Have you seen many pictures like this of space?

But when you look up at the sky when the weather is nice, it is all blue.

Why are pictures of space so colourful?

ASK A RESEARCHER: The night sky is pretty black, and on cloudless days it is blue. So why are many pictures of space so colourful?

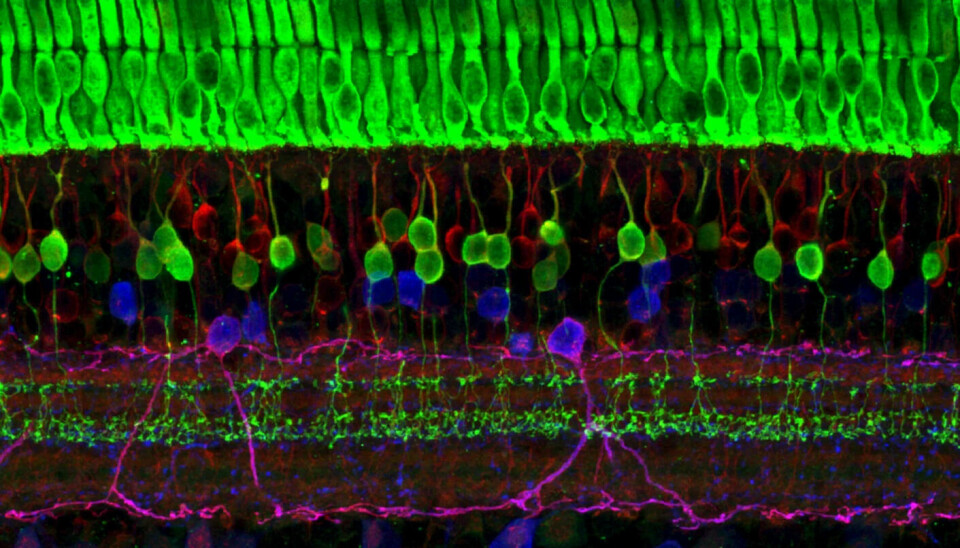

You've probably seen amazing pictures of space.

There are pink stars, red planets, and colourful cosmic dust clouds.

Yet, standing here on Earth looking up, the sky is still blue, and you can’t see any of the colours you see in those amazing space images.

So where are these colours and why don't we see them from Earth?

Why is the sky blue?

Some days the sky is pink, purple, or even yellow. But if we look up on a cloudless day, the sky is blue. And at night, it is dark blue or black, and we can see white stars in the distance.

So why is the sky blue during the day?

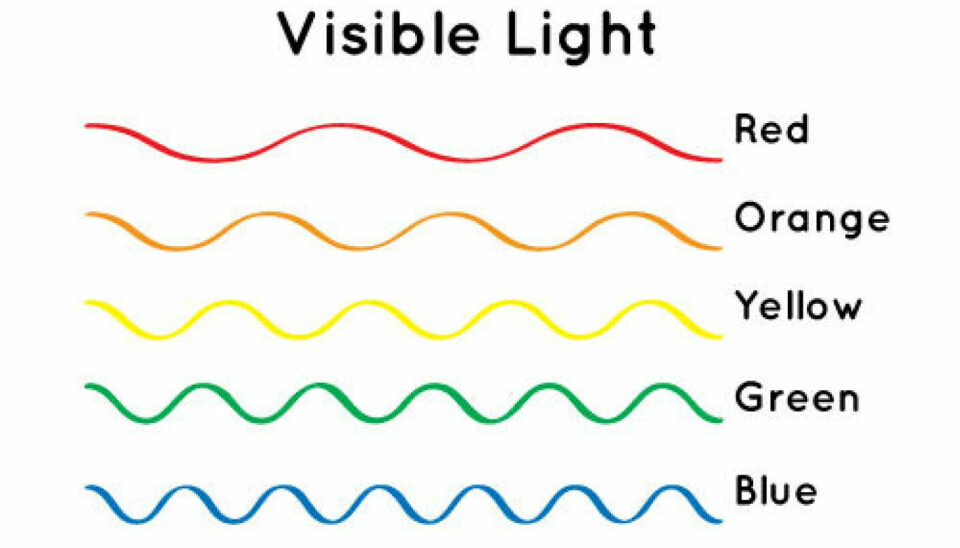

The sun emits white light that shines down on Earth, but the light actually contains all the colours of the rainbow.

The different colours have different wavelengths, meaning they are affected differently by the Earth’s atmosphere.

The air is composed of tiny particles called molecules that affect how the different colours pass through the atmosphere from the sun.

Since blue light has short waves, it is scattered through the air. The other colours have larger waves and can therefore pass by the Earth’s atmosphere.

The blue in sunlight is scattered around the air particles, so when we look up at the sky, it is this scattered blue light we see.

When the sun sets

The sky has colours other than blue when the sun rises and sets.

That is because, as the sun sets, the light comes in at a different angle, passing through a much thicker layer of atmosphere.

This scatters the blue light so much that only the red and yellow light reaches our eyes.

So now we know why the sky is blue (and occasionally pink), but what about all the colourful things out in space? Why don't we see these colours from the ground?

Our eyes need light

Jan-Erik Ovaldsen is an astronomer and runs the website himmelkalenderen.com (Astronomy calendar).

“Why can't we see the colours in space?”

“The explanation is that the human eye has two main types of light-sensitive cells: cones and rods,” Ovaldsen says.

Cones function in daylight, and they are the ones that allow us to see colours.

Rods are much better at detecting light, but they don't detect colours.

“We humans can’t see colours unless what we’re looking at has a certain brightness,” he says.

Telescopes see better than us

“So how do telescopes detect these colours?”

“Telescopes have mirrors that are much larger than our eyes, thus collecting more light,” Ovaldsen says.

Astronomers also use a long exposure time. This means that light is allowed into the camera for many minutes or even several hours, so the light from stars and other things in the universe accumulates.

Ovaldsen says that many pictures of space go through colour filters and are assembled on computers so that we can see as many things as possible.

He also mentions that some pictures are taken with other types of light that we cannot see, like infrared, ultraviolet, or X-ray. These images then have to be ‘translated’ into light that we can perceive.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik.

Read the Norwegian version of this article on ung.forskning.no

Photo 1: NASA / ESA / STScI

Photo 2: umroeng chinnapan / Shutterstock / NTB

------