extreme cold, such as ice-bathing, is an example.

The shock of icy water triggers the production of hormones such as endorphins and cortisol (hydrocortisone), and these make you relax afterwards.

When you work hard, exposure to cold makes the heat you generate less of an ordeal. The chilling of joints and muscles, for instance with ice bags, reduces pain and swelling.

All things come to an end, as do individual lives. The seasons have an impact on mortality rates.

February is normally the coldest month in Finland, but the month when most Finns die is December. Norway is a little different, as January is its deadliest month.

“This is because we have not yet adapted to cold at the beginning of winter,” explains Rintamäki.

————————-

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling