The blanket that won an award from Queen Victoria and ended up on the Paris catwalk

Berger wool factory made fairly ordinary blankets, until two bold moves changed everything.

A frozen Oslofjord marked the beginning of an industrial adventure in the small village of Berger a little farther south.

In 1879, factory owner Jürg Jebsen and his son Jens were on their way to Oslo. Jebsen already ran a wool factory on the west coast, but they were scouting opportunities for a new factory aimed at the larger markets in Eastern Norway and in Sweden.

Thick ice forced Jürg and Jens to go ashore in the outer Oslofjord. From there, they continued by horse and sleigh. They arrived at Berger and saw the potential there. And when they met a widow who owned the water rights to the Berger River, they seized the opportunity.

"They may have felt at home here, because the landscape is a bit like the west coast, with its fjords and mountains," says Hanne Synnøve Østerud. She is a curator at Berger Museum, which is part of the Vestfold Museums.

This became the start of the Berger textile factory in 1880.

Built an entire community

The father, Jürg, brought expertise and some capital, but it was the 21-year-old Jens who built and ran the factory.

As with many industrial ventures of the time, Jebsen had to bring in expertise from abroad. England had the necessary machinery and know-how. People also came from Western Norway to work in the new factory.

Immigrants and newcomers needed a place to live.

"At the time, Berger was home to just a few farms, so Jens Jebsen built a new community with workers' housing, a church, and a school," says Østerud.

