The king fought for the Norwegian constitution – and his son

Christian Frederick didn’t have the Norwegian people in mind when he defended their constitution. He wanted his own son to assume the throne, claims a researcher.

Christian Frederick had long dreamt of coming to Norway. In the winter of 1814 he finally got the chance. At 27 years old, he was asked by his cousin, Danish King Frederick VI, to save what remained of the Danish-Norwegian union.

Norway was about to slip out of Denmark’s grasp after 400 years. The superpower had lost Norway to Sweden in the Napoleonic Wars.

During that year the Danish prince, who briefly became King of Norway, fought doggedly for Norway to become more independent through a Norwegian constitution. Why did he reverse course so suddenly?

Law professor Ola Mestad at the University of Oslo argues that it was to maintain the right of succession.

“The Constitution wasn’t really his thing. But it was the only grounds he had for claiming the right to the Norwegian throne. So he had to stick to it if he wanted to save his son's right to the kingdom,” says Mestad, who led the large research project on the events of 1814 to coincide with the Norwegian Constitutional Bicentenary in 2014.

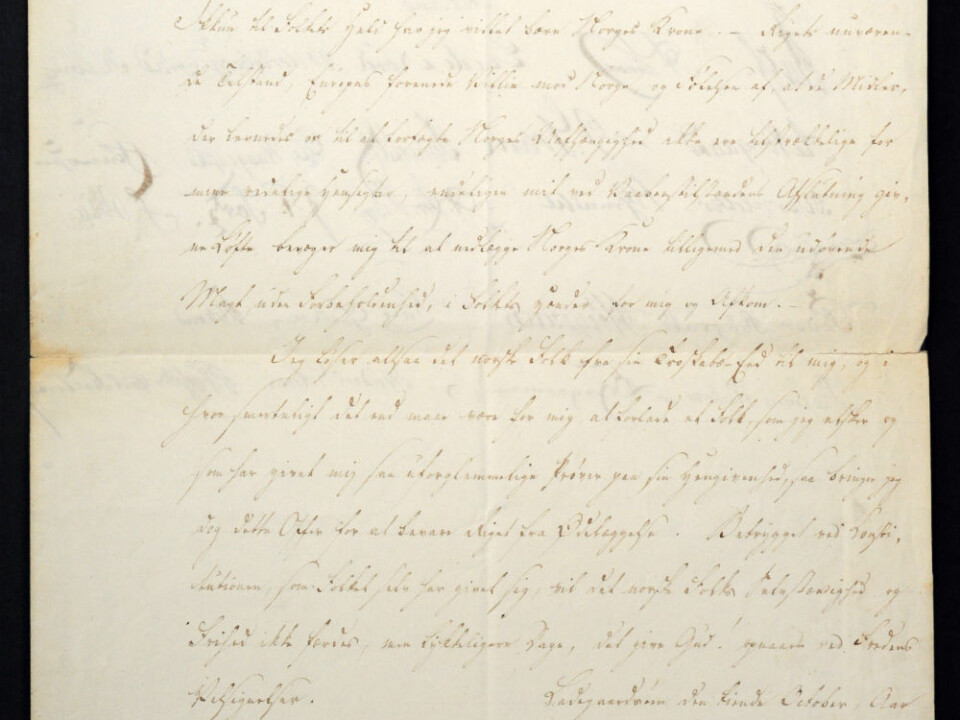

Secret coded letters

This is an entirely new interpretation of what happened in 1814. Historians have long wondered why Christian Frederick seemed to have changed his mind. Many believed that he got swept up in the atmosphere at Eidsvoll in the days up to 17 May.

Mestad has plumbed numerous historical sources to uncover the real motives.

Secret coded letters, diaries, newspapers and political reports are just a few of the puzzle pieces that together form a picture of the prince's enthusiasm for the Constitution.

Mestad has found what he thinks are clear indications that Christian Frederick fought for the Norwegian Constitution on behalf of his son:

• In his diary, Christian Frederick constantly wrote about the right of inheritance. He saw it as his mission to secure the throne when he came to Norway, writing, "It was my duty to myself and my kin – who sooner or later might come to claim their rights – to protest against Norway's surrender, since the King [of Denmark] had no right to give up his kinfolk’s inheritance." He also communicated this in a letter to his cousin, Danish King Frederick VI, writing, "Your Majesty can surrender the Kingdom but certainly cannot deprive your kin of their right of inheritance thereto."

• In a coded letter to Danish King Frederick VI, Christian Frederick mentioned his son: "If Norway’s throne is transferred to me, then I would assume it even were it on the edge of the abyss, just to secure for my son the right of inheritance to this Kingdom."

Reluctant abdication

• He made sure a picture of his son was hung at Eidsvoll when he was crowned King of Norway on 19 May 1814. During the ceremony, he reminded people of his successor to the Norwegian throne.

• As part of negotiations with the Swedes during the war in late summer 1814, he insisted that Sweden accept the Norwegian constitution in exchange for peace. The Constitution was instrumental in keeping the King on the throne.

• Christian Frederick realized with great disappointment that the battle for Norway was lost. In his own proposed abdication document, he tried to abdicate only on behalf of himself and refrained from mentioning descendants. This would enable his son to inherit the throne when the heirless Swedish King Charles XIII died.

• In the final abdication document "for me and my descendants” was added. The King added this against his wishes, according to the diary entry of parliamentary representative Søren Tybring, “I have it on good authority that he does not want to renounce his son’s succession to the throne and that he, when this was proposed to him, called out, "My God! Now Norway is demanding more of me than Sweden! However, the Norwegian wants it and it will happen.”

This substantial evidence suggests that Christian Frederick took it hard when he had to relinquish the throne not only for himself, but also on his son’s behalf.

Lousy warrior

Christian Frederick’s legacy has been mixed. On the one hand, he was a lousy warrior. On the other hand, he became a heroic champion of Norway’s nascent democracy.

However, his valiant battle for the Constitution was not governed by a desire for democracy, but for the monarchy, writes Mestad in an article in the Norwegian journal Historisk tidsskrift.

Mestad believes that he’s the first person to come up with this theory. It took a bit of detective work to get on the right track. Only when he called The National Archives of Norway did he find the final proof: a high-resolution photograph revealed that the king had changed the abdication document from the first draft.

Researchers who have studied 1814 have been particularly interested in the political work that happened in the spring. Mestad instead located documents from the autumn of that year.

He searched systematically for explanations of why the king had added a sentence to the abdication document. Suddenly it became clear to him that the King had added his son against his will.

“I was very pleased when that theory came to me,” says Mestad.

Heard it "at the club"

Finn Erhard Johannessen of the University of Oslo cannot recall having seen this explanation before.

“Now some pieces do fall into place” better, the history professor says.

“I’ve been sceptical of Christian Frederick for a long time. First he pushes himself onto the throne and then this aristocrat turns into a friend of the popular constitution? This sudden shift has always seemed a bit odd,” he says with satisfaction.

Johannessen thinks Mestad provides thorough documentation for his interpretation.

Mestad cannot know for sure that Christian Frederick had to relinquish his son’s right to the throne against his will. The sources that indicate this are the diaries of three people who knew it “on good authority” and who had heard it "at the club." The King's own diary is completely blank in this period.

“The best thing would obviously have been if Christian Frederick himself had said that this was terrible. But when multiple sources mention it independently, there’s reason to believe that it's true,” says Johannessen.

“Of course all three could have heard it from the same person, but it’s just as likely that they had different sources,” he says.

And context matches up, with a king who had long stated the plans he had for his son.

Flexible strategist

This reinterpretation of Christian Frederick reminds us that proponents of a cause can have widely different motives,” says Johannessen.

“The discovery doesn’t necessarily rock the picture of 1814. But it’s an interesting detail,” he says.

Mestad, for his part, thinks that this is important information because it says something about just how complex historical processes really are.

“It shows that no one person or group carries out their plan. Time and again stronger forces derail them,” he said.

The King was a flexible monarchist, more concerned with the royal house than the nation, says Mestad. He constantly changed tactics to suit his purposes.

The prince who came to Norway to secure a Danish-Norwegian throne was looking for continued autocracy at the start. With things changing so quickly in war-torn Europe at that time, it might not have been too much to hope for, even if the Swedish King had officially received the crown.

When he realized that in a pinch, he could secure the throne in a somewhat more independent Norway, he at first protested against parliament creating the constitution. He wanted to control and do it himself.

Eventually he realized that wouldn’t work, but he was promised that an independent Norwegian populace would choose him as king. He was very concerned about the provision that the king had to be elected by the people, because this was the only way he could safeguard his position when the Swedes came knocking.

Vying for the throne

Christian Frederick managed to climb his way to Norway’s throne. But his power didn’t last long.

The summer brought war between Norway and Sweden. Although the Swedes had officially defeated Norway, they had to come and take the country. The Norwegians were provoking a conflict, headed by their newly elected king. But Christian Frederick gave up easily. Was he a coward?

Mestad maintains he was actually quite tricky, explaining, “Sweden’s used up its money and can’t afford to fight much longer. He’s about to come to an agreement with the Swedes that they accept the Norwegian Constitution in exchange for power over Norway. So he can’t fritter it all away by continuing to fight.”

With throne rule changing all the time, ongoing wars and fragile peaces, no one could know how long the Swedes would be in charge.

“So it might be smart to think, ‘Should I put in for an inheritance share?’” says Mestad.

In a secret, coded letter to Danish King Frederick VI, Christian Frederick – even before he was crowned – wrote that "the Swedish dynasty won’t hold out a generation." He envisioned that Danes could regain the throne if his son held the right to succession when the heirless Swedish King Charles XIII died.

At this point, he was thinking primarily of his son, and "that he, if Norway is conquered again sometime, will sit on Norway’s throne, I have no doubt."

“Christian Frederick wasn’t a stupid man. Many people think that it was a little naive to be crowned king given the tenuous situation Norway was in then. But he was thinking ahead,” says Mestad.

Shattered dreams

So up to that point Christian Frederick still had prospects for his son to assume the throne sometime in the future. But the hidden plan backfired.

The final defeat came on 10 October 1814. Paradoxically, it was Norway’s parliament, Stortinget – which he had so far relied on – that forced him to write his son into the abdication document. By autumn they had all grown tired of the Dane.

His dream was shattered. It’s said that the outgoing King was so moved that he had to go in to his cabinet when he was about to bid farewell to the Norwegians. But Mestad asserts that he was probably not primarily upset because he had to leave the country.

“It’s no wonder he was tearful when the whole idea to secure the throne for his son went up in smoke, he said.

“Why he was in tears, none of us can know,” says Johannessen, who thinks Mestad is stretching his interpretation a bit far on this.

“If I’d been king, I’d have been just as sad to think that I wouldn’t be king any longer,” Johannessen says.

Christian Frederick was a sensitive man. He had dreamt about coming to Norway, to accomplish something big.

And that he did. Regardless of his intentions, today Norwegians can thank him for his tireless struggle to create the Norwegian Constitution.

--------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no