Ukraine war: The world will never be the same, says professor

Many people are quietly hoping that things will get back to normal, once Russia's war in Ukraine ends. It won't, says professor Janne Haaland Matlary.

When the war in Ukraine ends, the country can be rebuilt, refugees can return home, Europe will be at peace again and the world can go on.

Or maybe not?

“In Norway, it might seem as if everything will be like it was before,” says Janne Haaland Matlary.

The war will end, and the West can resume its relationship with Russia and China.

“We’re quietly hoping that everything will get back to normal,” she says.

And by ‘normal,’ she means the way things were during the long period of peace after 1990.

“I think this is a very natural attitude, but it may also be dangerously naive,” she says.

Total disregard for UN Charter

Matlary is a professor of political science at the University of Oslo and at the Norwegian Defence Staff College, with international politics as her field of specialty.

She has now written a book about the Ukraine war and what it portends for world peace, democracy and Norway.

In her book Verden blir aldri den samme - ‘The world will never be the same. An everyday life of political security' - Matlary addresses why the world will not be the same as before the war and what our new everyday life might be like.

“There are two things that are particularly important when we talk about the world not being the same,” says Matlary, who was also State Secretary in Norway’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs from 1997 to 2000.

“First, both Russia and China have shown their total disregard for our norms here in the West,” she says.

‘All nations are equal’

According to Matlary, the main norm in international politics is the idea of sovereignty – that all nations are independent and equal.

It also means that the residents of a country have fundamental rights, that these human rights apply to everyone and that the government of each country must protect them.

“This war is not only about security policy, but also about the UN Charter,” says Matlary.

“Of course, China says that they uphold all human rights, but many examples abound where freedom of expression and assembly are not allowed there.

Russia wants war

Russia's intentions and what they are actually willing to do are the other reason why the world won’t be the same.

Russia has shown that it not only is able to go to war, it also wants to, according to Matlary.

She calls the current war a war of aggression. Russia used it first against Crimea and now in the attack on Ukraine.

“People often talk about Russia and China rearming, but do they actually have the capacity to do what they threaten to do? The answer is yes,” says Matlary.

“Russia also has the intention – and the willingness – to use force,” she says.

“And precisely the last point is absolutely key.”

Why Finland reacted so strongly

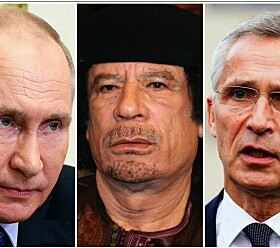

Matlary recounts Putin's meeting with his own security council two days before the attack on 24 February last year. Television images from the meeting show all members of the Security Council standing up and saying that they recognize Luhansk and Donetsk as independent states.

Putin’s actions strongly violate our norms in the West, according to Matlary.

“You can’t recognize part of another country as a separate state. Although Russia did the same thing in Georgia in 2008,” she says.

That’s when Finland understood that Russia is running roughshod over the way we do things here in Europe and the West in general, says Matlary.

“And it was then that Finland, which has maintained a realistic and balanced position for decades, understood that it was now too dangerous to remain outside NATO.”

“For me, this is a very solid indicator of how serious the countries that know Russia well perceive the situation to be,” she says.

War for no reason

One of the things that Matlary finds startling about this war is that Russia – for no particular reason – has chosen to invade a neighbouring country.

“There’ve been no wars before this where a country has used military force without stating a reason for it. Countries that have attacked have at least used – or tried to find – a reason under international law. In this case, there was just nothing,” says Matlary.

“So this war has shocked, if not the whole world, then at least the West.”

Nevertheless, Matlary believes that people in Norway aren’t shocked enough. She writes in her book that neither politicians nor the Norwegian people understand the seriousness of the war in Ukraine and what it could mean for Norway.

“When the Finns, who have long relied on realpolitik, take the step and rush – practically throwing themselves – into NATO, then Norway should recognize the seriousness of the war,” she says.

The Swedes did like the Finns and reacted quickly, applying for membership without the usual democratic processes.

Indecisive Norwegian politicians

Norway didn't have to take any measures, strictly speaking, because it is already a NATO member, Matlary explains.

She therefore believes that the war is not as much in the forefront of Norwegian consciousness as in its neighbouring countries.

“Nevertheless, our politicians are very indecisive,” she says.

She believes this also becomes clear when looking at Norwegian media coverage.

“The war in Ukraine is quickly turning into just one issue among many others, even though it’s in the news every day.”

She points to the report that the Norwegian Defence Commission launched earlier this month, which concluded that the situation is also serious for Norway.

“Despite a serious deterioration in the security situation in recent years, the Norwegian public has only to a limited extent recognized the need for a strong and forward-looking defence,” said the commission's chair, Knut Storberget, when he handed over the report to the Minister of Defence on 3 May.

The Commission recommended a NOK 30 billion increase to what was proposed in the state budget and that an additional NOK 40 billion should be added per year in extra rearmament allocations for a ten-year period.

“The report was in the media for a day, then it was forgotten,” says Matlary.

Knowing when matters are serious

Matlary believes that what she describes as politicians' indecisiveness has to do with the way governance in Norway is organised, with directorates and ministries that have specific areas of responsibility.

