A big salmon blow-up

New microscope technology can portray your dinner fish in a new light, through a mix of biology, handicraft – and art.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

“This is a handicraft, not research,” says Jacob Torgersen.

He’s a researcher at Nofima Marin in Ås, outside of Oslo, and his daily work involves taking pictures of infinitesimal bits of salmon and other fish. These can be cells, proteins, fat tissue and any other parts.

This can help researchers understand what’s going on inside the fish.

For instance, it can help them ascertain what makes fish grow faster or taste better.

A toolbox

Torgersen and his colleagues at this Norwegian food research institute are problem solvers attempting to find out how to see various changes in the fish.

“Microscopes enable us to get inside a fish and see what kind of cells it has, what they do, and relevantly how they change if we alter their conditions,” he says.

Torgersen, who’s actually a molecular biologist, says he sometimes feels like more of a craftsman.

“All sorts of problems are presented to us, so I have to know which tools in my toolbox can be used for any given question,” he explains.

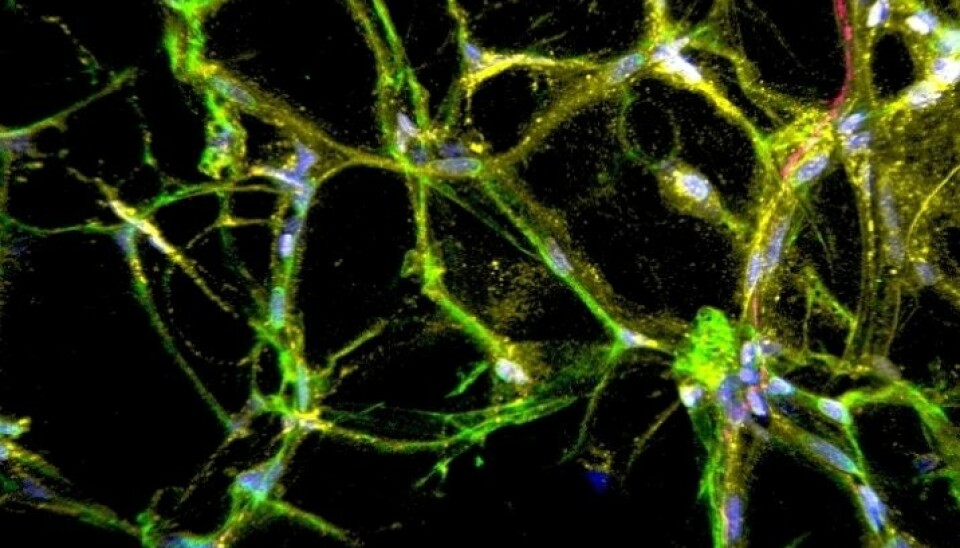

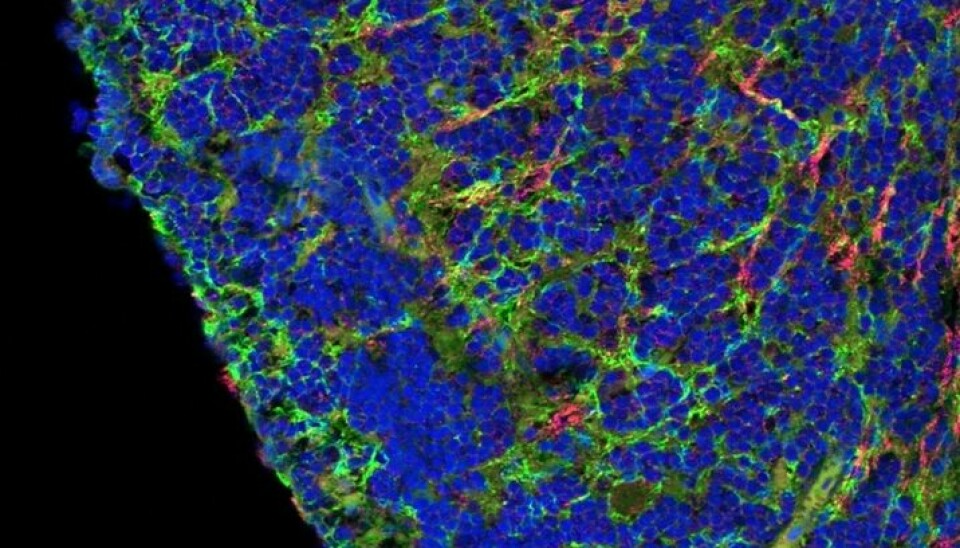

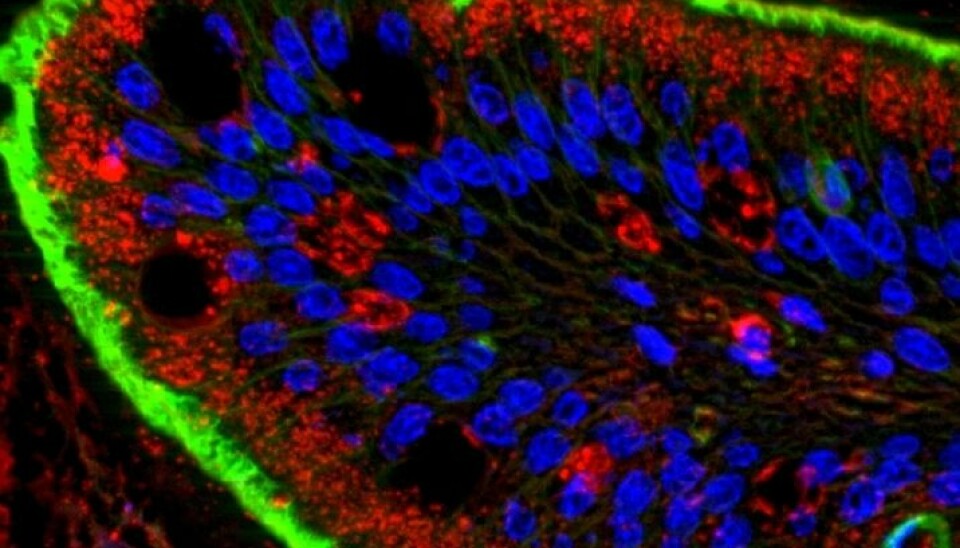

If you look closer at a salmon, it isn’t easy to discern between one bit of cell and another. A solution is to colour the different parts with separate hues.

