Pigs provided food in the Middle Ages, but men had to watch out for their scrotums

It was quite common to have a pig in your backyard in Europe's medieval towns. But there were fines if it was allowed to roam freely, or if it bit off someone's scrotum while that person was using the outhouse.

Archaeological findings from the Middle Ages indicate that the meat most commonly eaten by people came from cows. In second place were sheep and goats.

The lowly pig came in at third place.

But the pig's place in society during the Middle Ages is underestimated, Dolly Jørgensen believes. She is a professor of history at the University of Stavanger.

When she wrote her master's thesis many years ago on forestry around the year 1100, she discovered that pigs grazing in the forest were an integral part of forest management. And when she was working on her doctorate on cleanliness in medieval cities, she came across an entire set of regulations on how to keep pigs in the city.

“For many years I have thought that the pig needs a complete story,” Jørgensen says.

The book detailing the role of pigs in the Middle Ages is set to be released soon, more specifically this upcoming spring.

Pigs in the backyard

Most viewed

Jørgensen has trawled through historical legislation and legal documents, property transactions, religious texts, archaeological materials, medieval manuscripts, and art in her search for pigs.

The history spans all of Europe, mostly Western Europe, from around 500-1500 AD.

“There are many pigs in Norway today, people eat pork all the time: ham, bacon, and sausages. But we don't see them, and we don't think about them,” Jørgensen says.

During the Middle Ages, it wasn't like that.

"At that time, everyone was quite well acquainted with pigs. Both as living animals and as food. They were a completely normal part of life, not only in the countryside, but also in the city,” she says.

In several of the towns for which Jørgensen has found data, a third of the inhabitants had pigs. They usually lived in a pigsty in the backyard.

“Pigs are very flexible animals, they are happy to eat your leftovers,” she says.

Both beer brewers and bakers wanted to have a pig or two as a sort of rubbish disposal – the pigs ate the waste from production. Several cities, however, had laws that you could not give pigs the remains of other animals.

Regulated by law

Many cities employed pig herders who were paid to take the pigs outside the city walls and into the woods to eat nuts and mushrooms, or out into the fields to eat leftovers after the harvest.

In the city, however, pigs were not allowed to roam free.

“Pigs can be very aggressive if they're hungry, and they will eat whatever they want,” Jørgensen says.

A story from France even describes a pig that ate an infant.

“We don't know if it actually happened. But there was good reason for why pigs were not allowed to be loose in the city. Most of the cities I've looked at had regulations stating that the pigs had to be in the house or in the backyard. If they were to leave these enclosures, it had to be with a shepherd,” she says.

People who did not follow the rules were fined.

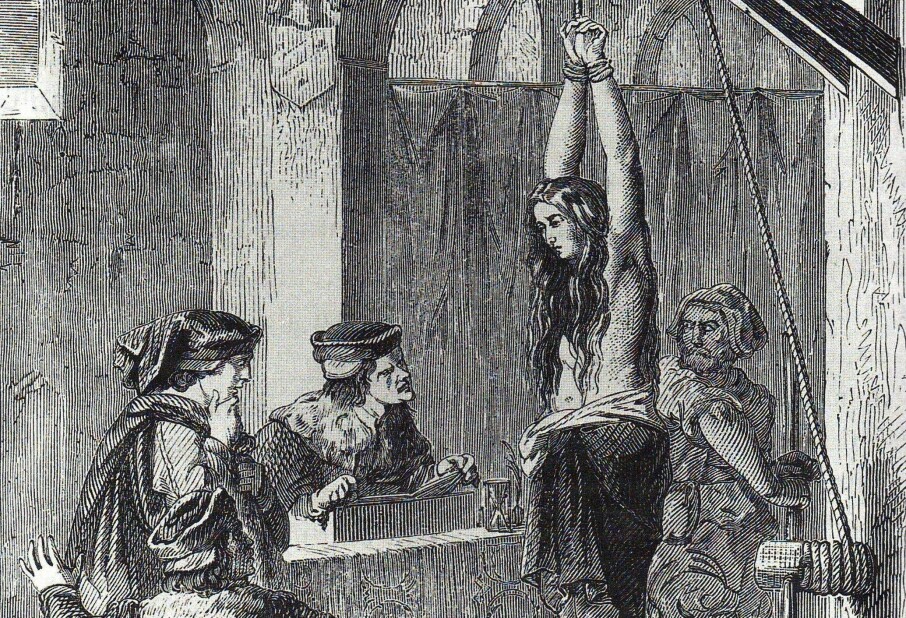

The fact that pigs were part of city life is also illustrated by stories of the outhouses of that time.

