Ketamine: Why can't severely depressed patients access this effective treatment?

Several studies have shown that psychedelics can work to treat depression. So why does the government refuse to offer this treatment to patients who need it?

Depression is one of the leading causes of diminished quality of life. Between six and twelve per cent of all people in Norway have depression at any given time.

It can also be fatal. In Norway, about 650 people take their own lives every year. Many of them are severely depressed.

Current treatment not good enough

Today, we use treatment methods that are not good enough, according to many professionals in the field.

For decades, treatment for depression has mostly involved talk therapy and antidepressants. Both require long-term treatment of the patient.

Talk therapy often takes several months to work, if at all. It takes weeks and sometimes months for anti-depressant medication to take effect, if it has any effect.

One in three patients with depression is not helped by the treatment methods offered today.

With the depression come problems coping with everyday life, low self-esteem and a lack of interest in much of what brings joy in life.

Paradigm shift

Treating depression might now be approaching a paradigm shift, as suggested by the article title ‘Psychiatry goes psychedelic’ in the research journal Nature in December 2021.

Since then, even more studies are showing that psychedelics can work to alleviate depressive disorders and suicidal thoughts.

The psychedelic drug ketamine is leading the way.

The drug has been used as an anaesthetic in surgery since the 1970s. Around the year 2000, some researchers discovered by chance that administering a low dose of ketamine produced large and rapid effects on depression in many patients. The dose needs to be small enough so the patient does not fall asleep from it.

Works quickly

Evidence is growing that ketamine has an effect on depression by stopping negative thought patterns. Most studies show about a 50 per cent reduction in depressive thoughts.

A recent American study showed that ketamine worked better than electroshock therapy on patients with depression. After three weeks of treatment, 55 per cent of the patients who had received ketamine experienced positive effects – compared to about 41 per cent of patients who had electroshock therapy.

The drug also works quickly, unlike other forms of treatment.

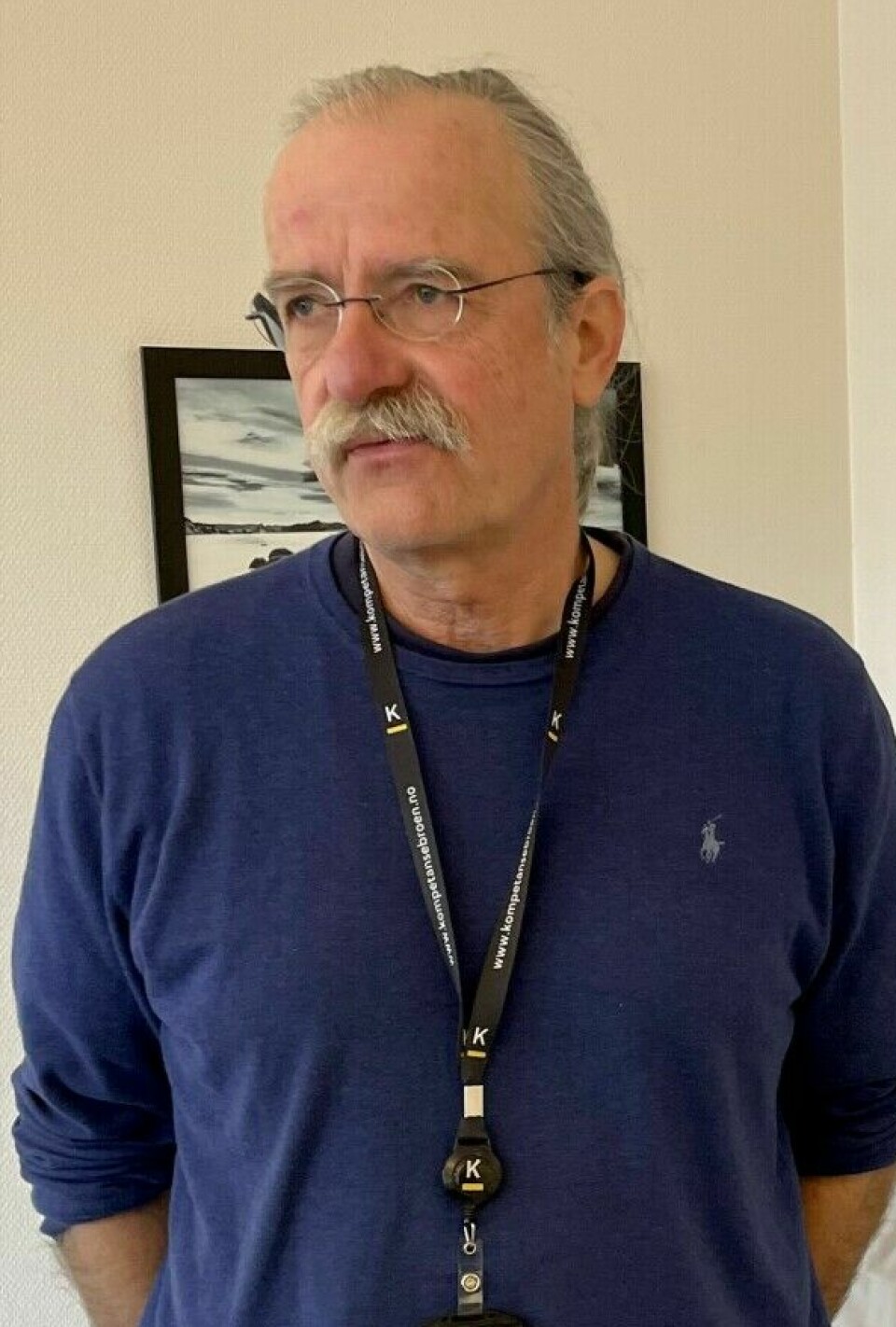

“It’s fascinating that you can treat people who’ve been depressed for several months, and then they get better within a short time,” says Ole A. Andreassen. He is a professor and neuroscientist at the University of Oslo.

Ketamine is not a dangerous drug, says Andreassen.

“It’s used in thousands of operations every day. But in that case you become completely unconscious. We administer a lower dose so that patients stay awake. This way the drug affects thinking and reduces negative thought patterns that keep the depressive state going. A short-term effect of a low dose of ketamine can be enough to initiate positive processes that help patients to get rid of the depression.”

Andreassen believes that ketamine could have the potential to change our understanding of the mechanisms of mental disorders.

First public hospital

Ingmar Clausen is a psychiatrist and department head at Østfold Hospital. His team treated the first patient with ketamine in a public hospital in Norway in November 2020.

The treatment in Østfold takes place at a small district psychiatric outpatient clinic in Moss municipality. There, the therapists use the ketamine "off label," meaning outside its approved area of use. They are the only public hospital in Norway to use ketamine in this way.

The drug is used in conjunction with talk therapy.

Authorities want to wait

Several studies have shown good efficacy of ketamine in treating depression. Nevertheless, the Norwegian health authorities want to know more before they consider approving the drug for treatment.

They argue that effectiveness and safety have not been well enough documented. The health authorities are waiting for more and better studies.

The Norwegian Institute of Public Health (FHI) has had the task of reviewing all available and current ketamine research from around the world.

Clausen says that abundant documentation is available that suggests this treatment is something that can be taken forward. “But because some studies have not yet been completed, the health authorities are postponing their decision. That’s a bit difficult to accept,” he says.

Patients from all over the country

Clausen argues that given a substance that works so effectively, it should be used on very sick patients with a high risk of suicide.

This point is currently under discussion, says Clausen.

The District Psychiatric Centre (DPS) at Østfold Hospital accepts patients with severe depression from all over the country.

But the centre now has a waiting period of many months for patients with treatment-resistant depression and acute risk of suicide, says Clausen.

He believes a national problem has been left to a small clinic to deal with.

Placebos are a problem

Andreassen, the brain researcher at the University of Oslo, believes the large number of patients who would like to receive this treatment can create problems for research.

One problem for researchers who want to find out more about the effects of ketamine is being able to determine what is a placebo effect and what is a real effect.

The placebo effect is a well-known human phenomenon that can sometimes help people recover from illness. It is difficult to separate the placebo effect from a direct effect of the treatment. Many alternative treatment methods may primarily have a placebo effect.

This phenomenon is not easy to research.

Can become missionaries

Good medical studies on the effects of drugs should be conducted as ‘blind’ studies.

Doing a blind study means that neither the patient nor the person measuring the effectiveness of the drug knows who is getting the real medicine and who is receiving a placebo that looks identical.

This is particularly difficult to achieve with a psychedelic drug, because the patients usually know whether they are receiving real medicine or a placebo, says Andreassen.

Another problem is that patients who want to join this study do not tend to be sceptical. Many people are convinced that they can recover from depression right away.

“And we – the researchers running the studies – are positive too and thus motivated to find an effect. We can easily become missionaries who want to prove that this drug is effective. That’s why it’s important to carry out solid scientific studies,” says Andreassen.

He believes it is fundamentally critical for the authorities to enforce having placebo controls for all research into new medicines.

Studies are underway

Although the acute effectiveness of ketamine in treating depression has been shown in many studies, uncertainty is still present.

Andreassen believes researchers need to conduct randomized studies and use placebos to investigate the duration of a trial drug’s effect and the risk of side effects.

Several studies have therefore now been initiated to map the efficacy and side effects of ketamine in Norway.

"But should health authorities say that people shouldn’t use ketamine, because the research isn’t good enough?" Andreassen asks. “Is it right for the healthcare system to prevent patients from receiving ketamine when most people experience positive and quick results?"

At the very least, the authorities should support clinical studies, Andreassen says.

Private companies take over treatment

The professor at the University of Oslo admits that he and his colleagues in this field face a dilemma.

The situation is not made any easier by the fact that private players in the Norwegian health market have launched themselves into ketamine treatment on a large scale.

In Oslo today you can choose between several private clinics. Anyone can give you an injection of ketamine – for a price. Most clinics charge between NOK 4000 and 5000 per treatment, roughly between 370-460 USD, not including before and after consultations.

According to Østfold Hospital, some patients need several treatments to achieve optimal effectiveness. If the desired result is achieved, four to six further treatments are carried out over a period of two to three weeks. The treatment can then be maintained.

At Østfold Hospital, patients only have to pay the deductible for outpatient consultation, says Clausen.

“I usually jokingly say that a treatment with us costs NOK 39.50 (just under 4 USD),” he says.

———