Two decisions that changed everything

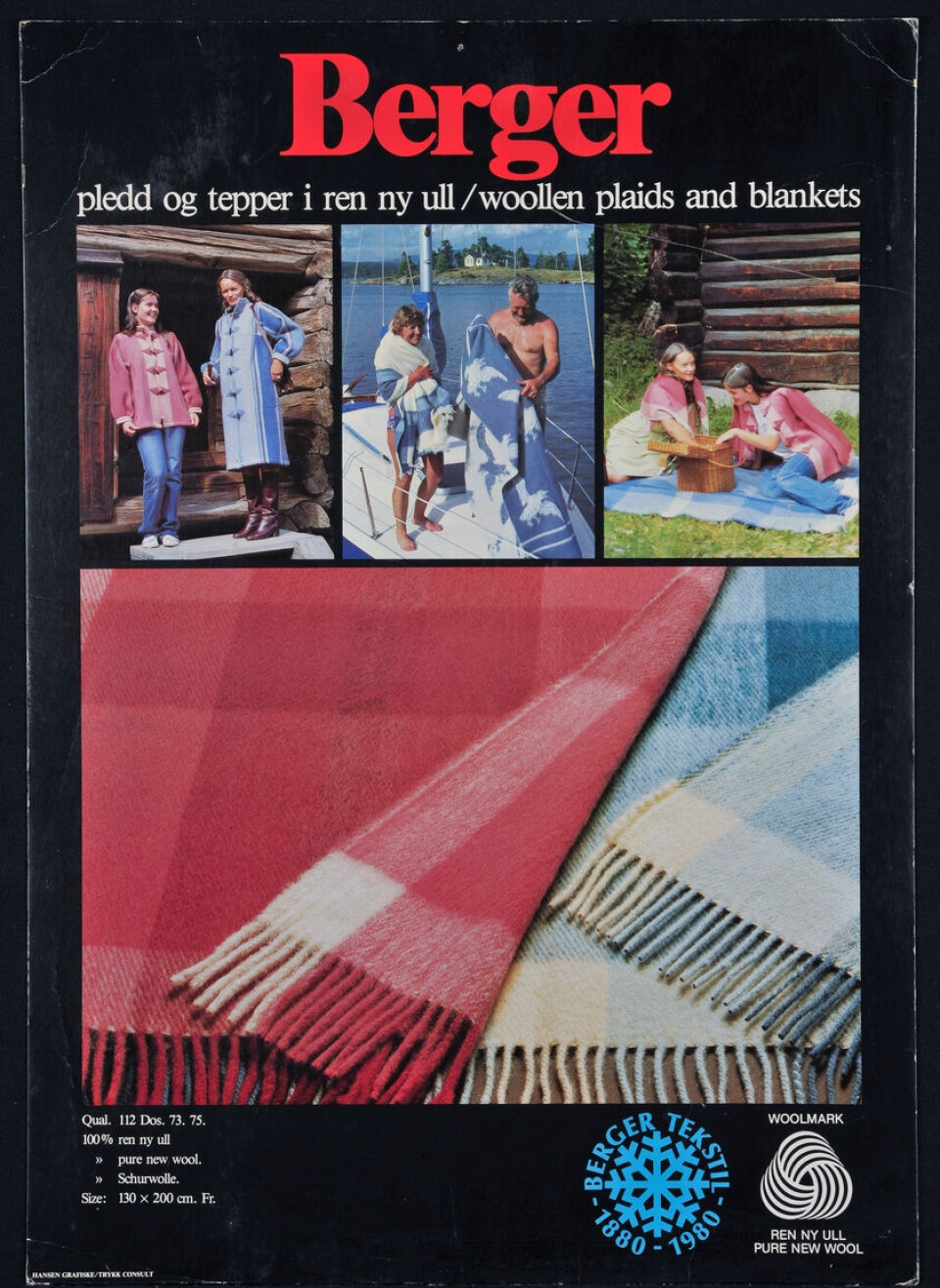

Berger Factory began like most wool producers of its era, making fabric for furniture, clothing, and wool blankets using standard methods.

Then Jebsen took two bold steps that would make his blankets famous both in Norway and abroad.

The first was adopting a weaving technique invented by a French mechanic in 1799. Just two years later, Jebsen bought a Jacquard loom, where a series of punched cards controlled the weaving patterns. The blankets became twice as thick, with more intricate designs.

Berger’s operations were truly global. The technique was French, the machines were English, the patterns and punched cards came from German studios. The wool was sourced from global markets, such as lamb's wool from New Zealand. The workers came from England, Germany, Sweden, and Norway.

Business was good. The blankets were sold to fabric stores, wholesalers, private customers, shipping companies, and nursing homes.

At a world exhibition in Liverpool in 1886, Berger factory received a medal for outstanding wool products from none other than Queen Victoria.

The second big step was bringing in a Norwegian artist.

Flying seagulls, leaping cod

In 1913, Berger commissioned artist Thorleif Holmboe to create new blanket designs.

"Holmboe was best known for his paintings, but he had also designed silverware and porcelain featuring motifs from Norwegian nature," says Østerud.

The commission coincided with the 100th anniversary of Norway's Constitution. At a large exhibition at Frogner in Oslo, the new blankets were unveiled: seagulls with a border of leaping cod, polar bears with walruses, and reindeer with owls.

The new patterns became popular. Car companies, shipping companies, and the Norwegian railway NSB all wanted them customised with their own logos.

Passengers on the the express boat Hurtigruten were wrapped in these blankets to stay warm when the air on deck turned chilly.

When asked by Science Norway to name a personal favourite at the museum, Hanne Synnøve Østerud points to these Holmboe creations.

"They're so beautiful, have had such a long lifespan, and are still used today," she says.

Saving the business with the Berger blanket

By the 1950s, Norway's textile industry was in deep crisis. Many factories closed down.

"With the introduction of free import, Norwegian companies could no longer compete with foreign goods. Berger factory also came close to bankruptcy, but survived by ending all other fabric production and focusing solely on blankets. They managed to build a brand," says Østerud.

This was the moment the Berger blanket once again became a household name across Norway.

A French marquis appears

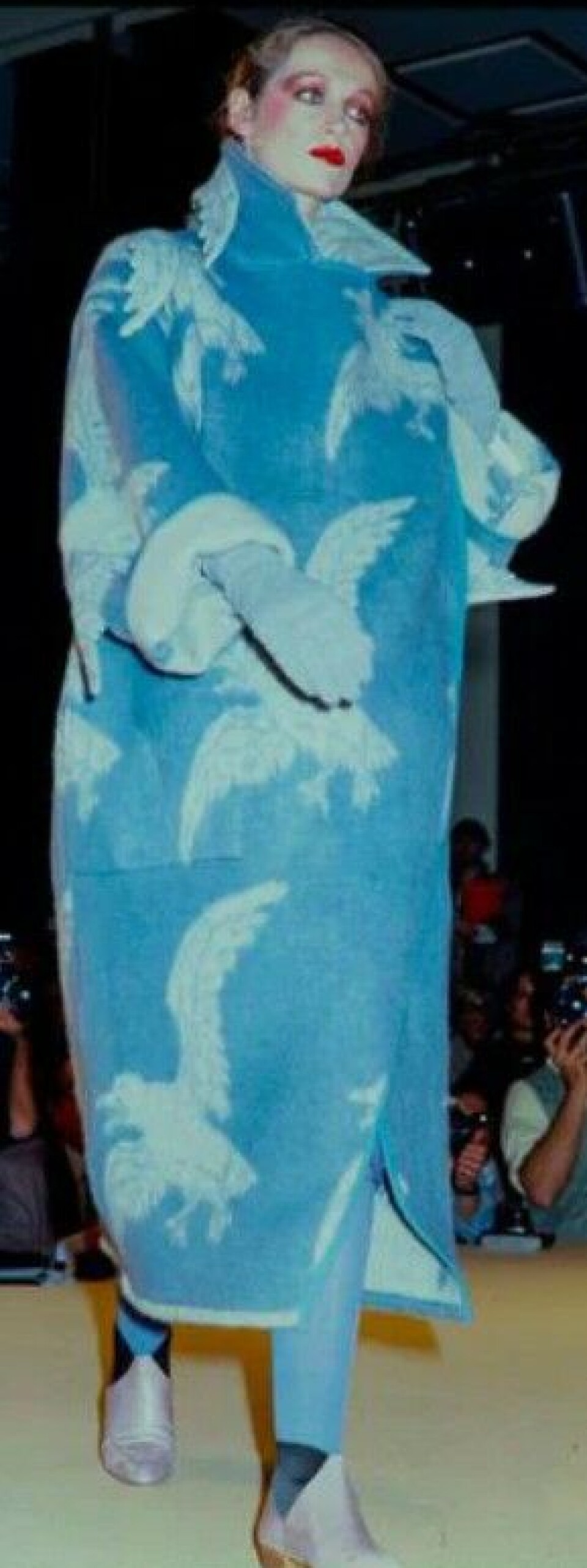

In the early 1980s, Berger blankets gained international recognition – thanks to a French nobleman.

"Marquis Jean-Charles de Castelbajac showed up here in the dead of winter, barefoot in moccasins. People were quite shocked," says Østerud.

The marquis was a well-known fashion designer. He immediately fell in love with Holmboe’s patterns and Berger’s fabrics.

"In 1982, the seagull hit the catwalk in Paris. A tall model with heavily teased hair wore a blanket coat covered in seagulls. One of the wings was designed to stick out from the oversized shoulder pads that were fashionable at the time," says Østerud.

"Four years later, it was the polar bear's turn," he says.

Celebrity fashion

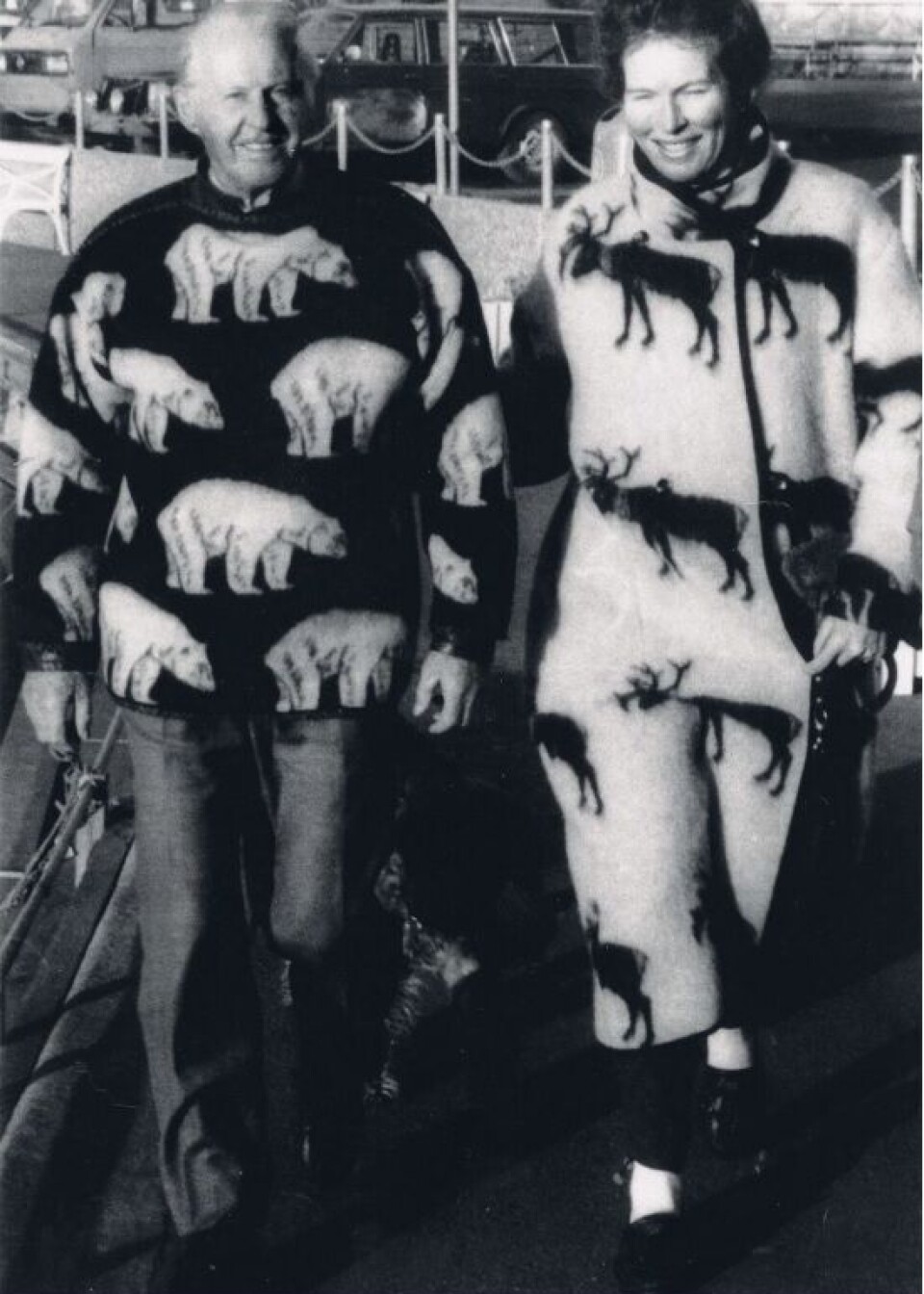

Unn Søiland Dale, the designer behind the iconic Marius sweaters, followed the marquis' lead and created coats, jackets, and hats using Holmboe's patterns and Berger's blanket fabric. In the USA, vests and jackets decorated with seagulls and polar bears became especially popular.

"Film star Bo Derek, Queen Sonja of Norway, and Thor Heyerdahl all wore these jackets and coats," says Østerud.

"Thorleif Holmboe's patterns have been produced since 1913. They're incredibly beautiful and still alive today. If you're lucky, you might come across pieces for sale in second-hand shops or online," says Østerud.

Then it ended

Running a textile factory in Norway proved difficult. In 2003, the Berger factory closed, and production moved to Latvia.

At the time, Hanne Synnøve Østerud worked at the Nord-Jarlsberg Museums, later the Vestfold Museums. She brought in a film team to document the final days.

"Along with the last factory owner from the Jebsen family, Jørg Jebsen, we documented the business and filmed the final production. It included a major order of blankets for the airline Braathen Safe and fabric by the meter with Holmboe’s designs," she says.

Most viewed

The old Berger factory now lies abandoned and overgrown. Directly opposite lies the Fossekleven factory, built in 1889. It produced textiles until 1963 and was run by Jens Jebsen’s brother.

The old factory now houses the Berger Museum and Fossekleiva Cultural Centre, where artists work and exhibit.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

Related content:

Subscribe to our newsletter

The latest news from Science Norway, sent twice a week and completely free.