During the Middle Ages, an outhouse could consist of a pole to sit on that protruded from the wall.

But it wasn't necessarily just a matter of setting up such a pole anywhere. Magnus Eriksson's national law in Sweden specified the correct height for the bar. If the pole was placed too low, the property owner could be liable for compensation if a pig bit off the user's scrotum.

Dispensation for hospital pigs

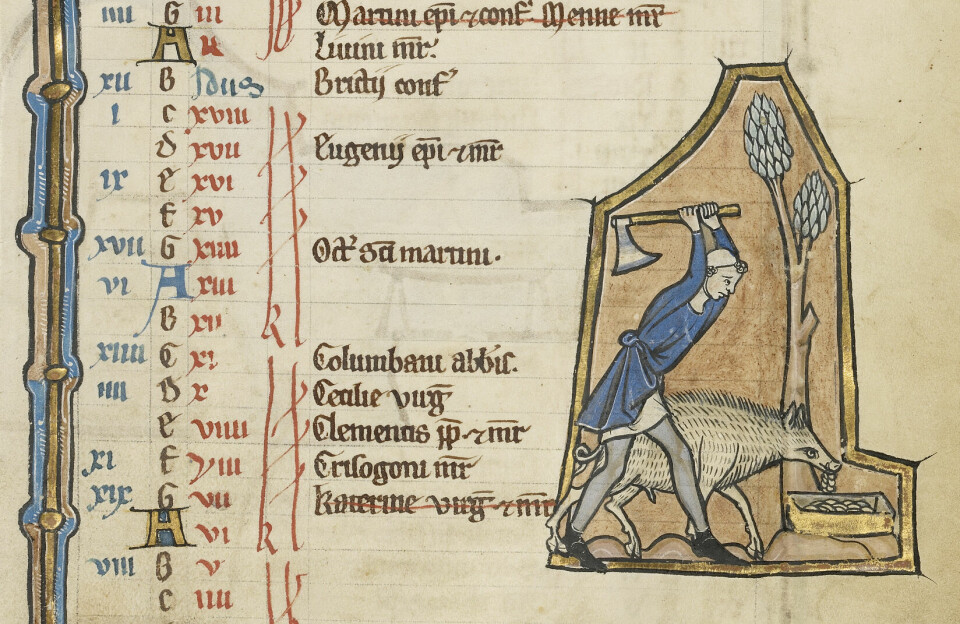

Jørgensen has found many images of pigs in calendars of the church's holy days. October often had a picture of pigs out in the forest to signal that this was the time to take the animals out into the forest to eat acorns. In December, there were often pictures of pigs being slaughtered.

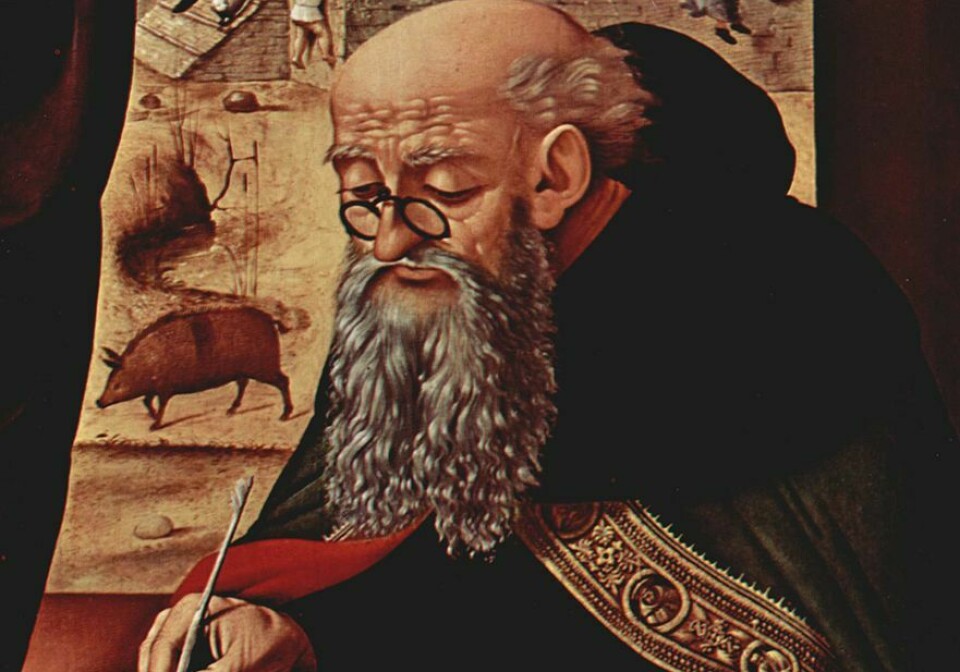

Another example from the world of art is found in paintings of Saint Anthony the Great. The man who is often considered the first monk is commonly depicted with a pig. There are many different stories as to why St. Anthony is accompanied by this pig. One explanation is that it is related to the Hospital Brothers of Saint Anthony, established as an order in 1095.

