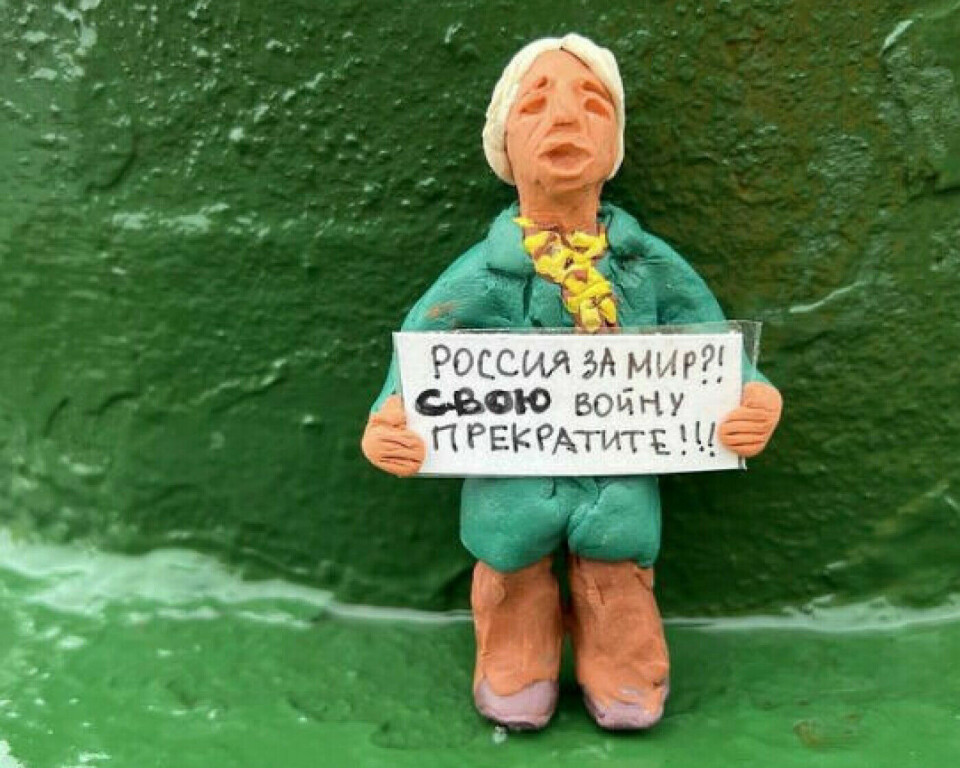

This little doll allows Russians to silently express their resistance to the war

People place little dolls with anti-war messages in squares in big Russian cities. The Russian war resistance lives on, researchers say.

Today, a Russian can get 15 years in prison for standing up in a square and protesting against the war. But a little doll cannot be put in prison.

“We know there is a lot of support for the war, but there is also opposition. It can be difficult to recognise and understand this resistance because it’s nearly invisible,” Kari Aga Myklebost says. She is a professor at UiT The Arctic University of Norway.

There is a lot of fear in Russia now. As a result, the protests are small, but still significant, believe researchers who study the Russian resistance to the war.

A new form of war resistance

There are no demonstrations against the war in the streets of Moscow, St. Petersburg, Yekaterinburg, and the other big Russian cities. But there are creative anti-war protests in these cities, according to Katrine Stevnhøj. She is a researcher at the University of Copenhagen, where she is writing her doctorate on the Russian war resistance.

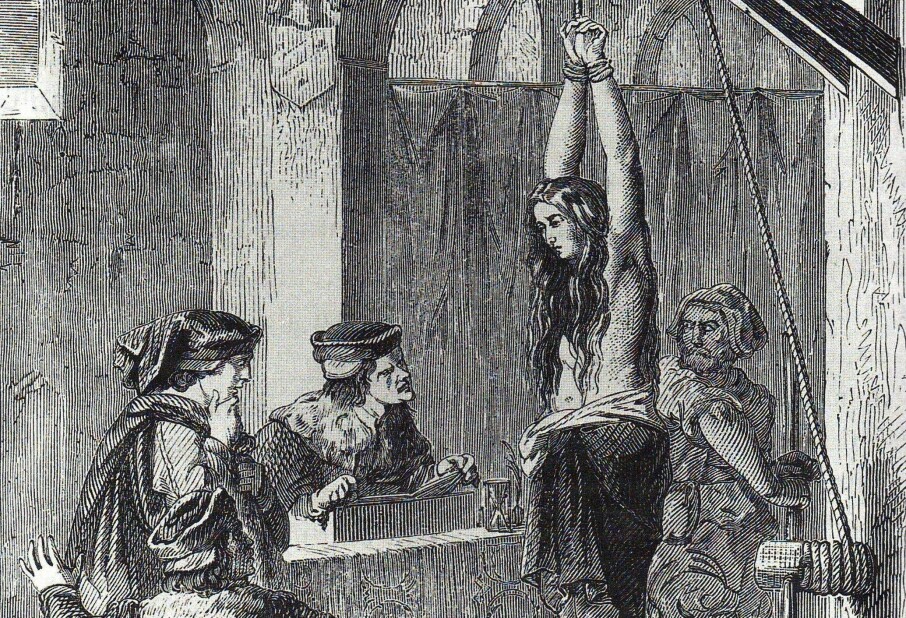

When the invasion happened in February last year, people held signs protesting the war. This is now far too dangerous. That is why small dolls are being placed around town squares. These dolls carry posters with anti-war messages.

Important, small protests

Even though these symbols don’t change the distribution of power in Russia, they are important protests, Stevnhøj believes.

They show the outside world that some Russians oppose the war.

It also makes it clear to people living in Russia that there are at least some people who are against the regime.

Most viewed

Strict laws

In March 2022, Russia passed a law that allows for a sentence of up to 15 years in prison for people who spread ‘false information’ about the hostilities. In practice, false information means anything that goes against what the authorities say.

There was camera surveillance in public places, such as on buses and the metro. The police sought out people who had attended demonstrations afterwards, based on facial recognition.

Nearly 20,000 people have been arrested for protesting against the war since February 2022, according to the organisation OVD-Info, a monitoring and advocacy group for human rights in Russia, which keeps track of this information. More than 800 people have been prosecuted.

Most were arrested in the first four weeks after the war started, before the new legislation was introduced.

Seven years in prison

People have mostly been scared into silence. But not all.

One woman who dared to protest was 33-year-old Aleksandra Skotshilenko. She was sentenced to seven years in prison in November for swapping out price tags in a grocery store with critical information about the war.

The punishment for her is equivalent of the death penalty, her mother says. Skotshilenko suffers from celiac disease, according the Russian website MediaZone.

The last word

Another example of resistance are the speeches given in court cases. The accused is given the opportunity to say ‘one last word’.

“This is the last bastion for freedom of speech in Russia,” Stevnhøj says.

Aleksandra Skotshilenko took advantage of this opportunity before her verdict was handed down. She made a long speech addressed to the judge:

“Everyone sees and knows that you are not judging a terrorist. You’re not judging an extremist. You’re not even judging a political activist. You are judging a pacifist,” she told the judge, according to an article in the Norwegian national newspaper Aftenposten.

She continued:

“Despite the fact that I am behind bars, I am freer than you. At least I'm not afraid to say what I think.”

A national funeral

It was also a shock for many Russians when Ukraine was invaded in February last year. Some experienced it as deeply sorrowful and described it as a national funeral and a loss of dreams and hopes for the future, Stuvøy explains.

She is a professor at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences (NMBU) and conducts digital interviews with Russians about their lives after the war started.

She also sees that war resistance has become part of everyday life for Russians.

“There are a number of small protests in everyday life, such as creating graffiti, laying flowers at memorials to the Ukrainian artist Taras Shevchenko, wearing rainbow bracelets or other symbols,” she says.

Shevchenko is considered by many to be Ukraine's national poet.

Leave or stay?

Today, Russians who still live in the country are constantly assessing whether they should stay or leave, Stuvøy explains.

“Being prepared to leave is an important topic of conversation. What will they do about their job? How will they relate to family and friends if they leave?” she says.

Leaving is also about abandoning culture and memories.

Staying also poses many dilemmas. The war creates new moral, social, and political divisions in the Russian wartime society, she says.

“People who want to talk about the war have to navigate a tricky situation and figure out who they can talk to about these things, both when it comes to their family and at work. Some people avoid talking about the war because of disagreements. Some find alternative social spaces, such as book or film clubs, to talk about the war and what it does to them,” she says.

Some choose to leave

Many have left Russia. But there are only a few Russians who have the resources and dare to make that choice, Kari Aga Myklebost believes. She primarily studies Russian journalists who work in exile.

One group that has largely chosen to leave Russia are journalists. They can no longer do their job in a meaningful way in their homeland.

“It’s not an easy choice, but they do it because they have to. This is due to the Kremlin's strong grip on the Russian public and military censorship,” Myklebost says.

Will present the facts

Before the war, Russian independent journalists were activists – it was necessary to fight back against Russian official propaganda, Myklebost believes.

There is still a lot of activism in this professional group. But it is also important for these journalists, who are now based in Vilnius, Riga, Berlin, Prague, and Amsterdam, to maintain a basic level of professionalism, she explains.

“The journalists are committed to showing that they are not participating in an information war, but are engaged in professional and objective journalism based on facts. That’s contrary to what the Kremlin is doing,” she says.

Breaking through the censorship wall imposed by Roskomnadzor, the Russian federal agency responsible for monitoring, controlling, and censoring Russian media, and reaching a Russian audience with independent reporting from the war in Ukraine is a hugely important anti-war effort by Russian journalists in exile, she believes.

Russian journalists in Norway

In Norway, too, there are Russian journalists who work in exile.

The Barents Observer newspaper, which is based in Kirkenes, on the Russian border, employs four Russian journalists in exile. They deliver news in both English and Russian.

These exiled journalists systematically report on the war resistance in Russia and on the negative consequences of the war for Russian society.

“Quite a lot of Russians see and understand what is happening in Ukraine,” says Myklebost.

But the threshold for open war resistance has become very high. Most people do not dare to protest, they are afraid of being sentenced to 15 years in prison, but still criticise the war indirectly, she explains.

“In the comment sections on social media, we see that many people are critical of the country’s economic and political priorities. They don’t use the word war in these comments, but write about decaying schools, hospitals without medicine, public infrastructure that is completely destroyed. These are not priorities because the Kremlin chooses to use the money for war,” she says.

———

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no