Precise dating from Medieval Oslo: This is undoubtedly the King's Wharf

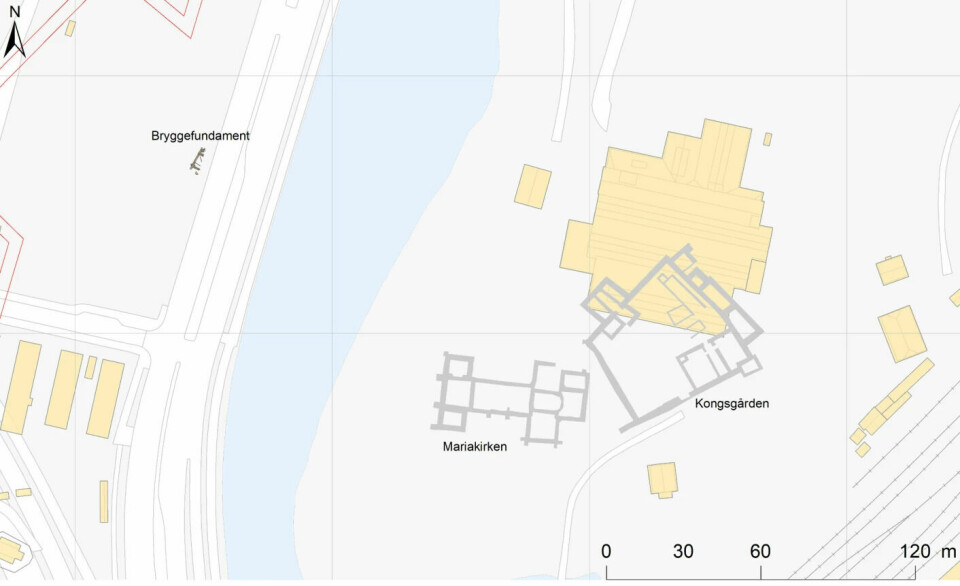

The King’s Wharf, which was excavated in Bjørvika earlier this year, was built with trees felled in 1288.

In March this year, archaeologists from the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research (NIKU) found eight metres of intact wharf foundation, which they they assumed was the King's Wharf from medieval times in Oslo.

Like so much other timber excavated from the Middle Ages, the King's Wharf also ended up in the rubbish heap – but not before the archaeologists had secured a lot of sample material.

When parts of the same wharf were excavated in the 1990s, it was not possible to date the wood.

The historical tree ring data required for dating wood through dendrochronological analysis was insufficient back then.

Now, the archaeologists have the answer and can confirm that the wharf was built from logs felled in the winter of 1287 and spring of 1288.

Two lines under the answer

“We were a bit doubtful about when it was from, but it turns out that it’s from the oldest range of what we thought was possible,” Håvard Hegdal says.

He is an archaeologist at NIKU and project manager for the excavation where the King's Wharf was found.

“It's lovely to get such clear answers like this; the dating is crystal clear,” he says.

Significant efforts have been made to enhance the historical curves of tree rings since the wharf was last exposed.

“The more timber like this we excavate, the better foundation we have. Constructing these curves is a massive undertaking,” Hegdal explains.

"Researchers have been systematically working for nearly 100 years to collect and assemble samples of tree rings, both from new trees and from several thousand-year-old logs pulled from bogs. Every time we submit samples for dating, we contribute to building a better database for this research."

The wharf of King Haakon V

The wharf extended in a straight line from what was the royal estate in Oslo at that time. The royal estate was given to St. Mary’s Church in 1319, any dating after this year would indicate that it had no connection to the King.

“But now we know for sure that it is indeed the King's Wharf,” Hegdal confirms. “Or perhaps rather the Duke's Wharf?”

In 1288, Eirik II Magnusson was the king of Norway, with his main seat in Bergen. His brother, Duke Haakon, ruled in Oslo. When Eirik died in 1299, Haakon V succeeded as king for all of Norway.

Haakon V is known for making Oslo the capital of the kingdom in 1314 and for building the fortress on Akersneset, where Akershus Fortress stands today.

He must therefore also have been behind the construction of the King’s Wharf.

Short lifespan

But the wharf was not necessarily used for long.

“It was definitely out of use by the end of the 14th century, because we found a large anchor right in the middle of it. If boats are dropping their anchors there, then it’s no longer a wharf,” Hegdal explains.

Inside the wharf, the archaeologists found a rubbish dump.

“There was an accumulation of fish waste, faeces, and dirt. We found fungi preserved in the dirt, which break down wood,” he says.

Most viewed

The archaeologists' next project is to try to determine exactly when the King's Wharf became a rubbish dump. They will do this by compiling a series of uncertain carbon datings of the material, which together could provide a fairly accurate dating.

“We hope to pinpoint the exactly when the wharf was abandoned,” Hegdal says.

Doesn't change history

“It's about what they had estimated,” Axel Christophersen comments regarding the dating.

He is an archaeologist at NTNU.

“That it has been dated so precisely can be interesting in itself, but it doesn't change world history, nor the history of Oslo,” he says.

And at the same time:

“It’s obviously interesting and fun for those who hold the history of Oslo as part of their identity. Then it is clearly important that it’s not just any wharf, but specifically the King's Wharf,” he says.

Additionally, understanding that it was the King's Wharf can provide greater insight into why it was constructed in that particular manner and with those specific materials.

The logs that were unearthed in Bjørvika were larger than any they had found before, NIKU's Håvard Hegdal reported earlier this year.

“The King’s Wharf seems to be much larger than they initially thought, and this might not be solely due to functional needs. There could be symbolic meanings there that we might overlook unless we consider it as a part of the royal estate,” Christophersen says.

“The ideology behind a royal estate, beyond accommodating several hundred people, was fundamentally about symbolically representing the King's presence in the city."

Just another tragic example

There should be an improved system to ensure preservation funds accompany excavation projects, said Stine Torbergsen of Medieval Oslo in the Council for Cultural Affairs, following a report by forskning.no wrote in May that the King's Wharf was not preserved (link in Norwegian).

According to Christophersen, there is nothing special about the story of a great find being destroyed. The oldest remains of the wharf in Bergen were excavated in the 1950s and 60s, well-preserved, documented – and then destroyed.

“In Trondheim, we have examined and documented around 250 townhouses or buildings. None of them have been preserved, despite being among Norway's oldest physical structures,” he says.

He believes it would have been remarkable to have the discovered section of the King's Wharf displayed in a museum, considering the potential of such a physical structure to convey the history of Oslo's harbour and its urban community during the Middle Ages.

"I've been similarly involved here in Trondheim, where we've had excavations as extensive as those in Oslo. We've also been keen on establishing a medieval museum, but such efforts are futile if they are considered only as an afterthought," Christophersen says.

“The fact that the King's Wharf in Oslo has also been destroyed is just another example of the incredibly many other sad destructions that have taken place in Norwegian urban archaeology since the beginning of the last century. Politicians fundamentally bear the responsibility for this.”

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik.

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no