Researchers are learning more about the mysteries of brain cancer

Brain cancer is one of the most serious types of cancer a person can develop. It is also extremely difficult to study. This has limited advances in treatment for some time. Now, however, there’s a little more reason for optimism, according to one researcher and a patient.

When Pål Oraug had a seizure while running on a treadmill in March 2019, he first thought he had epilepsy. He was sent for an MRI.

On the way home the phone rang. He was told to return to the hospital.

"You've got a brain tumour," they said.

This was just a few weeks after he had run a personal best at the New York Marathon. He finished 95th among all men who ran.

“I thought I was as healthy as a horse,” he told the chairman of the Norwegian Brain Tumour Association at a meeting in Oslo in mid-February.

In reality, he had a 4.5 centimetre brain tumour in his head.

Norway and Iceland at the top

“Brain cancer strikes people at random,” says Rolf Bjerkvig, a professor at Haukeland University Hospital and one of Norway’s foremost experts on brain cancer.

We know very little about what causes this cancer, he says.

“One of the strongest theories is that you are born with a property that is found in the brain. But we still don't know what this property is,” he said.

Norway and Iceland are the top countries when it comes to the occurrence of this type of cancer.

“I think that is because we have a better healthcare system and that we are better at diagnosing it,” Bjerkvig said.

Networks help

Bjerkvig is head of a network of Norwegian researchers that work across universities and disciplines on brain cancer.

Together, they are making a concerted effort to improve treatment for the 500-600 people who develop brain cancer in Norway each year.

Many of these cancer patients are children. Brain cancer is the most common form of cancer in children, and the most frequent cause of cancer death in children.

In addition to people whose cancer originates in the brain, there are between 3,000 and 3,500 patients who die from what are called brain metastases. These are cancer cells that have spread from other parts of the body and entered the brain. In the end, the cancer in the brain is what causes the patient’s death.

Very deadly

Bjerkvig himself has been associated with the Luxembourg Institute of Health for 15 years, where he has been involved in developing a completely new technology. This approach could be decisive in developing better treatment for this very deadly cancer.

The average survival time for the most serious tumour type, glioblastoma, is only 14 to 15 months. But there are many other forms of brain cancer, and many people live much longer than that.

While great progress has been made in the treatment of many different types of cancer in recent years, there have been very few advances in brain cancer.

“We have gained a lot of knowledge about the biological properties of these cancer tumours in the last ten years. But since the beginning of the millennium, no significant progress has been made in treatment,” Bjerkvig said.

The brain is hard to reach

There are several reasons for this lack of progress, he says.

Delivering drugs to the brain is very complicated. The brain is protected by a blood-brain barrier that prevents unwanted substances in the blood from entering the brain.

Unfortunately, it also prevents medicine from entering the brain.

Another important reason is that each tumour’s cancer cells have different genetic characteristics.

This makes it extremely complicated to determine which treatment should be given to the patient. The tumours are far too complex.

“Each patient has a cancer tumour that is unique to them. If you treat the cancer, only a few patients respond,” Bjerkvig says.

This means that targeted therapy, which has become quite successful in treating other forms of cancer, does not work for this cancer.

It’s also difficult to surgically treat brain tumours. Even when the tumour is removed, it leaves behind cancer cells that then invade the brain.

Cultivating mini brains

The technology that Bjerkvig has helped to build is based on this last problem.

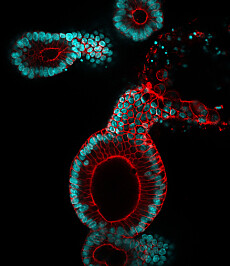

It’s simply not possible to open up a patient's head to study the brain. Researchers have therefore grown mini brains in the laboratory. They do this by using immature brain cells from rat foetuses.

But they also need a tumour.

The researchers can use pieces from a biopsy of a cancerous tumour in a patient to develop a small microtumour. When they put the tumour pieces in the mini brain, they can study how the cancer cells invade the brain tissue.

Can also treat the tumour

This type of model also allows them to treat the tumour. This approach is being pursued by a number of researchers now.

A researcher can make a ton of microtumours from a biopsy. They can then screen the various tumours against many different types of drugs. This approach allows them to figure out which drugs work.

“This way we can determine which treatment we should give the patient,” Bjerkvig said.

Norway has the money

This technology exists today.

In addition to the centre in Luxembourg, Germany is now building a centre that can use this technology.

But Bjerkvig says Norway should also invest in this technology. The network he is head of now is working to get funding to set one up in Norway.

The equipment is estimated to cost between NOK 50 and 60 million, according to the Norwegian Cancer Society.

“I just don’t understand why Norway, with all the money we have on the books, cannot get this equipment in place. This is not an investment that will cause inflation,” Bjerkvig said.

Stable for now

Like most others who are affected by brain cancer, Pål Oraug was given the standard treatment of two operations, radiation and chemotherapy.

The treatments reduced the size of the tumour. It lies there, encapsulated, and is stable.

After the diagnosis, he has continued to run and focus on the positives in life. He has learned to enjoy each day, he says.

He is now also chairman of the Norwegian Brain Tumour Association.

The association organized the meeting in Oslo in mid-February which brought together researchers, politicians and bureaucrats for a debate on how we can achieve better treatment.

Optimism in the air

Oraug believes that the spirit of the meeting was optimistic.

“There was great agreement that we must make progress,” he said.

But getting the technological equipment to the hospitals takes too long, he believes.

Much of the challenge also lies in getting hospitals to use the equipment, he said. Norwegian hospitals need people to operate the equipment and analyse the samples.

According to Oraug Norway doesn’t spend enough money on cancer research overall, considering how many people are affected.

Greater cooperation between the public and private sectors is very important for society to make progress, Oraug said.

Brain cancer is considered a rare disease, but there are many different tumour variants.

“Large pharmaceutical companies tend to focus on the more common types of cancer that affect many people. It’s difficult to get the industry alone to find a miracle cure for what is perhaps the most demanding cancer of all – brain cancer,” he said.

Cooperation is important

The Norwegian Cancer Society has allocated NOK 15 million to establish the national expert group for brain cancer research, which Rolf Bjerkvig leads.

“This network has allowed us to bring different professions together to work on the same problem. We are a small country, so it’s important that we collaborate across disciplines,” said Ole Alexander Opdalshei at the Oslo gathering. Opdalshei is assistant general secretary of the Norwegian Cancer Society.

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

------