Infants have to learn a fear of heights

Our wariness of heights is not ingrained, but it develops quickly as toddlers use their vision to start moving about.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Parents will cringe in memory of a terrifying situation:

Their pride and joy has recently learned to move about by his or herself. The kid crawls toward some drop or slope − the edge of a bed or maybe even a staircase. The kid reaches the edge and undauntedly continues into the abyss. It’s a heart-stopper for a mum or dad.

Luckily this phase doesn’t last long. But why aren’t we simply born with a fear of heights? When does this very rational fear emerge?

To find out, researchers at the University of California, Berkeley – including the Norwegian doctoral student Audun Dahl – taught toddlers to drive a little battery-powered wagon.

The result showed that the child doesn’t have a fear of heights until he or she learns that their interaction with the world is a two-way street − the world can pack a wallop.

Awareness needed to trigger fear

Research has shown that a wariness of heights appears pretty soon after a baby learns to crawl, but not immediately. As in the proverb “a burnt child dreads the fire”, it’s natural to think tots learn to fear heights by taking a tumble or two.

But scientists found out back in the 1960s that there was no clear link between how much a small child falls and how uncomfortable he or she is on the edge of a drop.

Dahl and his colleagues at Berkeley’s Infant Studies Center have another theory: They think the wariness links to the child’s vision and how it evolves after learning to crawl.

“It’s not until the child learns to move around on its own that it learns to use visual information from the environment to perceive and control their own movements,” says Dahl.

And the more you see that your immediate environment can affect you, the more you can fear it.

Children used to moving around gain more wariness

Dahl and colleagues tested their theory by equipping tots who hadn’t yet learned to crawl with small motorized wagons. These children were just a little over seven months old on average. But they learned how to steer the wagons and they could drive around on their own.

No such carts and driving experience was given to a control group of tots their age.

“The wagons provided a way of giving children locomotor experience in an experimental setting, so it was incidental who were the ones who could move about who were the ones who couldn’t. This was a way of excluding factors that could have an effect on the result, for instance biological maturation,” says Dahl.

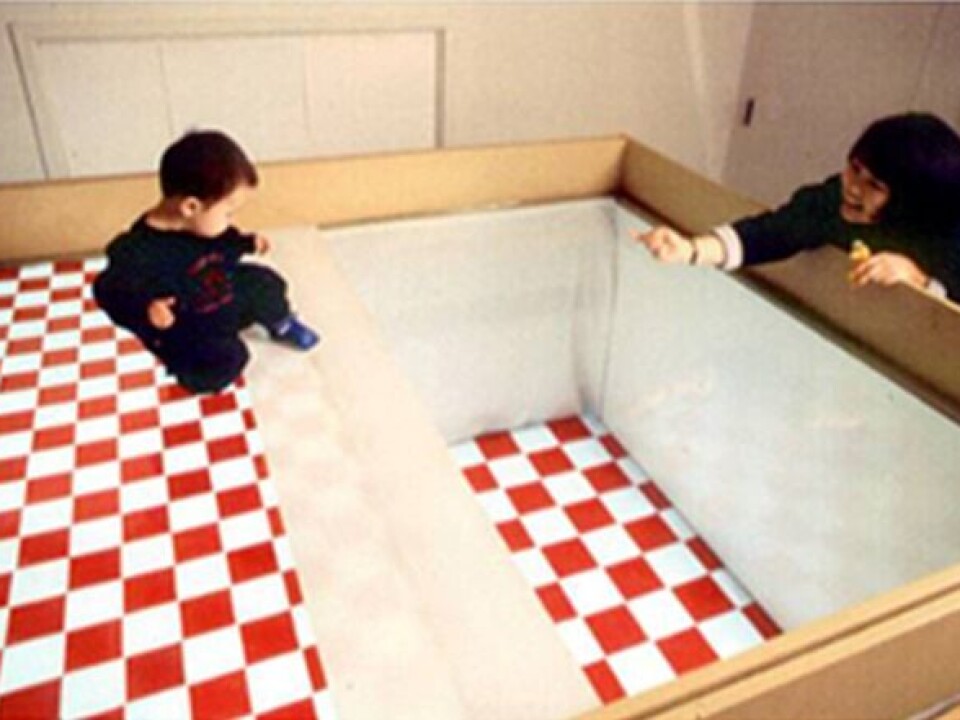

After three weeks the children were put to a decisive and potentially scary test, a visual cliff:

They were lowered down toward what either looked like a floor just a little below them, or a comparable floor made to look as if it were over a metre below. Dahl and colleagues monitored their pulses as this was done.

The infants who had rode around on the electric wagons the last weeks were more afraid of the height – their heart rates increased noticeably – than the infants who had no experience with locomotion.

Extra test with train illusion

The researchers tested whether the reactions really related to visual perception in another test in the same study. This time, infants who had learned to crawl were placed in a room made with an illusion of the walls suddenly moving back or forth.

The illusion was like when your train is stopped at a station and you think your train has started to move, but it’s actually the train on the track next to yours that has been set in motion.

The children who reacted the most to the sudden movements, by taking a step back or forth to compensate, were also those who had the highest heart rates when being lowered above a drop.

A lag in learning allows for exploration

Together the two tests showed that children who are most tuned into the world about them, and how it affects their own movements, are the ones who are most weary of heights.

“When a child looks down into a drop, for instance the apparent edge of a visual cliff, much of the visual information they are accustomed to using disappears,” explains Dahl.

“This is the experience which acts as the genesis for the wariness of heights.”

But one question remains, write the researchers: Why is it that infants don’t acquire a fear of heights as soon as they learn to crawl?

There’s a lag of a few weeks before this fear takes hold, and this interval is nerve-wracking period for parents and can be painful for kids.

The researchers attribute this to the way we learn to know the world. If we had been afraid from the very start it could hamper our impulse to explore our environment. That too is a vital impulse, for instance enabling us to learn the difference between slightly risky heights and really treacherous heights.

The old adage “no risk, no reward” also applies to small children. Parents have to try not to be overprotective while continuing be vigilant − and keep their infant explorers out of real harm’s way.

--------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling