No one really knows where the lion's mane jellyfish comes from

Researchers have still not managed to find the tiny polyps that produce these jellyfish.

"We still haven't found them out in the wild," Tone Falkenhaug tells Science Norway.

She is a researcher at the Institute of Marine Research and an expert on jellyfish.

If you’ve ever spent time by the Norwegian coast, you’ve seen lion’s mane jellyfish.

At times there are so many in one spot that it’s nearly impossible to dip a toe in the water.

But exactly where they originate in the wild, no one can say for certain. So far, no definite findings have been made, according to Falkenhaug.

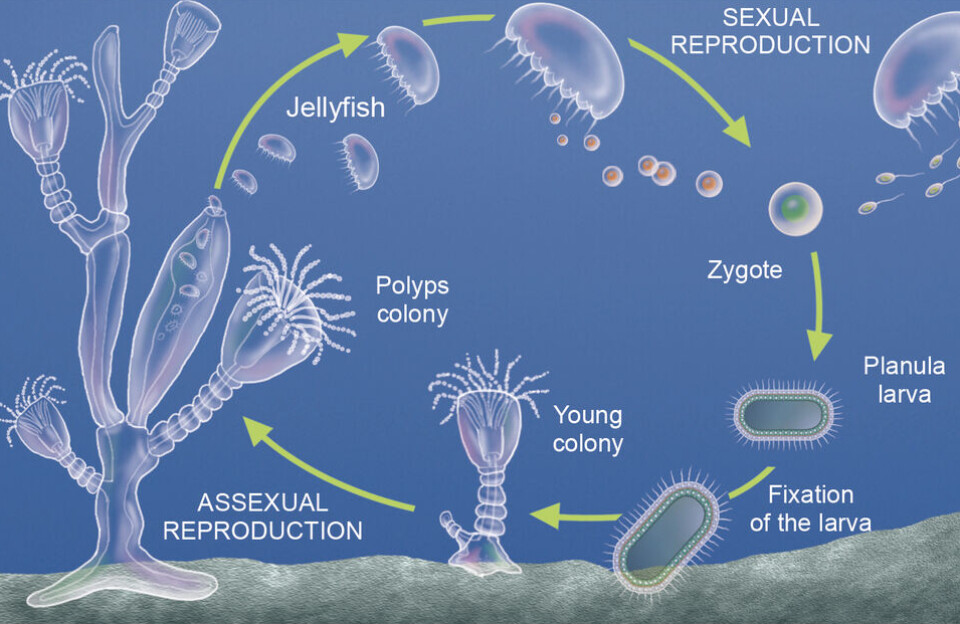

"They reproduce in an incredibly complex way," she says.

And one of the many life stages of the lion’s mane jellyfish has never been found in the wild, even though researchers understand how it works.

Where do they come from?

You may not have thought about that – until one morning when the bay is suddenly full of them.

This species is found along the entire Norwegian coastline, and it can grow extremely large in northern areas: It's the world's largest jellyfish.

Its tentacles are lined with tiny venomous harpoons, hidden in specialised cells, which can fire into your skin at more than 60 kilometres per hour if you touch them. Read more about this on Science Norway.

But all these jellyfish were once tiny jellyfish larvae, emerging from a polyp – just one of their many life stages.

A polyp is a sea-anemone-like creature that attaches itself to something solid, like a rock, seaweed, a pier, or a shell.

"It looks like a miniature sea anemone, one to two millimetres in size, with tentacles," says Falkenhaug.

It's this polyp, where each one can give rise to a dozen or more baby jellyfish, that researchers cannot find in the wild.

The polyp of the lion's mane jellyfish has been observed in laboratories and in controlled sea experiments, but never found in the wild, says Falkenhaug.

Many jellyfish in the Oslofjord, none on the west coast

At times, jellyfish appear in huge numbers in one area and are absent in another. That's because currents and wind carry them around, sometimes lifting them from deeper waters to the surface, explains Falkenhaug.

There is no systematic counting of jellyfish in Norway, but people across the country report sightings through the site Marine citizen science.