Where exactly does the responsibility lie to prevent Norway from ending up in a war with Russia?

“We have a sector principle that is extremely well incorporated into our governing system and good to have during normal times,” says Matlary.

“But when there’s an external challenge that has consequences for the whole of society, this system has no quick and effective coordination,” she says.

For a domestic threat, like drone flights or the cutting of communication cables, the Norwegian Ministry of Justice and Public Security is responsible.

“Threats from abroad are the responsibility of the Ministry of Defence. And if they’re a mixture of the two, then they might be the responsibility of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs,” says Matlary.

“We have no national security council. The British, the French, the Finns and the Americans all do.”

The fact that all our ministries have to be coordinated means that matters take time and that responsibility is spread out, according to Matlary.

“The management of it all means that no one says, ‘Now matters are serious, and this is important’.”

She reminds us that Norway has 197.7 kilometres of border with Russia.

“The fact that a large conventional state-on-state war is taking place in our back yard makes it particularly dangerous and risky for Europe,” she says.

Ability to act quickly

“When hybrid attacks occur concurrently with sabotage and possible military grey zone incidents, for example, a state needs the ability to coordinate all information extremely quickly into a unified situational picture and to respond with unified measures,” says Matlary.

That is why countries like the UK and Finland have national security councils under the prime minister's office, consisting of the most important politicians at the top that include the sectors concerned, officers and experts.

Matlary says that a modern attack would consist of several elements, such as cyberattacks on the state, media and defence, sabotage of infrastructure and possible military actions.

“The aim is to exploit the element of surprise and create confusion, chaos and fear. Then an attack has a higher chance of success,” she says.

Matlary believes that both a country’s leaders and its people need to be prepared for something like this to happen.

“For the authorities, being able to assess the situation quickly with input from all affected sectors and come up with a counterattack is crucial.”

“In that kind of situation there’s no time to discuss which ministry ‘owns’ the problem,” she says.

Ongoing assessments in the Ministry

Sciencenorway.no first contacted the Ministry of Defence for a comment on Matlary's critique. They referred us to the Ministry of Justice and Public Security, which was unable to respond within three days.

We then returned to the Ministry of Defence, which replied:

‘At the moment, the Ministry of Defence does not wish to comment on the contents of the book, given that much of it goes to the core of ongoing assessments around the Defence Commission's report. The question of establishing a national security council was raised by the Defence Commission when they presented their report at the beginning of May. The report from the Defence Commission will be included as one of several bases for the work on the new long-term plan for the Armed Forces, which will be laid out in 2024. This plan will also include the Security Professional Council of the Norwegian National Security Authority (NSM), the Chief of Defence's Professional Military Council and the report from the Total Preparedness Commission.’

Practise making decisions

Matlary illustrates the need for multi-pronged assessment with the example of the subsea communication cable to Svalbard that was destroyed last year. The internet connection disappeared for several days, and the police investigated the breach as possible sabotage. But the case was dropped.

“The investigators should have immediately found out if there actually was sabotage and if other strange occurrences happened up there – in other words, gather the picture of the situation from many sectors,” she says.

Norway practises for certain individual incidents for which it has established procedures. One example is what is called ‘renegade’, when a passenger plane is hijacked and is going to crash in a Norwegian city.

“Making the decision whether or not to shoot down the plane is practised. It’s a terribly difficult decision to make and therefore it needs to be practised,” says Matlary.

“Of course, information is extremely important in such a situation. Is this a suicide bomber or a prankster? You have just a few minutes to decide. These types of situations can be defined in advance, and concrete guidelines can be drawn up for decisions that have to be made. But if a lot is going on at once, without clarity as to what is actually happening, you need to be able to quickly gather information and decision-makers from several sectors,” says Matlary.

Future is uncertain

Matlary wants to be clear about the consequences of the war so people understand how serious it is. That is why she uses strong words and images, both in her book and in her interview for this article.

But is the situation as serious as she says and writes about?

Helene Sjursen is a researcher at the Centre for European Studies at the University of Oslo. We ask her the same question as we posed to Matlary: What will the world look like after the war in Ukraine?

“We know very little about that,” says Sjursen.

“We don’t know how long the war will last, we don’t know what the outcome will be, and we don’t know what direction Russia’s political development will take.”

This uncertainty is exactly what characterizes the situation we’re in now, she believes.

But Sjursen is clear about one thing:

“There must be legal accountability,” she says.

“This war is an obvious violation of international law. Russia has attacked another state and that is illegal,” says Sjursen.

She mentions other violations of international humanitarian law as well, such as attacks on civilians, torture and the kidnapping of children.

Why NATO is getting involved

“The violations of international law are what have led to NATO supporting Ukraine and going to such great lengths to supply weapons,” says Sjursen.

She points in particular to Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg's speech about NATO's involvement in the war.

“NATO and the EU's support for Ukraine is justified with reference to violations of international law. The war is illegal. Once the war is over, those who have committed these violations must be held accountable,” says Sjursen.

“A court settlement will also confirm that international politics has some basic rules of the road that cannot simply be broken. In this sense, such a proceeding will be able to contribute to re-establishing or strengthening international law.

Only once accountability has been achieved will we see what kind of world we live in.

———

Translated by: Ingrid P. Nuse

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

------