How the brain connects words and smells

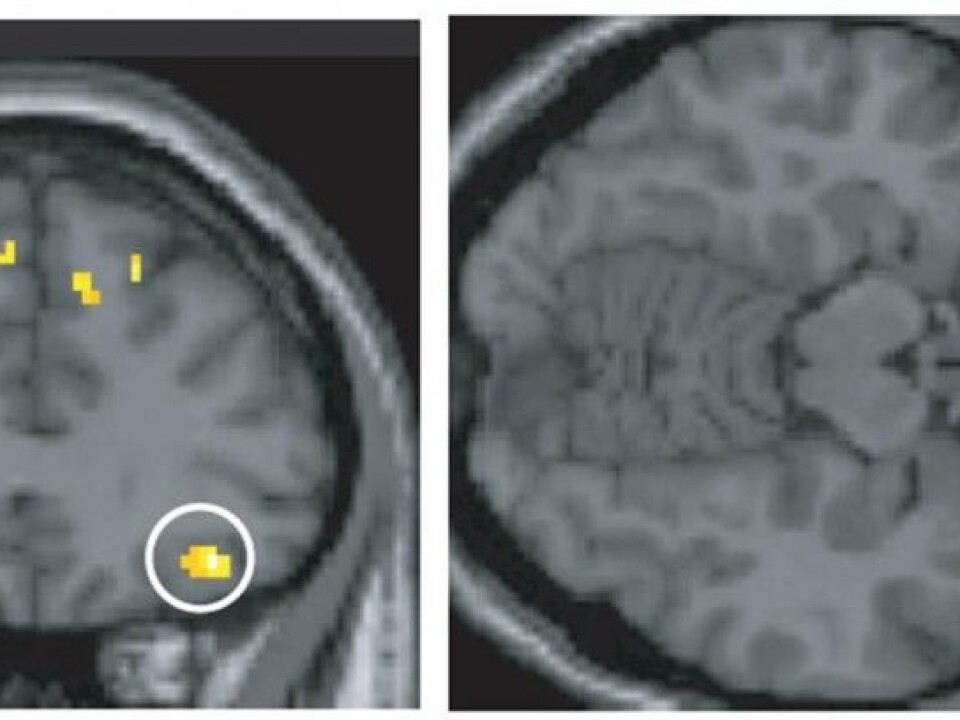

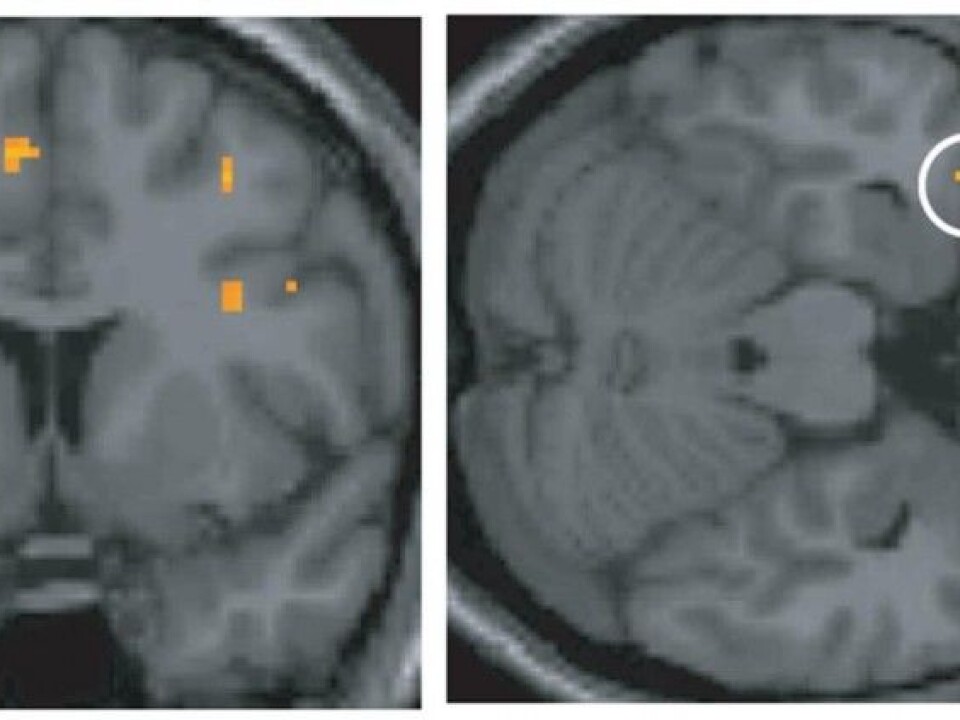

Scientists have discovered the parts of the brain that are used to recognize smells. With new imaging technology, scientists can observe activity in the brain.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