“Tissue isn’t homogenous. It consists of all kinds of different cells and varieties of tissue,” he says.

“How do I tint just this one type of cell so it, and only it, turns pink? What’s the best technique for revealing the connection between this protein and the blood cells around it? These are the sort of quandaries I deal with.”

Mournful mitochondria

A fish intestine is caught by the camera.

“The food passes by, then it goes into the nook, where it is absorbed and transported inwards.”

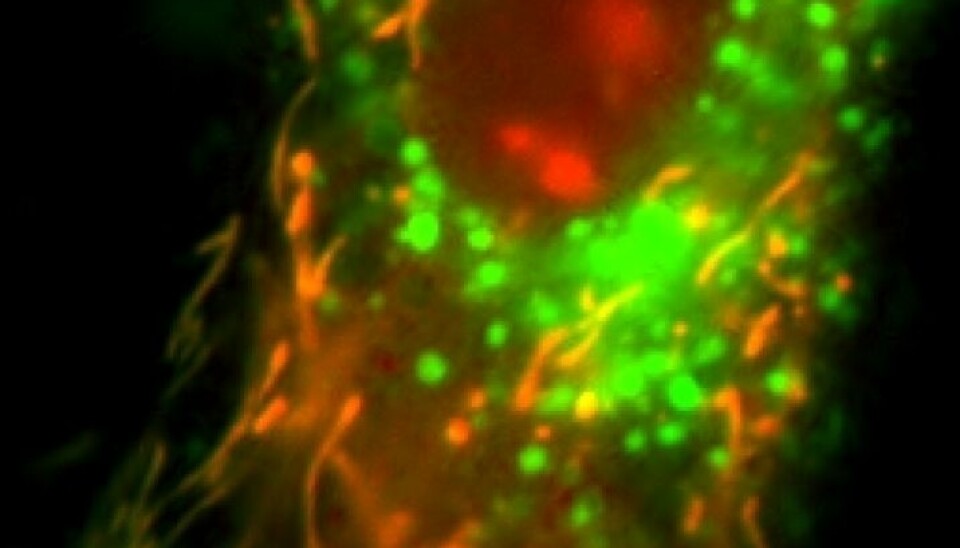

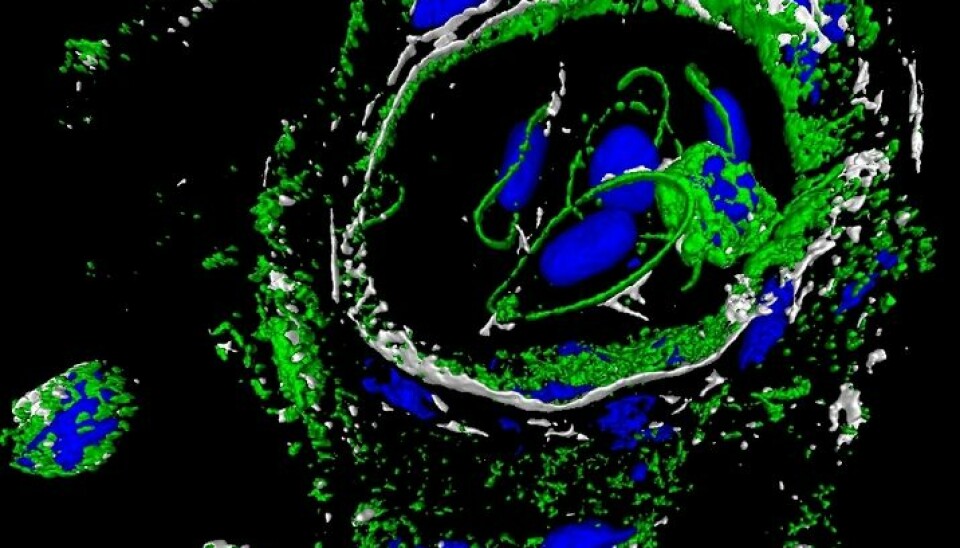

Another of Torgersen’s images shows a sick mitochondrion, an infirm version of one of the cell’s power plants, where the energy the cell needs to survive comes from the food the salmon eats. A salmon mitochondrion should be round and compact but these have become elongated, almost like spaghetti.

“Salmon in Norway are nearly vegetarians because the feed they're given consists mainly of plant fatty acids. We’ve coloured the mitochondria in the cells here and then given them plant fatty acids to see how it affects the quality and health of the fish,” he says.

“When they stretch out like this it’s an indication that the cell isn’t quite happy.

“This is fun; it’s biology and a skilled craft and to some extent it’s also art,” says the researcher.

—————————————————

Read this article in Norwegian at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling