How Norwegians made sure criminals went to Hell

During the Middle Ages, people were deeply concerned about the fate of bad criminals: Not only was it necessary to punish them on Earth, but every effort had to be made to make certain they went to Hell.

Skulls buried in a half-circle, facing southeast. A decapitated skeleton, with its head buried between its thighs and the feet cut off. Skeletons where the skulls have been removed and heads buried separately, upside down.

These might sound like the ingredients of a Hollywood horror movie, or perhaps a pagan ritual, but they are not. Instead, they are all examples of ways that Norwegian society from 500 years ago tried to guarantee that criminals and other bad people got the punishment they deserved, not only on Earth but also in the eternal afterlife.

All of these examples have been excavated over the last 20 years in Norway from an area southwest of Oslo, in a town called Skien. Archaeologists recognize an area in the town as one of first Christian burial grounds. Later, the same area was a place where criminals were executed.

Unconsecrated ground near the gallows

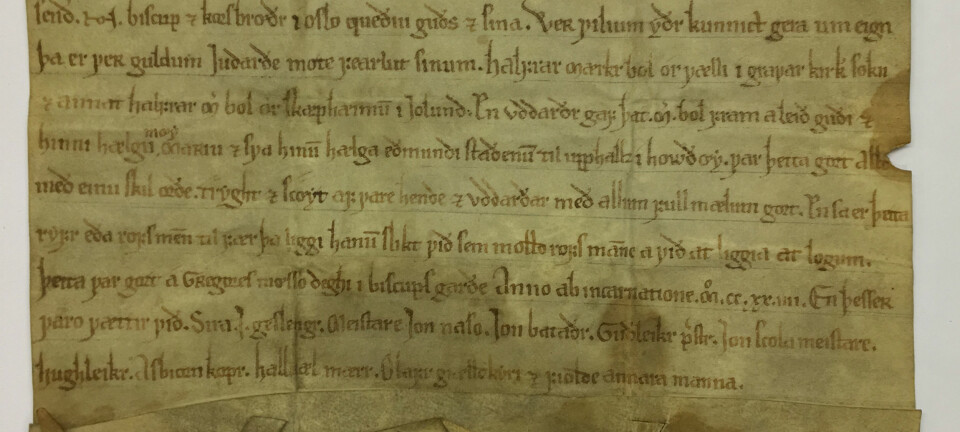

Sometime between 1010 and 1040, Hakastein Church was erected in the area where the skulls were found. The church may have been Norway's first.

The church had a Christian graveyard with consecrated ground until about the year 1400. After then, the Catholic Church deconsecrated the burial place, almost certainly because of the situation in Norway after the Black Death.

The dead person with the skull between the thighs, and other skeletons that had been decapitated with their skulls buried upside down, were buried in this deconsecrated ground around the year 1500. There was also a gallows nearby, as evidenced by the name of a nearby hill, Galgebakken (literally Gallows Hill).

“There is very strong symbolism involved in being buried face down,” said Gaute Reitan, an adviser in Rescue Archaeology from the University of Oslo’s Museum of Cultural History. Reitan was one of the researchers who dug up the decapitated skeletons with the skulls buried face down. “That means you can’t see the sunlight in the eastern sky on the day you rise again. The message is clear: This man should not go to a good place in the hereafter.”

“And if your feet have been chopped off, it probably means that someone wants to guarantee that you don’t come back as a ghost to visit,” he added.

Are dead people really dead?

Today we are quite sure that dead people are dead.

But that was not always the case for people during the Middle Ages and in the centuries afterwards.

The distinction between life and death, body and soul, was not nearly so clear as today. The life you lived on Earth was perceived by most as a short and often brutal prelude to the eternal life you would live in Heaven.

Or in Hell.

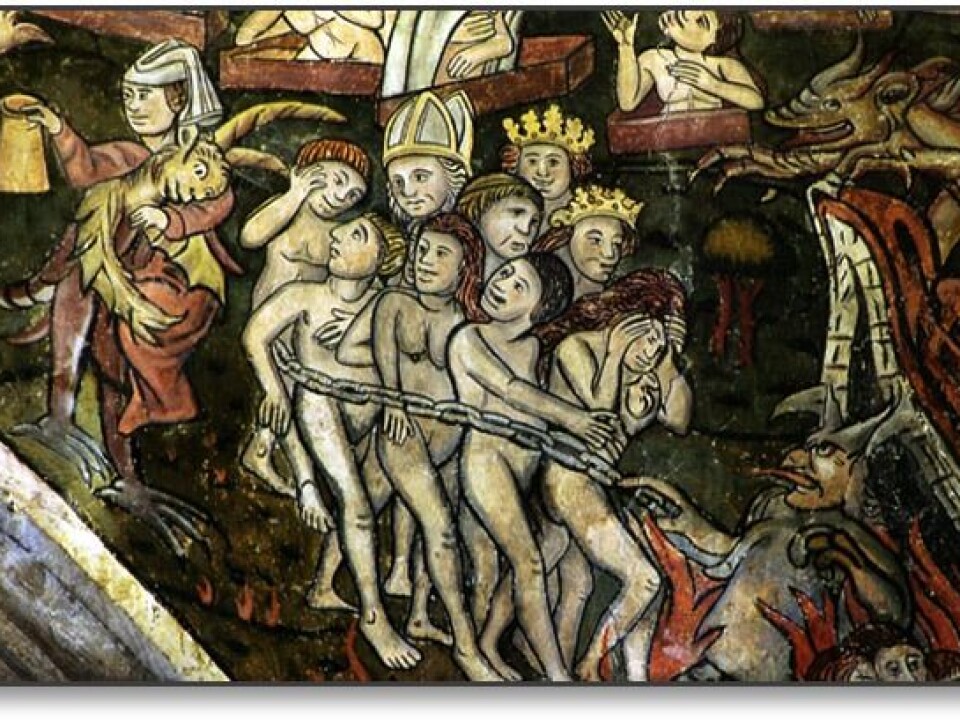

“Heaven and Hell were living realities for people during that period in a way that we can scarcely imagine today,” says Arne Bugge Amundsen, a theologian and cultural historian at the University of Oslo (UiO).

“People knew what both places looked like. Just think of the Christian artwork from the Middle Ages and later,” he said. “No one had any doubt about what it meant if you went to Hell.”

Backing up St. Peter

Not everyone during the Middle Ages was convinced that St. Peter at the Pearly Gates would be able to keep track of who should go to Heaven or Hell.

That meant that society had to come up with a system to back up St. Peter, just to make sure that people who should go to Hell actually went there.

“Where people were buried in Norway was carefully regulated by both laws and regulations, from the early Christian times until well after the Reformation in the 1500s,” Amundsen said. “It was simply not permitted for criminals to be buried in consecrated church land.”

People who committed suicide and unbaptized children were also forbidden from being buried in consecrated ground. This was how society sent a clear message as to where people should spend their time in the hereafter, Amundsen said.

A second punishment

Anne Irene Riisøy is medieval historian at University College of Southeast Norway in Drammen who is also interested in the history of criminals and burials in Norway.

In the Middle Ages, being denied a burial in consecrated ground was seen as a second punishment for a crime, she said.

“It was considered double punishment and something that many people would try to avoid,” she says.

Riisøy believes that the threat of being buried in unconsecrated ground might have had a deterrent effect on potential criminals at that time. It might have also had a deterrent effect on potential suicides, she said.

What happened after the Reformation?

Amundsen, the cultural historian from the University of Oslo, has recently looked at what happened to dead criminals after Norway went from being Catholic to Protestant in the early 1500s. At first, not much changed.

For example, he describes a funeral from 1578 that was overseen by Jørgen Eriksen, who was superintendent for the Lutheran Church at the time. A superintendent was the Lutheran equivalent of a Catholic bishop. Eriksen made it clear in the funeral that “wicked people” will not be buried with “God's chosen children”, but in a place where they can be eaten by birds and animals.

But in the year 1604, the authorities issued a clarification on burials that Amundsen thinks more clearly reflects what Protestant Norway thought about issues related to Heaven and Hell.

The clarification states that cemeteries will be available to "any honest man."

And in keeping with Martin Luther's thoughts that faith is the only way to salvation, the clarification emphasizes that a place in the cemetery did not in itself guarantee salvation.

But that also meant that being buried outside the cemetery was no longer a guarantee to the contrary.

-------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no