"We got messages from the west coast asking where all the lion's mane jellyfish were this year," says Falkenhaug.

Meanwhile, in some parts of the Oslofjord, jellyfish sotters reported extreme quantitites.

"Some events had to be canceled because swimming wasn't possible," she says.

Could polyps be the key?

Why does the number of jellyfish vary so much from year to year?

Falkenhaug suggests that the polyp stage may hold the answer.

How many jellyfish appear in summer depends largely on how many polyps form and how well they survive the winter.

Certain temperatures may trigger polyps to begin releasing baby jellyfish.

Falkenhaug explains that they can also enter a kind of dormant state, waiting for more favourable conditions, such as more suitable temperatures and better access to food.

This means they may hold back for years before producing jellyfish.

But since researchers don't know exactly where the polyps exist in the ocean, they cannot track their development throughout the year.

Most viewed

"They're colourless and difficult to spot," she says.

Searching without success

Even when researchers have specifically searched for such polyps, they haven't found the lion's mane jellyfish.

A 2021 NTNU study in the Trondheimsfjord examined what jellyfish polyps were present: they found moon jellyfish, but not lion's mane.

And yet, lion's mane jellyfish do exist in the Trondheimsfjord, just as they do along the whole Norwegian coast. The question remains: Where do they come from?

Polyp humour

A Dutch research team asked this very question in 2016 in the article Where are the polyps?

They went searching for polyps' DNA from several different species.

The researchers looked on rocks, piers, wrecks, and many other places, but found only moon jellyfish.

In 2020, they published a follow-up with the playful title Here are the polyps.

But still, no lion's mane polyps were found. Instead, for the first time, researchers identified polyps of the blue jellyfish.

This was revealed by testing the polyps' DNA.

A different species

Scientifically named Cyanea lamarkii, the blue jellyfish belongs to the same genus as the lion's mane jellyfish but is a different species.

It never grows as large as the lion's mane jellyfish.

"It prefers warmer water," says Tone Falkenhaug.

The blue jellyfish thrives further south, but in recent years its numbers may have increased. They have been observed all the way from the Oslofjord to Finnmark – perhaps due to rising winter sea temperatures.

These conditions make life easier for the species’ polyps, which in turn leads to more blue jellyfish during summer.

Falkenhaug has even found their tiny polyps attached to the inside of old mussel shells.

Since the polyps of different jellyfish species look almost identical, DNA testing is usually required to tell them apart, the researcher explains.

"Not surprised they're so hard to find"

"It's exciting that they found polyps of lamarkii," Espen Rekdal tells Science Norway. He is a marine biologist and underwater photographer.

He has filmed and searched for jellyfish of all kinds, both large and small, and he confirms that jellyfish polyps are tricky.

"I'm not surprised they're so hard to find," he says.

Polyps are tiny tufts that often attach beneath or between rocks. They are easy to overlook if you're not specifically looking for them, he says.

Rekdal points out that there are many things in the ocean that are extremely difficult to locate.

"But once you know what to look for, you might eventually figure out how to spot them more easily," he says.

Even the polyps of the moon jellyfish, which are very similar in size and appearance to lion’s mane, can be extremely elusive.

They also hide in unseen and unknown places.

A seabed surprise

In Bergen, a seabed restoration project in recent years brought unexpected results.

Old, polluted seabed was covered with new substrate.

"After that, the entire seabed was bare. Nothing was growing there, not even on the rockes," says Rekdal.

The following year, however, the area experienced a massive bloom of moon jellyfish.

"When we drove our ROV through the swarms of moon jellyfish, all we could hear was flop-flop-flop as they hit the propellers," he says.

It's unclear what caued this, but Rekdal suspects the seabed renewal played a role in the sudden bloom.

"Maybe a predator or competitor hadn’t had time to establish itself," he says.

In any case, there are still many unanswered questions about jellyfish polyps.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

Related content:

Subscribe to our newsletter

The latest news from Science Norway, sent twice a week and completely free.