We can easily describe sensations from the eyes, ears, and mouth. But the sense of smell is different, and even ordinary smells like banana or coconut can be difficult to describe and identify.

In a new study, researchers examined the relationship between language and smell.

They captured images of the brains of people who tried to associate words with either smells or images. It turned out that the two tasks activated completely different areas.

“These findings can help us understand why it is so difficult to detect smells,” says Jonas Olofsson, a researcher in psychology at Stockholm University.

First words, then smell

Participants were presented with either an image or a smell, then a word that sometimes matched the sensory impression, sometimes not.

The study subjects spent more time and made more errors when the task involved odours.

Previous research has shown that when we are presented with a picture (e.g. a rose), followed by a word (e.g. “lemon”), the language part of our brain is activated.

In this study, the researchers have shown that different areas of the brain are activated when smells are involved in the task.

Researchers know that people have greater difficulty describing odours than visual impressions, for example, but this is the first time it has been demonstrated that different areas of the brains are activated.

The findings are published in the Journal of Neuroscience; the researchers believe that they may be useful in the development of scent tests for dementia.

Why smell is so difficult

There are many theories about why it is so difficult for us humans to describe smells. One theory is that the sense of smell is evolutionarily very old and perhaps not adapted to the social way of life that developed later.

“It is the more recently developed part of the human brain that is adapted to our social lives,” says Lasse Pihlstrøm, a physician and researcher in neurology at the Oslo University Hospital in Norway.

“We communicate with gestures and sounds, but we cannot communicate with smells in the same way.”

Another theory is that the language area of the brain has easier access to information from our eyes. This information has been processed through several levels in the brain, which makes it easier for us to put words to it.

“Information about smells is not processed in the same way and is quickly passed on,” Pihlstrøm explains.

Pihlstrøm explains that visual impressions are built from basic components such as colours, contrasts and lines, while smells seem to be monolithic perceptions.

“However, some researchers have argued that humans can identify one trillion unique smells,” he says.

Tribal societies

Some peoples are much better at describing smells than others. The Jahai, a tribal society on the border between Thailand and Malaysia, excel at this task.

It can be critical to be able to recognize a smell in the rainforests in this area and describe it to others. Poisonous and edible plants may resemble each other visually but smell different.

Researchers have found that the Jahai give very advanced olfactory descriptions, with concepts that accurately designate different parts of smells.

Pihlstrøm recounts an experiment done earlier this year by researchers from the Universities of Nijmegen and Lund, where descriptions of colours and smells of Jahai and Americans were compared.

When the American subjects were presented smells like cinnamon, chocolate or onions, the descriptions were long, imprecise and inconsistent. Participants from the Jahai tribe, however, characterized the scents in a precise, abstract way, which varied little from person to person, even though many of the smells were unknown to them.

“Jahai seem to be able to isolate the basic features of odour as easily as we see colours,” Pihlstrøm explains.

Smelling practice

But how is this possible? And what comes first, words or sensations?

According to Pihlstrøm, the sense of smell may have a central place in Jahai culture, where the connection between words and olfactory input is practiced from an early age.

“Perhaps they are simply exploiting a potential we are all born with, since smells are more important to them in their daily lives,” says Pihlstrøm.

Testing for Alzheimer’s?

The ability to recognize odours is impaired in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease.

The researchers behind the study in Stockholm believes that it can be used in diagnosis.

“Now that we know more about the areas of the brain that are used to recognize smells, we can make better tests for those who are at risk for dementia,” says Jonas Olofsson.

Lasse Pihlstrøm is more sceptical: “It can’t be ruled out, but there are many other possible reasons for a poor sense of smell.”

“I think this study is mostly interesting because it teaches us something fundamental about the interplay between perception and language in healthy people,” he says.

----------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Lars Nygaard