The Hospital Brothers established monasteries and hospitals across Europe and received dispensation from the Pope to let their pigs roam freely in the streets of medieval cities.

“But the pigs then had to wear bells, just like a sheep or cow wears a bell,” Jørgensen says.

The pigs and pig fat were important as food and treatment in the hospitals. This is most likely also the reason why St. Anthony is portrayed with a pig wearing a bell around its neck, according to Jørgensen. St. Anthony eventually became the patron saint of livestock, especially pigs.

Dirty pigs

The pig also appears in the realm of thoughts and ideas.

“Pigs tend to eat too much. When you talk about a person who has a tendency to overindulge, that person is called a pig,” Jørgensen says. “Pigs also like to roll around in mud puddles, because it's actually good for their skin. But most people think this means they are dirty and that it’s a bad character trait.”

There was also a female saint who was a pig herder and who symbolised loyalty and the value of doing one's job well.

“But for the most part, the ideas associated with pigs are negative. They eat too much, they have too much sex and have too many offspring, and they are dirty,” she says.

Animal bones are hardly ever collected

“It sounds absolutely fantastic that there is a book about the role of the pig in the Middle Ages!” Tone Bergland exclaims. She is an archaeologist at the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research (NIKU).

Bergland is an expert on animal bones and makes sure that relevant animal remains are not just tossed away during excavations.

“You collect so many exciting finds, jars and combs and all sorts of other objects. But animals, which have been so extremely important to people, are hardly ever collected,” she says.

That’s true even though animal bones make up a very large part of the material found from the Middle Ages.

“We get super exciting results from the little we find, but there's rarely room in the budgets to analyse everything,” Bergland says.

Pig farming in Oslo?

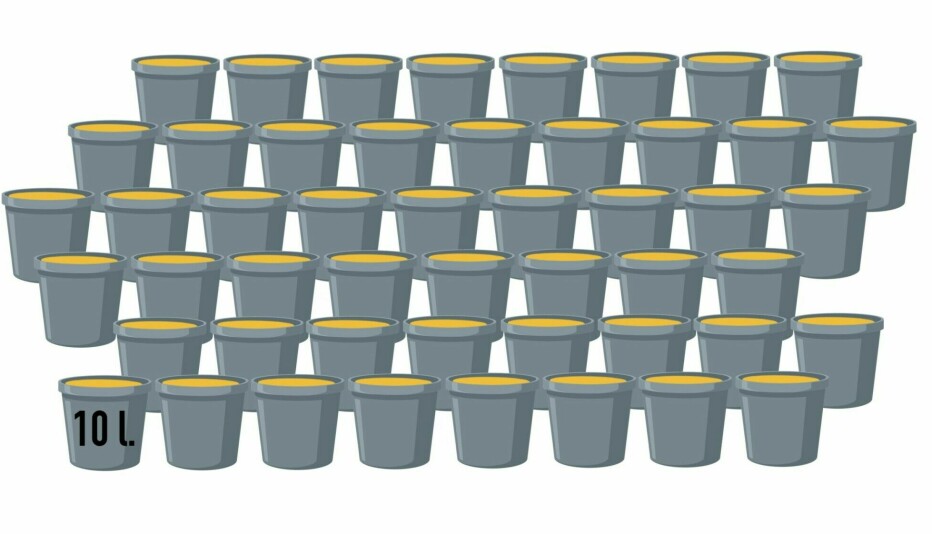

When Bergland recently participated in an excavation in the the Medieval Park in Oslo, archaeologists uncovered an area where there seemed to be more pigs than elsewhere in the city.

“It's a small sample that was collected, but we can still detect certain patterns,” Bergland says.

The pattern was different from the rest of Oslo and the other large medieval cities.

Usually, pigs make up around 10-20 per cent of the animal bones that archaeologists find. But in the Medieval Park, pigs accounted for up to 30 per cent of the material. The archaeologists also found many piglets.

“That made us think that some form of breeding has probably been carried out on the site. Stillborn piglets were discarded; they weren't eaten either," Bergland says.

The archaeologists can also see that the pigs were slaughtered before they grew too big. Many were under one and a half years old.

“This means that they have had a surplus of pigs in the area. They didn't have to conserve the pigs and continuously expand the population but could slaughter them when they reached the perfect weight for slaughtering,” Bergland says.

———

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no