Ocean acidification puts Norway in a pickle

Research since the last IPPC climate change report has provided further proof of mounting acidification of the oceans. Norwegian experts think the fifth IPPC assessment report, to be released in Stockholm this week, should be an eye-opener.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Debates about carbon emissions and the consequences for human life don’t usually encompass direct ways that Norwegians will be affected.

Rising sea levels that will engulf the coasts of Bangladesh, the disappearance of South Pacific islands and more extreme hurricanes in the Gulf of Mexico are good reasons to curb carbon emissions, but they don’t radically change the lives of Scandinavians, at least short-term.

But since the UN’s 2007 climate report was issued, research has reinforced our understanding of ocean acidification, a problem that has immeasurable momentum. It also can undermine Norway’s seafood industry.

Ocean acidification is especially bad for marine organisms that make shells out of calcium carbonate. Among these are numerous types of plankton, prawns, lobsters, snails, mussels, starfish, sea urchins and corals.

Acidification occurs when ocean water (and freshwater lakes) absorb atmospheric carbon dioxide, some of which reacts with water to form carbonic acid.

The result is that the ocean’s pH, although still basic rather than acidic, is getting lower, or more acidic. Cold water absorbs more CO2 than warm water, and freshwater from melting ice can curtail the ocean’s ability to neutralize this acidification.

This means that ocean acidification has particularly strong consequences for cold coastal countries like Norway.

Potential problem

“Clearly, ocean acidification is a problem for a nation that is heavily involved in fisheries. Verifiable research now shows that the ocean’s pH value has changed, and this makes the polar areas the most vulnerable,” says Eystein Jansen of the Bjerknes Centre for Climate Reseach, one of the main authors of the new climate report to be issued on Friday.

According to the Norwegian Environment Agency, the surface of the ocean has become an average of 30 percent more acidic worldwide in the past 200 years.

In July this year the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere reached a record-breaking 400 ppm (parts per million) at the Norwegian Institute for Air Research’s station on Svalbard. Even if the Earth’s mean temperature has not increased in the past 10-15 years, carbon dioxide levels continue to mount, and the oceans are being acidified.

Not insignificant

Jansen calls ocean acidification the greenhouse effect’s evil twin. No matter what we do to mitigate the effect of emissions, ocean acidification will continue as long as we emit carbon dioxide.

“If a new report is much clearer and assertive with regard to the sea, and also on the impacts on Norway, Norwegian politicians will have to take this much more seriously than earlier assessments,” says Arne Johan Vetlesen of the University of Oslo.

He is a philosopher and avid climate debater and author who writes about environmental issues.

Vetlesen points out that Norwegians drive cars the most and use collective transport the least in comparison with other European countries. Norwegians are also near the top of the list worldwide when it comes to vacation air travel.

“I think politicians have to face the music. But to date we’ve had some sort of artificial lag or delay in public discourse on Norwegians’ consumption as part of the problem. We are not a role model. On the contrary we could serve as a warning, a bad example.”

Scallops in acidified waters

Sissel Andersen of the Institute of Marine Research has just completed a study of what happens to scallops when the pH of the sea drops. Her findings will be published this autumn.

Scallop larvae are important food for zooplankton, which in turn are eaten by fish. The shells are also important because they bind carbon in the sea.

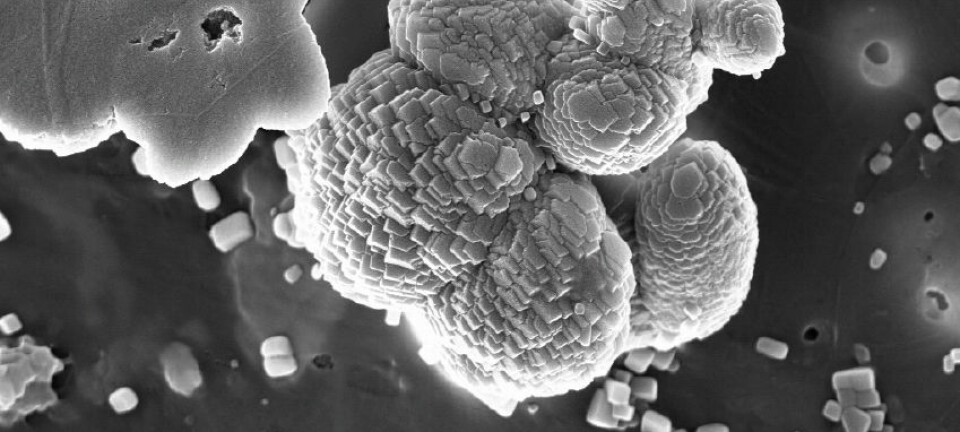

In her experiments scientists fertilized scallops and released their tiny larvae in tubs of water with varying degrees of alkalinity to see whether this had an effect on them in their first days of life. This is when their shells are most vulnerable to lower pH values.

The tiny larvae create a thin shell within just a few days, making them look like microscopic scallops.

These thin shells are composed of calcium carbonate and scientists checked to see if the lower pH values in the seawater caused shell deformations or lower survival rates.

The pH level of normal seawater in Norway can now be as low as 7.98. The researchers filled a tub with seawater with a pH of 7.7, which is what they think we can expect in the ocean in 100 years if we keep emitting CO2 like we do today.

The larvae in pH 7.7 seawater were less likely to survive and likelier to have shell deformities than the scallop larvae in the control group, which were raised in water with a pH of 7.98.

“The results show that acidification has a big impact on survivability and growth. This is typical for many types of ocean larvae,” says Andersen.

Doesn’t affect fish directly

Other researchers at the Institute of Marine Research have conducted similar studies of cod larvae, but these studies showed that variations in pH of the water had no impact on survivability.

Even though fish might not be directly impacted, changes in the food chain can be perilous, according to marine biologist Jan Helge Fosså of the Institute of Marine Research.

“Species react very differently to changes in pH values. This can transform the competition between species. In other words, new species could take a dominant position in the food chain. New food chains can be started. But there’s no way to predict the outcome.”

Important management

Fosså says that previous research shows that changes in environmental conditions and overfishing are a recipe for causing fish stocks to collapse.

“The best advice is to manage our fish stocks as well as we can. We cannot fish out local stocks and we should try to promote as much genetic variation as possible. Maybe the species can adapt, but we don’t know which groups in a stock have the best chances of adaption and survival.”

He says that even though Norway ranks high internationally with regard to fisheries management, much hinges upon EU countries doing their jobs in the North Sea and continued smooth cooperation with Russia in the Barents Sea.

--------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling